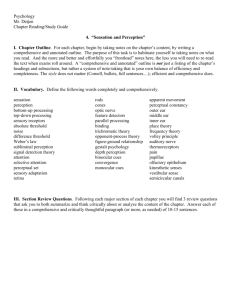

Review Slides_Visual Perception & Audition

REVIEW SLIDES

Visual Perception & Audition

Quiz on Tuesday, 12/9

Parallel Processing

Turning light into the mental act of seeing: light waves chemical reactions neural impulses features objects and one more step...

Parallel processing: building perceptions out of sensory details processed simultaneously in different areas of the brain. For example, a flying bird is processed as:

Visual Processing

Color Vision

Young-Helmholtz Trichromatic

(Three-Color) Theory

According to this theory, there are three types of color receptor cones--red, green, and blue. All the colors we perceive are created by light waves stimulating combinations of these cones.

Color Blindness

People missing red cones or green cones have trouble differentiating red from green, and thus have trouble reading the numbers to the right.

Opponent-process theory refers to the neural process of perceiving white as the opposite of perceiving black; similarly, yellow vs. blue , and red vs. green are opponent processes.

Opponent-Process Theory Test

The dot, the dot, keep staring at the dot in the center…

Turning light waves into mental images/movies...

Visual Perceptual Organization

We have perceptual processes for enabling us to organize perceived colors and lines into objects:

grouping incomplete parts into gestalt wholes

seeing figures standing out against background

perceiving form and depth

keeping a sense of shape, size, and color constancy despite changes in visual information

using experience to guide visual interpretation

Restored vision and sensory restriction

Perceptual adaptation

Our senses take in the blue information on the right.

However, our perceptual processes turn this into:

1. a white paper with blue circle dots, with a cube floating in front.

2. a white paper with blue circle holes, through which you can see a cube.

3. a cube sticking out to the top left, or bottom right.

4. blue dots (what cube?) with angled lines inside.

The Role of

Perception

Figure-Ground Perception

In most visual scenes, we pick out objects and figures, standing out against a background.

Some art muddles this ability by giving us two equal choices about what is figure and what is “ground”:

Goblet or two faces?

Stepping man, or arrows?

Grouping: How We Make Gestalts

“Gestalt” refers to a meaningful pattern/configuration, forming a “whole” that is more than the sum of its parts.

Three of the ways we group visual information into

“wholes” are proximity, continuity, and closure.

Grouping Principles

Which ones influence perception here?

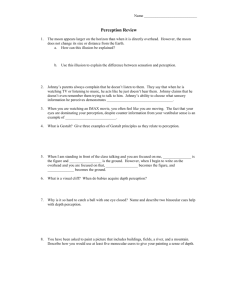

Visual Cliff: A Test of Depth Perception

Babies seem to develop this ability at crawling age.

Even newborn animals fear the perceived cliff.

Perceiving Depth: Binocular Methods

Unlike other animals, humans have two eyes in the front of our head.

This gives us retinal disparity ; the two eyes have slightly different views. The more different the views are, the closer the object must be.

This is used in 3D movies to create the illusion of depth, as each eye gets a different view of “close” objects.

How do we perceive depth from a 2D image?... by using monocular (needing only one eye) cues

Monocular Cue: Interposition

Interposition:

When one object appears to block the view of another, we assume that the blocking object is in a position between our eyes and the blocked object.

Monocular Cue:

Relative Size

We intuitively know to interpret familiar objects (of known size) as farther away when they appear smaller.

Monocular Cues:

Linear Perspective and Interposition

The flowers in the distance seem farther away because the rows converge. Our brain reads this as a sign of distance.

Tricks Using

Linear

Perspective

These two red lines meet the retina as being the same size

However, our perception of distance affects our perception of length.

Monocular Cue: Relative Height

We tend to perceive the higher part of a scene as farther away.

This scene can look like layers of buildings, with the highest part of the picture as the sky.

If we flip the picture, then the black part can seem like night sky… because it is now highest in the picture.

Monocular Cues: Shading Effects

Shading helps our perception of depth.

Does the middle circle bulge out or curve inward?

How about now?

Light and shadow create depth cues.

Monocular Cues: Relative Motion

When we are moving, we can tell which objects are farther away because it takes longer to pass them.

A picture of a moon on a sign would zip behind us, but the actual moon is too far for us to pass.

http://psych.hanover.edu/krantz/motionparallax/motionparallax.html

Perceptual Constancy

Our ability to see objects as appearing the same even under different lighting conditions, at different distances and angles, is called perceptual constancy . Perceptual constancy is a top-down process.

Examples:

color and brightness constancy

shape and size constancy

Color Constancy

This ability to see a consistent color in changing

illumination helps us see the three sides as all being yellow, because our brain compensates for shading.

As a result, we interpret three same-color blue dots, with shades that are not adjusted for shading, as being of three different colors.

Brightness Constancy

On this screen, squares A and B are exactly the same shade of gray.

You can see this when you connect them.

So why does B look lighter?

Shape Constancy

Shape constancy refers to the ability to perceive objects as having a constant shape despite receiving different sensory images. This helps us see the door as a rectangle as it opens. Because of this, we may think the red shapes on screen are also rectangles.

Size Constancy

We have an ability to use distance-related context cues to help us see objects as the same size even if

the image on the retina becomes smaller.

The Ames room was invented by American ophthalmologist Adelbert Ames, Jr. in 1934.

The Ames room was designed to manipulate distance cues to make two same-sized girls appear very different in size.

Visual Interpretation: Restored vision, sensory restriction

Experience shapes our visual perception

People have grown up without vision but then have surgically gained sight in adulthood. They learned to interpret depth, motion, and figureground distinctions, but could not differentiate shapes or even faces.

Animals raised at an early age with restrictions, e.g. without seeing horizontal lines, later seem unable to learn to perceive such lines.

We must practice our perception skills during a critical period of development, or these skills may not develop.

Being blind between ages 3 and 46 cost

Mike his ability to learn individual faces.

Perceptual Adaptation

After our sensory information is distorted, such as by a new pair of glasses or by delayed audio on a television, humans may at first be disoriented but can learn to adjust and function.

This man could learn eventually to fly an airplane wearing these unusual goggles, but here, at first, he is disoriented by having his world turned upside down.

The Nonvisual Senses

There’s more to Sensation and

Perception than meets the eye

Hearing: From sound to ear to perceiving pitch and locating sounds.

Touch and Pain sensation and perception

Taste and Smell

Perception of Body Position and

Movement

Hearing

How do we take a sensation based on sound waves and turn it into perceptions of music, people, and actions?

How do we distinguish among thousands of pitches and voices?

Hearing/Audition: Starting with Sound

Length of the sound wave; perceived as high and low sounds

(pitch)

Height or intensity of sound wave; perceived as loud and soft

(volume)

Perceived as sound quality or resonance

Sound Waves Reach The Ear

The outer ear collects sound and funnels it to the eardrum.

In the middle ear, the sound waves hit the eardrum and move the hammer, anvil, and stirrup in ways that amplify the vibrations. The stirrup then sends these vibrations to the oval window of the cochlea.

In the inner ear, waves of fluid move from the oval window over the cochlea’s

“hair” receptor cells. These cells send signals through the auditory nerves to the temporal lobe of the brain.

The Middle and Inner Ear

Conduction Hearing Loss: when the middle ear isn’t conducting sound well to the cochlea

Sensorineural Hearing Loss: when the receptor cells aren’t sending messages through the auditory nerves

Preventing

Hearing Loss

Exposure to sounds that are too loud to talk over can cause damage to the inner ear, especially the hair cells.

Structures of the middle and inner ear can also be damaged by disease.

Prevention methods include limiting exposure to noises over

85 decibels and treating ear infections.

Treating Hearing Loss

People with conduction hearing loss may be helped by hearing aids. These aids amplify sounds striking the eardrum, ideally amplifying only softer sounds or higher frequencies.

People with sensorineural hearing loss can benefit from a cochlear implant.

The implant does the work of the hair cells in translating sound waves into electrical signals to be sent to the brain.

Sound Perception: Loudness

Loudness refers to more intense sound vibrations. This causes a greater

number of hair cells to send signals to the brain.

Soft sounds only activate certain hair cells; louder sounds move those hair cells AND their neighbors.

Sound Perception: Pitch

How does the inner ear turn sound frequency into neural frequency?

Place theory

At high sound frequencies, signals are generated at different locations in the cochlea, depending on pitch.

The brain reads pitch by reading the location where the signals are coming from.

Frequency theory

At low sound frequencies, hair cells send signals at whatever rate the sound is received.

Volley Principle

At ultra high frequencies, receptor cells fire in succession, combing signals to reach higher firing rates.

Sound Perception: Localization

How do we seem to know the location of the source of a sound?

Sounds usually reach one of our ears sooner, and with more clarity, than they reach the other ear.

The brain uses this difference to generate a perception of the direction the sound was coming from.