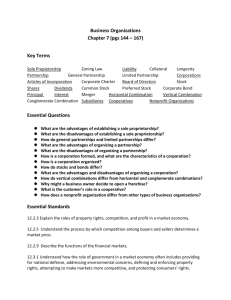

Exploring Reasons Fo..

advertisement