The Robotic Joints

advertisement

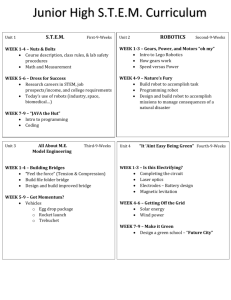

MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY Mechanical Engineering Department ME 445 Integrated Manufacturing Systems 2004 1 ROBOTICS 2004 2 Robotics Terminology Robot: An electromechanical device with multiple degreesof-freedom (DOF) that is programmable to accomplish a variety of tasks. Industrial robot:The Robotics Industries Association (RIA) defines robot in the following way: “An industrial robot is a programmable, multifunctional manipulator designed to move materials, parts, tools, or special devices through variable programmed motions for the performance of a variety of tasks” 2004 3 Robotics Terminology Robotics: The science of robots. Humans working in this area are called roboticists. 2004 4 Robotics Terminology DOF degrees-of-freedom: the number of independent motions a device can make. (Also called mobility) five degrees of freedom 2004 5 Robotics Terminology Manipulator: Electromechanical device capable of interacting with its environment. Anthropomorphic: Like human beings. ROBONAUT (ROBOtic astroNAUT), an anthropomorphic robot with two arms, 2004 two hands, a head, a torso, and a stabilizing leg. 6 Robotics Terminology End-effector: The tool, gripper, or other device mounted at the end of a manipulator, for accomplishing useful tasks. 2004 7 Robotics Terminology Workspace: The volume in space that a robot’s endeffector can reach, both in position and orientation. 2004 A cylindrical robots’ half workspace 8 Robotics Terminology Position: The something. translational (straight-line) location of Orientation: The rotational (angle) location of something. A robot’s orientation is measured by roll, pitch, and yaw angles. Link: A rigid piece of material connecting joints in a robot. Joint: The device which allows relative motion between two links in a robot. 2004 A robot joint 9 Robotics Terminology Kinematics: The study of motion without regard to forces. Dynamics: The study of motion with regard to forces. Actuator: Provides force for robot motion. Sensor: Reads variables in robot motion for use in control. 2004 10 Robotics Terminology Speed •The amount of distance per unit time at which the robot can move, usually specified in inches per second or meters per second. •The speed is usually specified at a specific load or assuming that the robot is carrying a fixed weight. •Actual speed may vary depending upon the weight carried by the robot. Load Bearing Capacity •The maximum weight-carrying capacity of the robot. •Robots that carry large weights, but must still be precise are expensive. 2004 11 Robotics Terminology Accuracy •The ability of a robot to go to the specified position without making a mistake. •It is impossible to position a machine exactly. •Accuracy is therefore defined as the ability of the robot to position itself to the desired location with the minimal error (usually 25 mm). Repeatability •The ability of a robot to repeatedly position itself when asked to perform a task multiple times. •Accuracy is an absolute concept, repeatability is relative. •A robot that is repeatable may not be very accurate, visa versa. 2004 12 Robotics Terminology 2004 13 Robotics History 350 B.C The Greek mathematician, Archytas builds a mechanical bird named "the Pigeon" that is propelled by steam. 322 B.C. The Greek philosopher Aristotle writes; “If every tool, when ordered, or even of its own accord, could do the work that befits it... then there would be no need either of apprentices for the master workers or of slaves for the lords.”... hinting how nice it would be to have a few robots around. 200 B.C. The Greek inventor and physicist Ctesibus of Alexandria 2004 designs water clocks that have movable figures on them. 14 Robotics History 1495 Leonardo Da Vinci designs a mechanical device that looks like an armored knight. The mechanisms inside "Leonardo's robot" are designed to make the knight move as if there was a real person inside. 2004 15 Robotics History Leonardo’s Robot 2004 16 Robotics History 1738 Jacques de Vaucanson begins building automata. The first one was the flute player that could play twelve songs. 1770 Swiss clock maker and inventor of the modern wristwatch Pierre Jaquet-Droz start making automata for European royalty. He create three doll, one can write, another plays music, and the third draws pictures. 1801 Joseph Jacquard builds an automated loom that is 2004 17 controlled with punched cards. Robotics History Joseph Jacquard’s Automated Loom 2004 18 Robotics History 1898 Nikola Tesla builds and demonstrates a remote controlled robot boat. 2004 19 Robotics History 1921 Czech writer Karel Capek introduced the word "Robot" in his play "R.U.R" (Rossuum's Universal Robots). "Robot" in Czech comes from the word "robota", meaning "compulsory labor“. 1940 Issac Asimov produces a series of short stories about robots starting with "A Strange Playfellow" (later renamed "Robbie") for Super Science Stories magazine. The story is about a robot and its affection for a child that it is bound to protect. Over the next 10 years he produces more stories about robots that are eventually recompiled into the volume "I, Robot" in 1950. Issac Asimov's most important contribution to the history of the robot is the creation of his “Three Laws of 2004 20 Robotics”. Robotics History Three Laws of Robotics: 1. A robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm. 2. A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law. 3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law. Asimov later adds a "zeroth law" to the list: Zeroth law: A robot may not injure humanity, or, through inaction, allow humanity to come to harm. 2004 21 Robotics History 1946 George Devol patents a playback device for controlling machines. 1961 Heinrich Ernst develops the MH-1, a computer operated mechanical hand at MIT. 1961 Unimate, the company of Joseph Engleberger and George Devoe, built the first industrial robot, the PUMA (Programmable Universal Manipulator Arm). 1966 The Stanford Research Institute creates Shakey the first mobile robot to know and react to its own actions. 2004 22 Robotics History Unimate PUMA 2004 SRI Shakey 23 Robotics History 1969 Victor Scheinman creates the Stanford Arm. The arm's design becomes a standard and is still influencing the design of robot arms today. 2004 24 Robotics History 1976 Shigeo Hirose designs the Soft Gripper at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. It is designed to wrap around an object in snake like fashion. 1981 Takeo Kanade builds the direct drive arm. It is the first to have motors installed directly into the joints of the arm. This change makes it faster and much more accurate than previous robotic arms. 1989 A walking robot named Genghis is unveiled by the Mobile Robots Group at MIT. 2004 25 Robotics History 1993 Dante an 8-legged walking robot developed at Carnegie Mellon University descends into Mt. Erebrus, Antarctica. Its mission is to collect data from a harsh environment similar to what we might find on another planet. 1994 Dante II, a more robust version of Dante I, descends into the crater of Alaskan volcano Mt. Spurr. The mission is considered a success. 2004 26 Robotics History 1996 Honda debuts the P3. 2004 27 Robotics History 1997 The Pathfinder Mission lands on Mars 2004 1999 SONY releases the AIBO robotic pet. 28 Robotics History 2000 Honda debuts new humanoid robot ASIMO. 2004 29 Industrial Robots 2004 30 Power Sources for Robots • An important element of a robot is the drive system. The drive system supplies the power, which enable the robot to move. • The dynamic performance of a robot mainly depends on the type of power source. 2004 31 There are basically three types of power sources for robots: 1. Hydraulic drive • Provide fast movements • Preferred for moving heavy parts • Preferred to be used in explosive environments • Occupy large space area • There is a danger of oil leak to the shop floor 2004 32 2. Electric drive • Slower movement compare to the hydraulic robots • Good for small and medium size robots • Better positioning accuracy and repeatability • stepper motor drive: open loop control • DC motor drive: closed loop control • Cleaner environment • The most used type of drive in industry 2004 33 3. Pneumatic drive • Preferred for smaller robots • Less expensive than electric or hydraulic robots • Suitable for relatively less degrees of freedom design • Suitable for simple pick and place application • Relatively cheaper 2004 34 Robotic Sensors • Sensors provide feedback to the control systems and give the robots more flexibility. • Sensors such as visual sensors are useful in the building of more accurate and intelligent robots. • The sensors can be classified as follows: 2004 35 1. Position sensors: Position sensors are used to monitor the position of joints. Information about the position is fed back to the control systems that are used to determine the accuracy of positioning. 2004 36 2. Range sensors: Range sensors measure distances from a reference point to other points of importance. Range sensing is accomplished by means of television cameras or sonar transmitters and receivers. 2004 37 3. Velocity Sensors: They are used to estimate the speed with which a manipulator is moved. The velocity is an important part of the dynamic performance of the manipulator. The DC tachometer is one of the most commonly used devices for feedback of velocity information. The tachometer, which is essentially a DC generator, provides an output voltage proportional to the angular velocity of the armature. This information is fed back to the controls for proper regulation of the motion. 2004 38 4. Proximity Sensors: They are used to sense and indicate the presence of an object within a specified distance without any physical contact. This helps prevent accidents and damage to the robot. – infra red sensors – acoustic sensors – touch sensors – force sensors – tactile sensors for more accurate data on the position 2004 39 The Hand of a Robot: End-Effector The end-effector (commonly known as robot hand) mounted on the wrist enables the robot to perform specified tasks. Various types of end-effectors are designed for the same robot to make it more flexible and versatile. End-effectors are categorized into two major types: grippers and tools. 2004 40 The Hand of a Robot: End-Effector 2004 41 The Hand of a Robot: End-Effector Grippers are generally used to grasp and hold an object and place it at a desired location. – mechanical grippers – vacuum or suction cups – magnetic grippers – adhesive grippers – hooks, scoops, and so forth 2004 42 The Hand of a Robot: End-Effector At times, a robot is required to manipulate a tool to perform an operation on a workpiece. In such applications the endeffector is a tool itself – spot-welding tools – arc-welding tools – spray-painting nozzles – rotating spindles for drilling – rotating spindles for grinding 2004 43 Robot Movement and Precision Speed of response and stability are two important characteristics of robot movement. • Speed defines how quickly the robot arm moves from one point to another. • Stability refers to robot motion with the least amount of oscillation. A good robot is one that is fast enough but at the same time has good stability. 2004 44 Robot Movement and Precision Speed and stability are often conflicting goals. However, a good controlling system can be designed for the robot to facilitate a good trade-off between the two parameters. 2004 45 The precision of robot movement is defined by three basic features: 1. Spatial resolution: The spatial resolution of a robot is the smallest increment of movement into which the robot can divide its work volume. It depends on the system’s control resolution and the robot's mechanical inaccuracies. 2004 46 2. Accuracy: Accuracy can be defined as the ability of a robot to position its wrist end at a desired target point within its reach. In terms of control resolution, the accuracy can be defined as one-half of the control resolution. This definition of accuracy applies in the worst case when the target point is between two control points.The reason is that displacements smaller than one basic control resolution unit (BCRU) can be neither programmed nor measured and, on average, they account for one-half BCRU. 2004 47 The accuracy of a robot is affected by many factors. For example, when the arm is fully stretched out, the mechanical inaccuracies tend to be larger because the loads tend to cause deflection. 2004 48 3. Repeatability: It is the ability of the robot to position the end effector to the previously positioned location. A C + + + ++ + + + + + + ++ B + + + + ++ + x xx x xx x x x xxx xx xx xx x x x x x 2004 x 49 The Robotic Joints A robot joint is a mechanism that permits relative movement between parts of a robot arm. The joints of a robot are designed to enable the robot to move its end-effector along a path from one position to another as desired. 2004 50 The Robotic Joints The basic movements required for a desired motion of most industrial robots are: • 1. rotational movement: This enables the robot to place its arm in any direction on a horizontal plane. • 2. Radial movement: This enables the robot to move its end-effector radially to reach distant points. • 3. Vertical movement: This enables the robot to take its end-effector to different heights. 2004 51 The Robotic Joints These degrees of freedom, independently or in combination with others, define the complete motion of the end-effector. These motions are accomplished by movements of individual joints of the robot arm. The joint movements are basically the same as relative motion of adjoining links. Depending on the nature of this relative motion, the joints are classified as prismatic or revolute. 2004 52 The Robotic Joints • Prismatic joints (L) are also known as sliding as well as linear joints. • They are called prismatic because the cross section of the joint is considered as a generalized prism. They permit links to move in a linear relationship. 2004 53 The Robotic Joints Revolute joints permit only angular motion between links. Their variations include: – Rotational joint (R) – Twisting joint (T) – Revolving joint (V) 2004 54 The Robotic Joints In a prismatic joint, also known as a sliding or linear joint (L), the links are generally parallel to one 2004 55 The Robotic Joints A rotational joint (R) is identified by its motion, rotation about an axis perpendicular to the adjoining links. Here, the lengths of adjoining links do not change but the relative position of the links with respect to one another changes as the rotation takes place. 2004 56 The Robotic Joints 2004 57 The Robotic Joints A twisting joint (T) is also a rotational joint, where the rotation takes place about an axis that is parallel to both adjoining links. 2004 58 The Robotic Joints A revolving joint (V) is another rotational joint, where the rotation takes place about an axis that is parallel to one of the adjoining links. Usually, the links are aligned perpendicular to one another at this kind of joint. The rotation involves revolution of one link about another. 2004 59 The Robotic Joints 2004 60 2004 61 ROBOT CLASSIFICATION Robots may be classified, based on: – physical configuration – control systems 2004 62 ROBOT CLASSIFICATION Classification Based on Physical Configuration: – 1. Cartesian configuration – 2. Cylindrical configuration – 3. Polar configuration – 4. Joint-arm configuration 2004 63 ROBOT CLASSIFICATION Cartesian Configuration: • Robots with Cartesian configurations consists of links connected by linear joints (L). Gantry robots are Cartesian robots (LLL). 2004 64 Cartesian Robots A robot with 3 prismatic joints – the axes consistent with a Cartesian coordinate system. Commonly used for: •pick and place work •assembly operations •handling machine tools •arc welding 2004 65 Cartesian Robots Advantages: • ability to do straight line insertions into furnaces. • easy computation and programming. • most rigid structure for given length. Disadvantages: • requires large operating volume. • exposed guiding surfaces require covering in corrosive or dusty environments. • can only reach front of itself • axes hard to seal 2004 66 ROBOT CLASSIFICATION Cylindrical Configuration: • Robots with cylindrical configuration have one rotary ( R) joint at the base and linear (L) joints succeeded to connect the links. 2004 67 Cylindrical Robots A robot with 2 prismatic joints and a rotary joint – the axes consistent with a cylindrical coordinate system. Commonly used for: •handling at die-casting machines •assembly operations •handling machine tools •spot welding 2004 68 Cylindrical Robots Advantages: • can reach all around itself • rotational axis easy to seal • relatively easy programming • rigid enough to handle heavy loads through large working space • good access into cavities and machine openings Disadvantages: • can't reach above itself • linear axes is hard to seal • won’t reach around obstacles • exposed drives are difficult to cover from dust and liquids 2004 69 ROBOT CLASSIFICATION Polar Configuration: • Polar robots have a work space of spherical shape. Generally, the arm is connected to the base with a twisting (T) joint and rotatory (R) and linear (L) joints follow. 2004 70 ROBOT CLASSIFICATION • The designation of the arm for this configuration can be TRL or TRR. • Robots with the designation TRL are also called spherical robots. Those with the designation TRR are also called articulated robots. An articulated robot more closely resembles the human arm. 2004 71 ROBOT CLASSIFICATION Joint-arm Configuration: • The jointed-arm is a combination of cylindrical and articulated configurations. The arm of the robot is connected to the base with a twisting joint. The links in the arm are connected by rotatory joints. Many commercially available robots have this configuration. 2004 72 ROBOT CLASSIFICATION 2004 73 Articulated Robots A robot with at least 3 rotary joints. Commonly used for: •assembly operations •welding •weld sealing •spray painting •handling at die casting or fettling machines 2004 74 Articulated Robots Advantages: • all rotary joints allows for maximum flexibility • any point in total volume can be reached. • all joints can be sealed from the environment. Disadvantages: • extremely difficult to visualize, control, and program. • restricted volume coverage. • low accuracy 2004 75 SCARA (Selective Compliance Articulated Robot Arm) Robots A robot with at least 2 parallel rotary joints. Commonly used for: •pick and place work •assembly operations 2004 76 SCARA (Selective Compliance Articulated Robot Arm) Robots Advantages: • high speed. • height axis is rigid • large work area for floor space • moderately easy to program. Disadvantages: • limited applications. • 2 ways to reach point • difficult to program off-line 2004 • highly complex arm 77 Spherical/Polar Robots A robot with 1 prismatic joint and 2 rotary joints – the axes consistent with a polar coordinate system. Commonly used for: •handling at die casting or fettling machines •handling machine tools •arc/spot welding 2004 78 Spherical/Polar Robots Advantages: • large working envelope. • two rotary drives are easily sealed against liquids/dust. Disadvantages: • complex coordinates more difficult to visualize, control, and program. • exposed linear drive. • low accuracy. 2004 79 ROBOT CLASSIFICATION Classification Based on Control Systems: – 1. Point-to-point (PTP) control robot – 2. Continuous-path (CP) control robot – 3. Controlled-path robot 2004 80 Point to Point Control Robot (PTP): • The PTP robot is capable of moving from one point to another point. • The locations are recorded in the control memory. PTP robots do not control the path to get from one point to the next point. • Common applications include: – – – – – 2004 component insertion spot welding hole drilling machine loading and unloading assembly operations 81 Continuous-Path Control Robot (CP): • The CP robot is capable of performing movements along the controlled path. With CP from one control, the robot can stop at any specified point along the controlled path. • All the points along the path must be stored explicitly in the robot's control memory. Applications Straight-line motion is the simplest example for this type of robot. Some continuous-path controlled robots also have the capability to follow a smooth curve path that has been defined by the programmer. In such cases the programmer manually moves the robot arm through the desired path and the controller unit stores a large number of individual point locations along the path in memory (teach-in). 2004 82 Continuous-Path Control Robot (CP): Typical applications include: – spray painting – finishing – gluing – arc welding operations 2004 83 Controlled-Path Robot: • In controlled-path robots, the control equipment can generate paths of different geometry such as straight lines, circles, and interpolated curves with a high degree of accuracy. Good accuracy can be obtained at any point along the specified path. • Only the start and finish points and the path definition function must be stored in the robot's control memory. It is important to mention that all controlled-path robots have a servo capability to correct their path. 2004 84 Robot Reach: Robot reach, also known as the work envelope or work volume, is the space of all points in the surrounding space that can be reached by the robot arm. Reach is one of the most important characteristics to be considered in selecting a suitable robot because the application space should not fall out of the selected robot's reach. 2004 85 Robot Reach: • For a Cartesian configuration the reach is a rectangular-type space. • For a cylindrical configuration the reach is a hollow cylindrical space. • For a polar configuration the reach is part of a hollow spherical shape. • Robot reach for a jointed-arm configuration does not have a specific shape. 2004 86 2004 87 ROBOT MOTION ANALYSIS In robot motion analysis we study the geometry of the robot arm with respect to a reference coordinate system, while the end-effector moves along the prescribed path . 2004 88 ROBOT MOTION ANALYSIS The kinematic analysis involves two different kinds of problems: – 1. Determining the coordinates of the endeffector or end of arm for a given set of joints coordinates. – 2. Determining the joints coordinates for a given location of the end-effector or end of arm. 2004 89 ROBOT MOTION ANALYSIS The position, V, of the end-effector can be defined in the Cartesian coordinate system, as: V = (x, y) 2004 90 ROBOT MOTION ANALYSIS Generally, for robots the location of the end-effector can be defined in two systems: a. joint space and b. world space (also known as global space) 2004 91 ROBOT MOTION ANALYSIS In joint space, the joint parameters such as rotating or twisting joint angles and variable link lengths are used to represent the position of the end-effector. – Vj = (q, a) – Vj = (L1, , L2) – Vj = (a, L2) for RR robot for LL robot for TL robot where Vj refers to the position of the endeffector in joint space. 2004 92 ROBOT MOTION ANALYSIS In world space, rectilinear coordinates with reference to the basic Cartesian system are used to define the position of the end-effector. Usually the origin of the Cartesian axes is located in the robot's base. – VW = (x, y) where VW refers to the position of the endeffector in world space. 2004 93 ROBOT MOTION ANALYSIS • The transformation of coordinates of the end-effector point from the joint space to the world space is known as forward kinematic transformation. • Similarly, the transformation of coordinates from world space to joint space is known as backward or reverse kinematic transformation. 2004 94 Forward KinematicTransformation LL Robot: Let us consider a Cartesian LL robot J 1( x 1 , y1) y L 2 J 2 ( x 2 ,y 2 ) L ( x , L 3 Joints J1 and J2 are linear joints with links of variable lengths L1 and L2. Let joint J1 be denoted by (x1 y1) and joint J2 by (x2, y2). From geometry, we can easily get the following: y ) x2=x1+L2 1 y2 = y1 x 2004 95 Forward KinematicTransformation These relations can be represented in homogeneous matrix form: x2 1 0 L2 x1 y2 0 1 0 y1 1 0 0 1 1 or 2004 X2=T1 X1 96 Forward KinematicTransformation where x2 X2 y 2 1 1 0 L2 T1 0 1 0 0 0 1 x1 X1y1 1 If the end-effector point is denoted by (x, y), then: x = x2 y = y2 - L3 2004 97 Forward KinematicTransformation therefore: x 1 0 0 x2 y 0 1 L2 y2 1 0 0 1 1 X = T2 X2 or and 2004 TLL = T2 T1 1 0 L2 TLL 0 1 L 0 0 1 98 Forward KinematicTransformation RR Robot: Let q and a be the rotations at joints J1 and J2 respectively. Let J1 and J2 have the coordinates of (x1, y1) and (x2, y2), respectively. One can write the following from the geometry: x2 = x1+L2 cos(q) y2 = y1 +L2 sin(q) 2004 99 Forward KinematicTransformation In matrix form: x2 1 0 L2 cos(q) x1 y2 0 1 L2 sin(q) y1 1 1 1 0 0 or X2 = T1 X1 On the other end: x = x2 +L3 cos(a-q) y = y2 - L3 sin(a-q) 2004 100 Forward KinematicTransformation In matrix form: x 1 0 L2 cos(a q) x2 y 0 1 L2 sin(a q) y2 1 1 0 0 1 or X = T2 X2 Combining the two equation gives: X = T2 (T1 X1) = TRR X1 2004 101 Forward KinematicTransformation where TRR = T2 T1 1 0 L2 cos(q) L2 cos(a q) TRR 0 1 L2 sin(q) L2 sin(a q) 1 0 0 2004 102 Forward KinematicTransformation TL Robot: Let a be the rotation at twisting joint J1 and L2 be the variable link length at linear joint J2. z J 2 ( x 2 y y 2 ) One can write that: ( x L J1 ( x 1 y ) x = x2 + L2 cos(a) 2 y 1 ) y = y2 + L2 sin(a) x 2004 103 Forward KinematicTransformation In matrix form: x 1 0 L2 cos(a) x2 y 0 1 L2 sin(a) y2 1 1 0 0 1 or X = TTL X2 2004 104 Backward Kinematic Transformation LL Robot: In backward kinematic transformation, the objective is to drive the variable link lengths from the known position of the end effector in world space. x = x1 + L2 y = y1 - L3 y1 = y2 By combining above equations, one can get: L2 = x - x1 L3 = -y +y2 2004 105 Backward Kinematic Transformation RR Robot: x = x1 + L2 cos(q) + L3 cos(a-q) y = y1 + L2 sin(q) - L3 sin(a-q) 2004 106 Backward Kinematic Transformation One can easily get the angles: x - x y y L L cos (a ) = 2 1 2 1 2 2 2 3 2 L 2 L3 and y - y1 L2 L3 cos(a ) x x1 L3 sin( a ) tan(q ) = x - x1 L2 L3 cos(a ) y y1 L3 sin( a ) 2004 107 Backward Kinematic Transformation TL Robot: x = x2 + L cos(a) y = y2 +L sin(a) One can easily get the equations for length and angle: L= x - x 2 y y 2 2 2 and y - y2 sin(a) = L 2004 108 EXAMPLE An LL robot has two links of variable length. Assuming that the origin of the global coordinate system is defined at joint J1, determine the following: a)The coordinate of the end-effector point if the variable link lengths are 3m and 5 m. b) Variable link lengths if the end-effector is located at (3, 5). 2004 109 EXAMPLE J 1( 0 , 0 ) x L 2 = 3 m J 2 ( x 2 ,y 2 ) L ( x , L = 3 5 m y ) 1 y 2004 110 EXAMPLE Solution: a) It is given that: (x1, y1) = (0, 0) 1 0 L2 TLL 0 1 L3 0 0 1 1 0 3 TLL 0 1 5 0 0 1 x x1 y TLLy1 1 1 Therefore the endeffector point is given by (3, -5). x 1 0 3 0 y 0 1 50 1 0 0 1 1 x 3 y 5 1 1 2004 111 EXAMPLE b) The end effector point is given by (3, 5) Then: L2 = x - x1 = 3 - 0 = 3 m L3 = -y + y1 = -5 + 0 = -5 m ( 3 , L The variable lengths are 3 m and 5 m. The minus sign is due to the coordinate system used. J 1( 0 , 0 ) 5 ) 3 L 2 x J 2 ( x 2 ,y 2 ) L 1 y 2004 112 EXAMPLE An RR robot has two links of length 1 m. Assume that the origin of the global coordinate system is at J1. a) Determine the coordinate of the end-effector point if the joint rotations are 30o at both joints. b) Determine joint rotations if the end-effector is located at (1, 0) 2004 113 EXAMPLE It is given that (x1, y1) = (0, 0) 1 0 L2 cos(q) L2 cos(a q) TRR 0 1 L2 sin(q) L2 sin(a q) 1 0 0 Therefore the end-effector point is given by (1.8667, 0.5) 1 0 3 1 2 TRR 0 1 1 0 2 0 0 1 x x1 y = TRRy1 1 1 x 1 0 18667 . 0 y 0 1 0.5 0 1 1 1 0 0 x 18667 . y 0.5 1 0.51 2004 114 EXAMPLE 2004 115 EXAMPLE It is given that (x, y) = (1, 0), therefore, x 2 y 2 L22 L23 cos(a ) = 2 L3 L2 12 0 2 12 12 cos(a ) = 0.5 2 x1x1 a = 120o 2004 116 EXAMPLE y - y1 L2 L3 cos(a ) x x1 L3 sin( a ) tan(q ) = x - x1 L2 L3 cos(a ) y y1 L3 sin( a ) 0 - 01 1x cos(120) 1 01 sin( 120) tan(q ) = 1 - 01 1cos(120) 0 01 sin( 120) 3 tan(q) = 2 = 3 0.5 q = 60o 2004 117 EXAMPLE In a TL robot, assume that the coordinate system is defined at joints J2. a) Determine the coordinates of the end-effector point if joint J1 twist by an angle of 30o and the variable link has a length of 1 m. b) Determine variable link length and angle of twist at J1 if the end-effector is located at (0.7071, 0.7071) 2004 118 EXAMPLE z J 2 ( 0 0 y ) ( x L J1 ( x 1 2 y = 1 y ) m 1 ) x 2004 119 EXAMPLE a) It is given that (x2, y2) = (0, 0); L = 1m and a = 30o 1 0 L2 cos(a ) TTL 0 1 L2 sin( a ) 0 0 1 2004 TTL 1 0 1 cos(30 o ) 0 1 1sin( 30 o ) 0 0 1 TTL 1 0 0.866 0 1 0.5 0 0 1 120 EXAMPLE x 1 0 0.866 0 y 0 1 0. 5 0 1 0 0 1 1 x 0.866 y 0. 5 1 1 (x, y) = (0.866, 0.5) 2004 121 EXAMPLE b)It is given that (x, y) = (0.7071, 0.7071) L = (x - x1 ) 2 ( y y1 ) 2 L = (0.7071 - 0) 2 (0.7071 0) 2 L 1m sin(a) = (y-y2)/L = (0.7071-0)/1 = 0.7071 a = 45o 2004 122 Where Used and Applied 2004 123 ROBOT APPLICATIONS Loading/unloading parts to/from the machines – The robot unloading parts from die-casting machines – The robot loading a raw hot billet into a die, holding it during forging and unloading it from the forging die – The robot loading sheet blanks into automatic presses – The robot unloading molded parts formed in injection molding machines – The robot loading raw blanks into NC machine tools and unloading the finished parts from the machines 2004 124 ROBOT APPLICATIONS Welding – Spot welding: Widest use is in the automotive industry – Arc welding: Ship building, aerospace, construction industries are among the many areas of application. Spray painting: Provides a consistency in paint quality. Widely used in automobile industry. Assembly: Electronic component assemblies and machine assemblies are two areas of application. Inspection 2004 125 ECONOMIC JUSTIFICATION OF ROBOTS Payback period method: net investment cost of the robot system including accesories n net annual cash flow n = number of years that the investment is paid back 2004 126 ECONOMIC JUSTIFICATION OF ROBOTS net investment cost = total investment cost of robot - investment tax credit 2004 127 ECONOMIC JUSTIFICATION OF ROBOTS net annual cash flow = annual anticipated revenues from robot installation including direct labor and material cost savings – annual operating costs including labor, material and maintenance costs of the robot system 2004 128 ECONOMIC JUSTIFICATION OF ROBOTS EXAMPLE: A company is planning to replace a manual painting system by a robotic system. The system is priced at $160,000 which includes sensors, grippers and other required accessories. The annual maintenance and operation cost of robot system on a single-shift basis is $10,000. The company is eligible for a $20,000 tax credit from the government under its technology investment program. The robot will replece two operators. The hourly rate of an operator is $20 including fringe benefits. There is no increase in production rate. Determine the payback period for one-shift and two-shift operations. 2004 129 ECONOMIC JUSTIFICATION OF ROBOTS Net investment cost = capital cost – tax credits Net investment cost = 160,000 [$]- 20,000 [$] = 140,000 [$] 2004 130 ECONOMIC JUSTIFICATION OF ROBOTS Annual labor cost = operator rate x number of operators x days per x hours per day Annual labor cost = 20 [$/hr] x 2 x 250 [d/yr] x 8 [hr/d] Annual labor cost = 80,000 [$/yr] (for a single shift) Annual labor cost = 160,000 [$/yr] (for a double shift) 2004 131 ECONOMIC JUSTIFICATION OF ROBOTS Annual saving = annual labor cost – annual maintenance and operating cost Annual saving = 80,000 [$/yr] - 10,000 [$/yr] = $70,000 [$/yr] (for a single shift) Annual saving = 160,000 [$/yr] - 20,000 [$/yr] = $140,000 [$/yr] (for a double shift) 2004 132 ECONOMIC JUSTIFICATION OF ROBOTS for a single shift: Payback period = 140,000 [$] / 70,000 [$/yr] = 2 [yr] for a double shift: Payback period = 140,000 [$] / 140,000 [$/yr] = 1 [yr] 2004 133 ECONOMIC JUSTIFICATION OF ROBOTS EXAMPLE: • Compute the cycle time and production rate for a single machine robotic cell for an 8 hour shift if the system availability is 90%. Also determine the percent utilization of machine and robot. • Machine processing time 30 s • Robot picks up the part from the conveyor 3.0 s • Robot moves the part to the machine 1.3 s • Robot loads the part on to the machine 1.0 s • Robot unloads the part from the machine 0.7 s • Robot moves the part to the conveyor 1.5 s • Robot puts the part on to the outgoing • conveyor 0.5 s • Robot moves from the output conveyor • to the input conveyor 4.0 s • 2004 Total 12 s 134 ECONOMIC JUSTIFICATION OF ROBOTS Solution: • The total cycle time: 30 + 12 = 42 s Production rate: • (1/42) part/s 3600 s/hr 8 hr/shift 0.90 (uptime) • = 617 parts/shift Machine utilization: • Machine cycle time/total cycle time = 30/42 • = 71.4% Robot utilization: • robot cycle time/total cycle time : 12/42 • = 28.6% 2004 135 Advantages • Greater flexibility, re-programmability • Greater response time to inputs than humans • Improved product quality • Maximize capital intensive equipment in multiple work shifts • Accident reduction • Reduction of hazardous exposure for human workers • Automation less susceptible to work stoppages 2004 136 Disadvantages •Replacement of human labor • Greater unemployment • Significant retraining costs users of new technology for both unemployed and • Advertised technology does not always disclose some of the hidden disadvantages • Hidden costs because of the associated technology that must be purchased and integrated into a functioning cell. Typically, a functioning cell will cost 3-10 times the cost of the robot. 2004 137 Limitations •Assembly dexterity does not match that of human beings, particularly where eye-hand coordination required. • Payload to robot weight ratio is poor, often less than 5%. • Robot structural configuration may limit joint movement. • Work volumes can be constrained tooling/sensors added to the robot. by parts or • Robot repeatability/accuracy can constrain the range of potential applications. 2004 138 ROBOT SELECTION In a survey published in 1986, it is stated that there are 676 robot models available in the market. Once the application is selected, which is the prime objective, a suitable robot should be chosen from the many commercial robots available in the market. 2004 139 ROBOT SELECTION The characteristics of robots generally considered in a selection process include: Size of class Degrees of freedom Velocity Drive type Control mode Repeatability Lift capacity Right-left traverse Up-down traverse In-out traverse Yaw Pitch Roll Weight of the robot 2004 140 ROBOT SELECTION 1. Size of class: The size of the robot is given by the maximum dimension (x) of the robot work envelope. Micro (x < 1 m) Small (1 m < x < 2 m) Medium (2 < x < 5 m) Large (x > 5 m) 2. Degrees of freedom. The cost of the robot increases with the number of degrees of freedom. Six degrees of freedom is suitable for most works. 2004 141 ROBOT SELECTION 3. Velocity: Velocity consideration is effected by the robot’s arm structure. Rectangular Cylindrical Spherical Articulated 4. Drive type: Hydraulic Electric Pneumatic 2004 142 ROBOT SELECTION 5. Control mode: Point-to-point control(PTP) Continuous path control(CP) Controlled path control 6. Lift capacity: 0-5 kg 5-20 kg 20-40 kg and so forth 2004 143