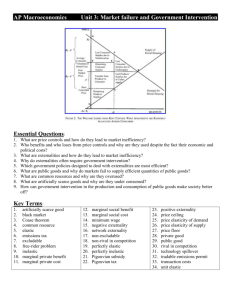

Externalities - AP Microeconomics

advertisement

Private and Public Goods, Externalities, and Taxes AP Microeconomics Module 5 Dannie McKee, July 2013 Private Goods—and Others • What’s the difference between installing a new bathroom in a house and building a municipal sewage system? • What’s the difference between growing wheat and fishing in the open ocean? • In each case there is a basic difference in the characteristics of the goods involved. Bathroom appliances and wheat have the characteristics needed to allow markets to work efficiently; sewage systems and fish in the sea do not. • Let’s look at these crucial characteristics and why they matter… Characteristics of Goods • Goods can be classified according to two attributes: – whether they are excludable – whether they are rival in consumption • A good is excludable if the supplier of that good can prevent people who do not pay from consuming it. • A good is rival in consumption if the same unit of the good cannot be consumed by more than one person at the same time. Characteristics of Goods • A good that is both excludable and rival in consumption is a private good. • When a good is nonexcludable, the supplier cannot prevent consumption by people who do not pay for it. • A good is nonrival in consumption if more than one person can consume the same unit of the good at the same time. Characteristics of Goods There are four types of goods: – Private goods, which are excludable and rival in consumption, like wheat – Public goods, which are nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption, like a public sewer system – Common resources, which are nonexcludable but rival in consumption, like clean water in a river – Artificially scarce goods, which are excludable but nonrival in consumption, like pay-per-view movies on cable TV Characteristics of Goods Rival in consumption Private goods Excludable Nonexcludable Nonrival in consumption Artificially scarce goods • Wheat • Pay-per-view movies • Bathroom fixtures • Computer software Common resources Public goods • Clean water • Public sanitation • Biodiversity • National defense There are four types of goods. The type of a good depends on (1) whether or not it is excludable—whether a producer can prevent someone from consuming it; and (2) whether or not it is rival in consumption—whether it is impossible for the same unit of a good to be consumed by more than one person at the same time. Why Markets Can Supply Only Private Goods Efficiently • Goods that are both excludable and rival in consumption are private goods. • Private goods can be efficiently produced and consumed in a competitive market. • Goods that are nonexcludable suffer from the free-rider problem: individuals have no incentive to pay for their own consumption and instead will take a “free ride” on anyone who does pay. • When goods are nonrival in consumption, the efficient price for consumption is zero. • If a positive price is charged to compensate producers for the cost of production, the result is inefficiently low consumption. Public Goods • A public good is the exact opposite of a private good: it is a good that is both nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption. • Here are some other examples of public goods: – Disease prevention: When doctors act to stamp out the beginnings of an epidemic before it can spread, they protect people around the world. – National defense: A strong military protects all citizens. – Scientific research: More knowledge benefits everyone. Providing Public Goods • Because most forms of public good provision by the private sector have serious defects, they must be provided by the government and paid for with taxes. • The marginal social benefit of an additional unit of a public good is equal to the sum of each consumer’s individual marginal benefit from that unit. • At the efficient quantity, the marginal social benefit equals the marginal cost. • The following graph illustrates the efficient provision of a public good… A Public Good (a) Ted’s Individual Marginal Benefit Curve Marginal benefit 25 $25 18 18 12 12 7 3 1 0 7 MBT 1 3 4 5 6 Quantity of street cleansings (per month) (b) Alice’s Individual Marginal Benefit Curve 3 1 2 Marginal benefit 21 $21 17 17 13 13 9 9 5 MB 5 A 1 1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Quantity of street cleansings (per month) Panel (a) shows Ted’s individual marginal benefit curve of street cleanings per month, MBT, and panel (b) shows Alice’s individual marginal benefit curve, MBA. A Public Good Marginal benefit, marginal cost (c) The Marginal Social Benefit Curve $46 35 46 21 35 17 25 16 0 25 13 25 18 8 6 2 The marginal social benefit curve of a public good equals the vertical sum of individual marginal benefit curves 12 16 MSB 9 8 7 5 3 1 2 3 4 Efficient quantity of the public good MC=$6 2 1 1 5 6 Quantity of street cleansings (per month) Panel (c) shows the marginal social benefit of the public good, equal to the sum of the individual marginal benefits to all consumers (in this case, Ted and Alice). The marginal social benefit curve, MSB, is the vertical sum of the individual marginal benefit curves MBT and MBA. At a constant marginal cost of $6, there should be 5 street cleanings per month, because the marginal social benefit of going from 4 to 5 cleanings is $8 ($3 for Ted plus $5 for Alice), but the marginal social benefit of going from 5 to 6 cleanings is only $2. Providing Public Goods • No individual has an incentive to pay for providing the efficient quantity of a public good because each individual’s marginal benefit is less than the marginal social benefit. • This is a primary justification for the existence of government. Cost-Benefit Analysis • Governments engage in cost-benefit analysis when they estimate the social costs and social benefits of providing a public good. • Although governments should rely on cost-benefit analysis to determine how much of a public good to supply, doing so is problematic because individuals tend to overstate the good’s value to them Common Resources • A common resource is nonexcludable and rival in consumption: you can’t stop me from consuming the good, and more consumption by me means less of the good available for you. • Some examples of common resources are clean air and water as well as the diversity of animal and plant species on the planet (biodiversity). • In each of these cases, the fact that the good, though rival in consumption, is nonexcludable poses a serious problem. The Problem of Overuse • Common resources left to the free market suffer from overuse. • Overuse occurs when a user depletes the amount of the common resource available to others but does not take this cost into account when deciding how much to use the common resource. • In the case of a common resource, the marginal social cost of my use of that resource is higher than my individual marginal cost or the cost to me of using an additional unit of the good. • The following figure illustrates this point… A Common Resource Price of fish MSC POPT O S EMKT PMKT D QOPT QMKT Quantity of fish The supply curve S, which shows the marginal cost of production of the fishing industry, is composed of the individual supply curves of the individual fishermen. But each fisherman’s individual marginal cost does not include the cost that his or her actions impose on others: the depletion of the common resource. As a result, the marginal social cost curve, MSC, lies above the supply curve; in an unregulated market, the quantity of the common resource used, QMKT, exceeds the efficient quantity of use, Q. The Efficient Use and Maintenance of a Common Resource • To ensure efficient use of a common resource, society must find a way of getting individual users of the resource to take into account the costs they impose on other users. • Like negative externalities, a common resource can be efficiently managed by: – a tax or a regulation imposed on the use of the common resource. – making it excludable and assigning property rights to it. – creating a system of tradable licenses for the right to use the common resource. Artificially Scarce Goods • An artificially scarce good is excludable but nonrival in consumption. • Because the good is nonrival in consumption, the efficient price to consumers is zero. • However, because it is excludable, sellers charge a positive price, which leads to inefficiently low consumption. Private vs. Public Goods: Summary • Goods may be classified according to whether or not they are excludable and whether or not they are rival in consumption. • Free markets can deliver efficient levels of production and consumption for private goods, which are both excludable and rival in consumption. • When goods are nonexcludable, there is a free-rider problem: consumers will not pay for the good, leading to inefficiently low production. When goods are nonrival in consumption, they should be free, and any positive price leads to inefficiently low consumption. Private vs. Public Goods: Summary • A public good is nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption. In most cases a public good must be supplied by the government. The marginal social benefit of a public good is equal to the sum of the individual marginal benefits to each consumer. The efficient quantity of a public good is the quantity at which marginal social benefit equals the marginal cost of providing the good. Like a positive externality, marginal social benefit is greater than any one individual’s marginal benefit, so no individual is willing to provide the efficient quantity. • One rationale for the presence of government is that it allows citizens to tax themselves in order to provide public goods. Governments use cost-benefit analysis to determine the efficient provision of a public good. Private vs. Public Goods: Summary • A common resource is rival in consumption but nonexcludable. It is subject to overuse, because an individual does not take into account the fact that his or her use depletes the amount available for others. This is similar to the problem of a negative externality: the marginal social cost of an individual’s use of a common resource is always higher than his or her individual marginal cost. Pigouvian taxes, the creation of a system of tradable licenses, or the assignment of property rights are possible solutions. Private vs. Public Goods: Summary • Artificially scarce goods are excludable but nonrival in consumption. Because no marginal cost arises from allowing another individual to consume the good, the efficient price is zero. A positive price compensates the producer for the cost of production but leads to inefficiently low consumption. The problem of an artificially scarce good is similar to that of a natural monopoly. Externalities: The Economics of Pollution • Pollution is a bad thing. Yet most pollution is a side effect of activities that provide us with good things: – Our air is polluted by power plants generating the electricity that lights our cities, and our rivers are damaged by fertilizer runoff from farms that grow our food. • Pollution is a side effect of useful activities, so the optimal quantity of pollution isn’t zero. • Then, how much pollution should a society have? What are the costs and benefits of pollution? Costs and Benefits of Pollution • The marginal social cost of pollution is the additional cost imposed on society as a whole by an additional unit of pollution. • The marginal social benefit of pollution is the additional gain to society as a whole from an additional unit of pollution. • The socially optimal quantity of pollution is the quantity of pollution that society would choose if all the costs and benefits of pollution were fully accounted for. The Socially Optimal Quantity of Pollution Marginal social cost, marginal social benefit Marginal social cost, MSC, of pollution Socially optimal point $200 0 O QOPT Socially optimal quantity of pollution Marginal social benefit, MSB, of pollution Quantity of pollution emissions (tons) Pollution yields both costs and benefits. Here the curve MSC shows how the marginal cost to society as a whole from emitting one more ton of pollution emissions depends on the quantity of emissions. The curve MSB shows how the marginal benefit to society as a whole of emitting an additional ton of pollution emissions depends on the quantity of pollution emissions. The socially optimal quantity of pollution is QOPT; at that quantity, the marginal social benefit of pollution is equal to the marginal social cost, corresponding to $200. Pollution: An External Cost • An external cost is an uncompensated cost that an individual or firm imposes on others. • An external benefit is a benefit that an individual or firm confers on others without receiving compensation. • Pollution is an example of an external cost, or negative externality; in contrast, some activities can give rise to external benefits, or positive externalities. External costs and benefits are known as externalities. • Left to itself, a market economy will typically generate too much pollution because polluters have no incentive to take into account the costs they impose on others. Why a Market Economy Produces Too Much Pollution Marginal social cost, marginal social benefit $400 Marginal social cost at QMKT 300 Optimal Pigouvian 200 tax on pollution 100 Marginal social benefit at QMKT 0 MSC of pollution The market outcome is inefficient: marginal social cost of pollution exceeds marginal social benefit MSB of pollution O QOPT QH QMKT Socially optimal Market-determined quantity of pollution quantity of pollution Quantity of pollution Emissions (tons) In the absence of government intervention, the quantity of pollution will be QMKT, the level at which the marginal social benefit of pollution is zero. This is an inefficiently high quantity of pollution: the marginal social cost, $400, greatly exceeds the marginal social benefit, $0. An optimal Pigouvian tax of $200, the value of the marginal social cost of pollution when it equals the marginal social benefit of pollution, can move the market to the socially optimal quantity of pollution, QOPT. Private Solutions to Externalities • In an influential 1960 article, the economist Ronald Coase pointed out that, in an ideal world, the private sector could indeed deal with all externalities. • According to the Coase theorem, even in the presence of externalities an economy can always reach an efficient solution provided that the transaction costs—the costs to individuals of making a deal—are sufficiently low. • The costs of making a deal are known as transaction costs. Private Solutions to Externalities • The implication of Coase’s analysis is that externalities need not lead to inefficiency because individuals have an incentive to find a way to make mutually beneficial deals that lead them to take externalities into account when making decisions. • When individuals do take externalities into account, economists say that they internalize the externality. • Why can’t individuals always internalize externalities? • Transaction costs prevent individuals from making efficient deals. Private Solutions to Externalities Examples of transaction costs include the following: • The costs of communication among the interested parties—costs that may be very high if many people are involved. • The costs of making legally binding agreements that may be high if doing so requires the employment of expensive legal services. • Costly delays involved in bargaining—even if there is a potentially beneficial deal, both sides may hold out in an effort to extract more favorable terms, leading to increased effort and forgone utility. Thank You for Not Smoking • Second-hand smoke is an example of a negative externality. But how important is it? • A paper published in 1993 in the Journal of Economic Perspectives found that valuing the health costs of cigarettes depends on whether you count the costs imposed on members of smokers’ families. • If you don’t, the external costs of second-hand smoke have been estimated at about only $0.19 per pack smoked. • A 2005 study raised this estimate to $0.52 per pack smoked. If you include effects on smokers’ families, the number rises considerably. • If you include the effects of smoking by pregnant women on their unborn children’s future health, the cost is immense—$4.80 per pack. Policies Toward Pollution • Environmental standards are rules that protect the environment by specifying actions by producers and consumers. Generally such standards are inefficient because they are inflexible. • An emissions tax is a tax that depends on the amount of pollution a firm produces. • Tradable emissions permits are licenses to emit limited quantities of pollutants that can be bought and sold by polluters. • Taxes designed to reduce external costs are known as Pigouvian taxes. Policies Toward Pollution • When the quantity of pollution emitted can be directly observed and controlled, environmental goals can be achieved efficiently in two ways: emissions taxes and tradable emissions permits. • These methods are efficient because they are flexible, allocating more pollution reduction to those who can do it more cheaply. • An emissions tax is a form of Pigouvian tax, a tax designed to reduce external costs. • The optimal Pigouvian tax is equal to the marginal social cost of pollution at the socially optimal quantity of pollution. Production, Consumption, and Externalities • When there are external costs, the marginal social cost of a good or activity exceeds the industry’s marginal cost of producing the good. • In the absence of government intervention, the industry typically produces too much of the good. • The socially optimal quantity can be achieved by an optimal Pigouvian tax, equal to the marginal external cost, or by a system of tradable production permits. Positive Externalities and Consumption (a) Positive Externality Price, marginal social benefit of flu shot PMSB POPT PMKT Margin al external benefit O EMKT Price of flu shot S S MSB of flu shots Price to producers after subsidy Optimal Pigouvian subsidy Price to consumers after subsidy D QMKT QOPT (b) Optimal Pigouvian Subsidy Quantity of flu shots O EMKT D QT MK QOPT Quantity of flu shots Consumption of flu shots generates external benefits, so the marginal social benefit curve, MSB, of flu shots, corresponds to the demand curve, D, shifted upward by the marginal external benefit. Panel (a) shows that without government action, the market produces QMKT. It is lower than the socially optimal quantity of consumption, QOPT, the quantity at which MSB crosses the supply curve, S. At QMKT, the marginal social benefit of another flu shot, PMSB, is greater than the marginal benefit to consumers of another flu shot, PMKT. Panel (b) shows how an optimal Pigouvian subsidy to consumers, equal to the marginal external benefit, moves consumption to QOPT by lowering the price paid by consumers. Private Versus Social Benefits • The marginal social benefit of a good or activity is equal to the marginal benefit that accrues to consumers plus its marginal external benefit. Private Versus Social Benefits • A Pigouvian subsidy is a payment designed to encourage activities that yield external benefits. • A technology spillover is an external benefit that results when knowledge spreads among individuals and firms. The socially optimal quantity can be achieved by an optimal Pigouvian subsidy equal to the marginal external benefit. • An industrial policy is a policy that supports industries believed to yield positive externalities Private Versus Social Costs • The marginal social cost of a good or activity is equal to the marginal cost of production plus its marginal external cost. Negative Externalities and Production (a) Negative Externality Price, marginal social cost of livestock P MSC P OPT PMKT (b) Optimal Pigouvian Subsidy Price of livestock Marginal external cost MSC of livestock S O E Optimal Pigouvian subsidy MKT D Q Q OPT MKT Price to consumers after tax Quantity of livestock S O E MKT D Price to producers after tax Q Q OPT MKT Quantity of livestock Livestock production generates external costs, so the marginal social cost curve, MSC, of livestock, corresponds to the supply curve, S, shifted upward by the marginal external cost. Panel (a) shows that without government action, the market produces the quantity QMKT. It is greater than the socially optimal quantity of livestock production, QOPT, the quantity at which MSC crosses the demand curve, D. At QMKT, the market price, PMKT, is less than PMSC, the true marginal cost to society of livestock production. Panel (b) shows how an optimal Pigouvian tax on livestock production, equal to its marginal external cost, moves the production to QOPT, resulting in lower output and a higher price to consumers. Externalities: Summary 1. When pollution can be directly observed and controlled, government policies should be geared directly to producing the socially optimal quantity of pollution, the quantity at which the marginal social cost of pollution is equal to the marginal social benefit of pollution. 2. The costs to society of pollution are an example of an external cost; in some cases, however, economic activities yield external benefits. External costs and benefits are jointly known as externalities, with external costs called negative externalities and external benefits called positive externalities. Externalities: Summary (continued) 3. According to the Coase theorem, individuals can find a way to internalize the externality, making government intervention unnecessary, as long as transaction costs—the costs of making a deal—are sufficiently low. 4. Governments often deal with pollution by imposing environmental standards, a method, economists argue, that is usually an inefficient way to reduce pollution. Two efficient (cost-minimizing) methods for reducing pollution are emissions taxes, a form of Pigouvian tax, and tradable emissions permits. The optimal Pigouvian tax on pollution is equal to its marginal social cost at the socially optimal quantity of pollution. Externalities: Summary (continued) • When a good or activity yields external benefits, such as technology spillovers, the marginal social benefit of the good or activity is equal to the marginal benefit accruing to consumers plus its marginal external benefit. Without government intervention, the market produces too little of the good or activity. An optimal Pigouvian subsidy to producers, equal to the marginal external benefit, moves the market to the socially optimal quantity of production. This yields higher output and a higher price to producers. It is a form of industrial policy, a policy to support industries that are believed to generate positive externalities. Externalities: Summary (continued) • When only the original good or activity can be controlled, government policies are geared to influencing how much of it is produced. When there are external costs from production, the marginal social cost of a good or activity exceeds its marginal cost to producers, the difference being the marginal external cost. Without government action, the market produces too much of the good or activity. The optimal Pigouvian tax on production of the good or activity is equal to its marginal external cost, yielding lower output and a higher price to consumers. A system of tradable production permits for the right to produce the good or activity can also achieve efficiency at minimum cost. The Economics of Taxes • An excise tax is a tax on sales of a good or service. • Excise taxes: – raise the price paid by buyers and – reduce the price received by sellers • Excise taxes also drive a wedge between the two. Examples: Excise tax levied on sales of taxi rides and excise tax levied on purchases of taxi rides. Tax Incidence • The incidence of a tax is a measure of who really pays it. • Who really bears the tax burden (in the form of higher prices to consumers and lower prices to sellers) does not depend on who officially pays the tax. Depending on the shapes of supply and demand curves, the incidence of an excise tax may be divided differently. • The wedge between the demand price and supply price becomes the government’s “tax revenue.” Tax Incidence – Putting It Together • When the price elasticity of demand is higher than the price elasticity of supply, an excise tax falls mainly on producers. • When the price elasticity of supply is higher than the price elasticity of demand, an excise tax falls mainly on consumers. • So elasticity—not who officially pays the tax—determines the incidence of an excise tax. Who pays the FICA? • FICA stands for the Federal Insurance Contributions Act. It pays for the Social Security and Medicare systems - federal social insurance programs that provide income and medical care to retired and disabled Americans. • Most American workers pay 7.65% of their earnings in FICA. In addition, each employer is required to pay an amount equal to the contribution of his or her employee. • Is FICA really shared equally by workers and employers? • No, FICA falls mainly on the suppliers of labor, that is, workers in the form of lower wages, rather than by employers in lower profits. • Reason: when the price elasticity of demand is much higher than the price elasticity of supply, the burden of an excise tax falls mainly on the suppliers. The Revenue from an Excise Tax The general principle is: • The revenue collected by an excise tax is equal to the area of the rectangle whose height is the tax wedge between the supply and demand curves and whose width is the quantity transacted under the tax. Tax Rates and Revenue • A tax rate is the amount of tax people are required to pay per unit of whatever is being taxed. • In general, doubling the excise tax rate on a good or service won’t double the amount of revenue collected, because the tax increase will reduce the quantity of the good or service transacted. • In some cases, raising the tax rate may actually reduce the amount of revenue the government collects. Tax Rates and Revenue Price of hotel room (a) An excise tax of $20 $14 0 120 E D Area = tax revenue $14 0 120 110 S Excise 90 80 Area = tax = $20 per 70 tax revenue room Excise 80 tax = $60 per room 40 50 40 20 20 0 6,000 7,50010,000 (b) An excise tax of $60 Price of hotel room 15,000 Quantity of hotel rooms 0 S E D 2,5005,000 10,000 15,000 Quantity of hotel rooms In general, doubling the excise tax rate on a good or service won’t double the amount of revenue collected, because the tax increase will reduce the quantity of the good or service bought and sold. And the relationship between the level of the tax and the amount of revenue collected may not even be positive. Panel (a) shows the revenue raised by a tax rate of $20 per room, only half the tax rate in Figure 7-6. The tax revenue raised, equal to the area of the shaded rectangle, is $150,000, three- quarters as much as the revenue raised by a $40 tax rate. Panel (b) shows that the revenue raised by a $60 tax rate is also $150,000. So raising the tax rate from $40 to $60 actually reduces tax revenue. A Tax Reduces Consumer and Producer Surplus • A fall in the price of a good generates a gain in consumer surplus. • Similarly, a price increase causes a loss to consumers. • So it’s not surprising that in the case of an excise tax, the rise in the price paid by consumers causes a loss. • Meanwhile, the fall in the price received by producers leads to a fall in producer surplus. A tax reduces both, the CS and the PS. The Deadweight Loss of a Tax • Although consumers and producers are hurt by the tax, the government gains revenue. The revenue the government collects is equal to the tax per unit sold, T, multiplied by the quantity sold, QT. • But a portion of the loss to producers and consumers from the tax is not offset by a gain to the government. • The deadweight loss caused by the tax represents the total surplus lost to society because of the tax—that is, the amount of surplus that would have been generated by transactions that now do not take place because of the tax. The Deadweight Loss of a Tax Price S Deadweight loss P C Excise tax = T P E E P P D Q T Q E Quantity A tax leads to a deadweight loss because it creates inefficiency: some mutually beneficial transactions never take place because of the tax, namely the transactions QE−QT. The yellow area here represents the value of the deadweight loss: it is the total surplus that would have been gained from the QE− QT transactions. If the tax had not discouraged transactions—had the number of transactions remained at QE—no dead- weight loss would have been incurred. Cost of Collecting Taxes • The administrative costs of a tax are the resources used by government to collect the tax, and by taxpayers to pay it, over and above the amount of the tax, as well as to evade it. • The total inefficiency caused by a tax is the sum of its deadweight loss and its administrative costs. The general rule for economic policy is that, other things equal, a tax system should be designed to minimize the total inefficiency it imposes on society. Deadweight Loss and Elasticities • To minimize the efficiency costs of taxation, one should choose to tax only those goods for which demand or supply, or both, is relatively inelastic. • For such goods, a tax has little effect on behavior because behavior is relatively unresponsive to changes in the price. Deadweight Loss and Elasticities • In the extreme case in which demand is perfectly inelastic (a vertical demand curve), the quantity demanded is unchanged by the imposition of the tax. As a result, the tax imposes no deadweight loss. • Similarly, if supply is perfectly inelastic (a vertical supply curve), the quantity supplied is unchanged by the tax and there is also no deadweight loss. Deadweight Loss and Elasticities • If the goal in choosing whom to tax is to minimize deadweight loss, then taxes should be imposed on goods and services that have the most inelastic response—that is, goods and services for which consumers or producers will change their behavior the least in response to the tax. Tax Fairness and Tax Efficiency Two principles: • According to the benefits principle of tax fairness, those who benefit from public spending should bear the burden of the tax that pays for that spending. • According to the ability-to-pay principle of tax fairness, those with greater ability to pay a tax should pay more tax. • A lump-sum tax is the same for everyone, regardless of any actions people take. Tax Fairness and Tax Efficiency • The fairest taxes, in terms of the ability-to-pay principle, distort incentives the most and perform badly on efficiency grounds. • In a well-designed tax system, there is a trade-off between equity and efficiency: the system can be made more efficient only by making it less fair, and vice versa. Federal Tax Philosophy • What is the principle underlying the federal tax system? • It depends on the tax: – Income tax accounts for about half of all federal revenue. The structure of the income tax reflects the ability-to-pay principle: families with low incomes pay little or no income tax. In fact, some families pay negative income tax. – The second most important federal tax is FICA (discussed earlier). Federal Tax Philosophy Federal Tax Philosophy • As you can see, low-income families actually paid negative income tax through the Earned Income Tax Credit program. • Even middle-income families paid a substantially smaller share of total income tax collected than their share of total income. • In contrast, the fifth or top quintile, the richest 20% of families, paid a much higher share of total federal income tax collected compared with their share of total income. • The fourth column shows the share of total payroll tax collected that is paid by each quintile, and the results are very different: the share of total payroll tax paid by the top quintile is substantially less than their share of total income. Understanding the Tax System • The tax base is the measure or value, such as income or property value, that determines how much tax an individual or firm pays. • The tax structure specifies how the tax depends on the tax base. • Once the tax base has been defined, the next question is how the tax depends on the base. The simplest tax structure is a proportional tax, also sometimes called a flat tax, which is the same percentage of the base regardless of the taxpayer’s income or wealth. Understanding the Tax System Some important taxes and their tax bases are as follows: • Income tax: a tax that depends on the income of an individual or a family from wages and investments • Payroll tax: a tax that depends on the earnings an employer pays to an employee • Sales tax: a tax that depends on the value of goods sold (also known as an excise tax) • Profits tax: a tax that depends on a firm’s profits • Property tax: a tax that depends on the value of property, such as the value of a home • Wealth tax: a tax that depends on an individual’s wealth Understanding the Tax System • Once the tax base has been defined, the next question is how the tax depends on the base. The simplest tax structure is a proportional tax, also sometimes called a flat tax, which is the same percentage of the base regardless of the taxpayer’s income or wealth. Understanding the Tax System • A progressive tax takes a larger share of the income of highincome taxpayers than of low-income taxpayers. • A regressive tax takes a smaller share of the income of highincome taxpayers than of low-income taxpayers. • The marginal tax rate is the percentage of an increase in income that is taxed away. Different Taxes, Different Principles • There are two main reasons for the mixture of regressive and progressive taxes in the U.S. system: the difference between levels of government and the fact that different taxes are based on different principles. • State and especially local governments generally do not make much effort to apply the ability-to-pay principle. This is largely because they are subject to tax competition: a state or local government that imposes high taxes on people with high incomes faces the prospect that those people may move to other locations where taxes are lower. Taxing Income versus Taxing Consumption • The U.S. government taxes people mainly on the money they make, not on the money they spend on consumption. • A system that taxes income rather than consumption discourages people from saving and investing, instead providing an incentive to spend their income today. • Americans tend to save too little for retirement and health expenses in their later years. • Low savings and investing slow down economic growth. • Moving from a system that taxes income to one that taxes consumption would solve this problem. • Currently, the U.S. does not have a value-added tax because it is difficult to make a consumption tax progressive and a VAT typically has very high administrative costs. The Top Marginal Income Tax Rate • The amount of money an American owes in federal income taxes is defined in terms of marginal tax rates on successively higher “brackets” of income. • In 2007 a single person paid: – 10% on the first $7,825 of taxable income (i.e. income after subtracting exemptions and deductions); – 15% on the next $24,050; – and so on up to a top rate of 35% on his or her income if over $349,700. • Relatively few people (less than 1% of taxpayers) have incomes high enough to pay the top marginal rate (77% of Americans pay no income tax or they fall into either the 10% or 15% bracket). Summary: Taxes • “Excise taxes” — taxes on the purchase or sale of a good—raise the price paid by consumers and reduce the price received by producers, driving a wedge between the two.The incidence of the tax—how the burden of the tax is divided between consumers and producers—does not depend on who officially pays the tax. • The incidence of an excise tax depends on the price elasticities of supply and demand. If the price elasticity of demand is higher than the price elasticity of supply, the tax falls mainly on producers; if the price elasticity of supply is higher than the price elasticity of demand, the tax falls mainly on consumers. Summary: Taxes (Continued) • The tax revenue generated by a tax depends on the tax rate and on the number of units transacted with the tax. Excise taxes cause inefficiency in the form of deadweight loss because they discourage some mutually beneficial transactions. Taxes also impose administrative costs —resources used to collect the tax. • An excise tax generates revenue for the government, but lowers total surplus. The loss in total surplus exceeds the tax revenue, resulting in a deadweight loss to society. This deadweight loss is represented by a triangle, the area of which equals the value of the transactions discouraged by the tax. The greater the elasticity of demand or supply, or both, the larger the deadweight loss from a tax. If either demand or supply is perfectly inelastic, there is no deadweight loss from a tax. Summary: Taxes (Continued) An efficient tax minimizes both the sum of the deadweight loss due to distorted incentives and the administrative costs of the tax. However, tax fairness, or tax equity, is also a goal of tax policy. There are two major principles of tax fairness, the benefits principle and the ability-to-pay principle. The most efficient tax, a lumpsum tax, does not distort incentives but performs badly in terms of fairness. The fairest taxes in terms of the ability-to-pay principle, however, distort incentives the most and perform badly on efficiency grounds. So in a well-designed tax system, there is a trade-off between equity and efficiency. Summary: Taxes (Continued) • Every tax consists of a tax base, which defines what is taxed, and a tax structure, which specifies how the tax depends on the tax base. Different tax bases give rise to different taxes—the income tax, payroll tax , sales tax, profits tax , property tax, and wealth tax. • A tax is progressive if higher-income people pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes than lower-income people and regressive if they pay a lower percentage. Progressive taxes are often justified by the ability-to-pay principle. However, a highly progressive tax system significantly distorts incentives because it leads to a high marginal tax rate, the percentage of an increase in income that is taxed away, on high earners. The U.S. tax system is progressive overall, although it contains a mixture of progressive and regressive taxes.