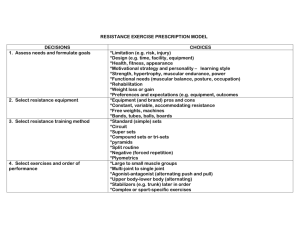

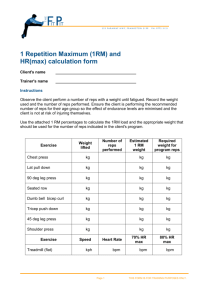

summer strength training

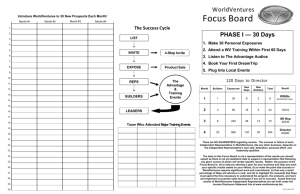

advertisement