Gas Laws and Stoichiometry: Chemistry Presentation

advertisement

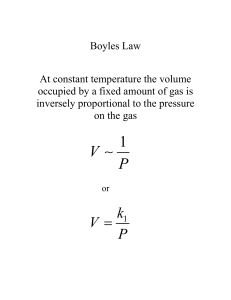

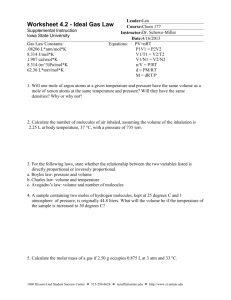

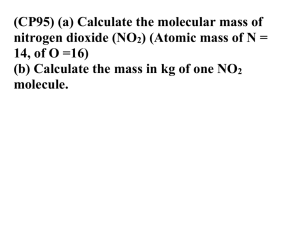

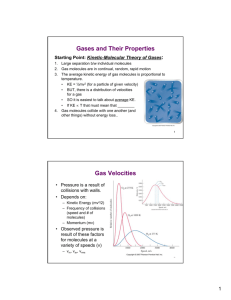

Chapter 8 Gases The Gas Laws of Boyle, Charles and Avogadro The Ideal Gas Law Gas Stoichiometry Dalton’s Laws of Partial Pressure The Kinetic Molecular Theory of Gases Effusion and Diffusion Collisions of Gas Particles with the Container Walls Intermolecular Collisions Real Gases Chemistry in the Atmosphere States of Matter Solid Liquid Gas We start with gases because they are simpler than the others. 3/11/2016 2 Pressure (force/area, Pa=N/m2): A pressure of 101.325 kPa is need to raise the column of Hg 76 cm (760 mm). “standard pressure” 760 mm Hg = 760 torr = 1 atm = 101.325 kPa Boyle’s Law P1V1 = P2V2 V x P = const (fixed T,n) 1662 Charles’ Law V / T = const (fixed P,n) 1787 Avogadro 1811 V1 / V2 = T1 / T2 V / n = const n = number of moles (fixed P,T) Boyle’s Law: Pressure and Volume The product of the pressure and volume, PV, of a sample of gas is a constant at a constant temperature: PV = k = Constant (fixed T,n) Boyle’s Law: The Effect of Pressure on Gas Volume Example The cylinder of a bicycle pump has a volume of 1131 cm3 and is filled with air at a pressure of 1.02 atm. The outlet valve is sealed shut, and the pump handle is pushed down until the volume of the air is 517 cm3. The temperature of the air trapped inside does not change. Compute the pressure inside the pump. Charles’ Law: T vs V At constant pressure, the volume of a sample of gas is a linear function of its temperature. V = bT T(°C) =273°C[(V/Vo)] When V=0, 273°C T=- Charles’ Law: T vs V The Absolute Temperature Scale V = Vo ( t 1+ 273.15oC ) Kelvin temperature scale T (Kelvin) = 273.15 + t (Celsius) Gas volume is proportional to Temp Charles’ Law: The Effect of Temperature on Gas Volume V vs T V1 / V2 = T1 / T2 (at a fixed pressure and for a fixed amount of gas) Avogadro’s law (1811) V = an n= number of moles of gas a = proportionality constant For a gas at constant temperature and pressure the volume is directly proportional to the number of moles of gas. Boyle’s Law V = kP Charles’ Law -1 V = bT P1V1 = P2V2 (at a fixed temperature) V1 / V2 = T1 / T2 (at a fixed pressure) Avogadro V = an (at a fixed pressure and temperature) n = number of moles V= -1 nRTP PV = nRT ideal gas law an empirical law Example At some point during its ascent, a sealed weather balloon initially filled with helium at a fixed volume of 1.0 x 104 L at 1.00 atm and 30oC reaches an altitude at which the temperature is -10oC yet the volume is unchanged. Calculate the pressure at that altitude . P1V1 P2V2 n1T1 n2T2 n1 = n2 V1 = V2 P1 P2 T1 T2 P2 = P1T2/T1 = (1 atm)(263K)/(303K) STP (Standard Temperature and Pressure) For 1 mole of a perfect gas at O°C (273K) (i.e., 32.0 g of O2; 28.0 g N2; 2.02 g H2) nRT = 22.4 L atm = PV At 1 atm, V = 22.4 L STP = standard temperature and pressure = 273 K (0o C) and 1 atm The Ideal Gas Law PV = nRT What is R, universal gas constant? the R is independent of the particular gas studied PV (1atm)(22.414L) R nT (1.00 mol)(273.15 K) R 0.082057 L atm mol K -1 -1 (101.325 x 103 N m-2 ) (22.414 x 10-3 m3 ) R (1.00 mol) (273.15K) 1 R 8.3145 N m mol K 1 R 8.3145 J mol K 1 1 PV = nRT ideal gas law constants R 0.082057 L atm mol K -1 1 R 8.3145 J mol K 1 -1 Example What mass of Hydrogen gas is needed to fill a weather balloon to a volume of 10,000 L, 1.00 atm and 30 ̊ C? 1) Use PV = nRT; n=PV/RT. 2) Find the number of moles. 3) Use the atomic weight to find the mass. Example What mass of Hydrogen gas is needed to fill a weather balloon to a volume of 10,000 L, 1.00 atm and 30 ̊ C? n = PV/RT = (1 atm) (10,000 L) (293 K)-1 (0.082 L atm mol-1 K-1)-1 = 416 mol (416 mol)(1.0 g mol-1) = 416 g Gas Stoichiometry Use volumes to determine stoichiometry. The volume of a gas is easier to measure than the mass. Gas Density and Molar Mass PV nRT m PV RT M Rearrange m P M V RT m P d M V RT Gas Density and Molar Mass Example Calculate the density of gaseous hydrogen at a pressure of 1.32 atm and a temperature of -45oC. Example Fluorocarbons are compounds containing fluorine and carbon. A 45.6 g sample of a gaseous fluorocarbon contains 7.94 g of carbon and 37.7 g of fluorine and occupies 7.40 L at STP (P = 1.00 atm and T = 273 K). Determine the molecular weight of the fluorocarbon and give its molecular formula. Example Fluorocarbons are compounds of fluorine and carbon. A 45.60 g sample of a gaseous fluorocarbon contains 7.94 g of carbon and 37.66 g of fluorine and occupies 7.40 L at STP (P = 1.00 atm and T = 273.15 K). Determine the approximate molar mass of the fluorocarbon and give its molecular formula. RT M d P m d V 1 1 45.60g 0.082 L atm mol K x 273K 1atm 7.40L M 138 g mol 1 1mol C 0.661 mol C 0.661 mol 1 part C n C 7.94 g C x 12 g C 1mol F 1.982 mol F 0.661 mol 3 parts F n F 37.66 g F x 19 g F Mixtures of Gases Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressures The total pressure of a mixture of gases equals the sum of the partial pressures of the individual gases. n 3 RT n1RT n 2 RT P1 , P2 , P3 V V V RT Ptotal P1 P2 P3 n1 n 2 n 3 V RT Ptotal n Total V Mole Fractions and Partial Pressures The mole fraction of a component in a mixture is define as the number of moles of the components that are in the mixture divided by the total number of moles present. Mole Fraction of A X A nA nA XA n tot n A n B ... n N PA V n A RT Ptot V n tot RT divide equations PA X A Ptot PA V n A RT PA nA nA or or PA Ptot Ptot V n tot RT Ptot n tot n tot Example A solid hydrocarbon is burned in air in a closed container, producing a mixture of gases having a total pressure of 3.34 atm. Analysis of the mixture shows it to contain 0.340 g of water vapor, 0.792 g of carbon dioxide, 0.288 g of oxygen, 3.790 g of nitrogen, and no other gases. Calculate the mole fraction and partial pressure of carbon dioxide in this mixture. n tot n H 2O n CO 2 n O 2 n N 2 0.34 0.792 0.288 3.790 n tot 0.1809 18 44 32 28 n CO 2 0.018 X CO2 0.0995 n tot 0.1809 PCO 2 X CO 2 Ptot 0.0995 x 3.34 atm 0.332 atm 2NH4ClO4 (s) → N2(g) + Cl2 (g) + 2O2 (g) + 4 H2 (g) The Kinetic Molecular Theory of Gases • The Ideal Gas Law is an empirical relationship based on experimental observations. – Boyle, Charles and Avogadro. • Kinetic Molecular Theory is a simple model that attempts to explain the behavior of gases. The Kinetic Molecular Theory of Gases 1. A pure gas consists of a large number of identical molecules separated by distances that are large compared with their size. The volumes of the individual particles can be assumed to be negligible (zero). 2. The molecules of a gas are constantly moving in random directions with a distribution of speeds. The collisions of the particles with the walls of the container are the cause of the pressure exerted by the gas. 3. The molecules of a gas exert no forces on one another except during collisions, so that between collisions they move in straight lines with constant velocities. The gases are assumed to neither attract or repel each other. The collisions of the molecules with each other and with the walls of the container are elastic; no energy is lost during a collision. 4. The average kinetic energy of a collection of gas particles is assumed to be directly proportional to the Kelvin temperature of the gas. Pressure and Molecular Motion Pressure (impulse per collision) x (frequency of collisions with the walls) • frequency of collisions speed of molecules (u) • impulse per collision momentum (m × u) • frequency of collisions number of molecules per unit volume (N/V) P (m × u) × [(N/V) × u] Pressure and Molecular Motion P (m × u) × [(N/V) × u] PV Nmu2 Correction: The molecules have a distribution of speeds. PV Nmu2 Mean-square speed of all molecules = u2 Pressure and Molecular Motion PV Nmu2 Make some substitutions 1. 1/2m u2 = kinetic energy (KEave) of one molecule. 2. KE is proportional to T (KEave= RT) 3. Divide by 3 (3 dimensions) 4. N = nNa (molecules = moles x molecules/mole) The Kinetic Molecular Theory of Gases PV 2 = RT = (KE)ave 3 n or 3 (KE)ave = RT 2 3RT u M 2 Speed Distribution Temperature is a measure of the average kinetic energy of gas molecules. Velocity Distributions Distribution of Molecular Speeds 3RT u M 2 u rms 3RT u M 2 8RT uavg πM ump 2RT M ump : uavg : urms = 1.000 : 1.128: 1.225 Example At a certain speed, the root-mean-square-speed of the molecules of hydrogen in a sample of gas is 1055 ms-1. Compute the root-mean square speed of molecules of oxygen at the same temperature. Strategy 1. Find T for the H2 gas with a urms O2 u rms = 1055 ms-1 u M T H2 rms 2 H2 3R 2. Find urms of O2 at the same temperature u Orms2 u 2H2 M H2 3R 3R M O2 u Orms2 H2 about 4 times velocity of O2 u O2 rms 3RT M O2 u 2H2 M H2 M O2 (1005) 2 (2) 264.8ms 1 32 Gaseous Diffusion and Effusion Diffusion: mixing of Gases e.g., NH3 and HCl Effusion: rate of passage of a gas through a tiny orifice in a chamber. 3RT Rate of Eff A u Arms B Rate of Eff B u rms 3RT MA 3RT MB MB enrichment factor MA u rms u 2 M Example A gas mixture contains equal numbers of molecules of N2 and SF6. A small portion of it is passed through a gaseous diffusion apparatus. Calculate how many molecules of N2 are present in the product of gas for every 100 molecules of SF6. MB enrichment factor MA Effussion of N 2 32 (6 x 19) 2.28 Effusion of SF6 2 x 14 # molecules of N 2 X 2.28 = = # molecules of SF6 100 molecules SF6 X = 228 molecules of N 2 Real Gases • Ideal Gas behavior is generally conditions of low pressure and high temperature PV = nRT PV = 1.0 nRT Real Gases • Kinetic Molecular Theory model – assumed no interactions between gas particles and – no volume for the gas particles • 1873 Johannes van der Waals – Correction for attractive forces in gases (and liquids) – Correction for volume of the molecules Pcorrected Vcorrected = nRT The Person Behind the Science Johannes van der Waals (1837-1923) Highlights – 1873 first to realize the necessity of taking into account the volumes of molecules and – intermolecular forces (now generally called "van der Waals forces") in establishing the relationship between the pressure, volume and temperature of gases and liquids. Moments in a Life – 1910 awarded Nobel Prize in Physics PV nRT n 2 Pobs a (V ) V nRT nRT • Significant Figures – Zeros that follow the last non-zero digit sometimes are counted. – E.g., for 700 g, the zeros may or not be significant. – They may present solely to position the decimal point – But also may be intended to convey the precision of the measurement. – The uncertainty in the measurement is on the order of +/- 1 g or +/- 10g or perhaps +/- 100 g – It is impossible to tell which without further information. – If you need 2 sig figs and want to write “40” use either • Four zero decimal point “40.” or • “4.0 x 10+1” The Person Behind the Science Lord Kelvin (William Thomson) 1824-1907 “When you can measure what you are speaking about and express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, you knowledge is of a meager and unsatisfactory kind; it may be the beginning of knowledge but you have scarcely, in your thoughts advanced to the stage of science, whatever the matter may be.” Lecture to the Institution of Civil Engineers, 3 May 1883 The Person Behind the Science Evangelista Torricelli (1608-1647) Highlights – In 1641, moved to Florence to assist the astronomer Galileo. – Designed first barometer – It was Galileo that suggested Evangelista Torricelli use mercury in his vacuum experiments. – Torricelli filled a four-foot long glass tube with mercury and inverted the tube into a dish. Moments in a Life – Succeed Galileo as professor of mathematics in the University of Pisa. – Asteroid (7437) Torricelli named in his honor Barometer P=gxd xh