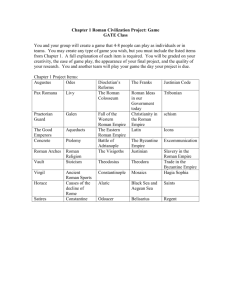

Styles, ages, life I

advertisement

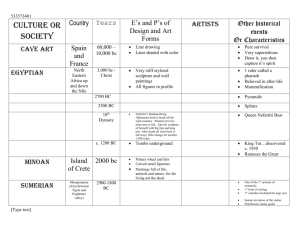

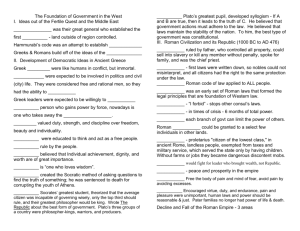

Styles ages life 1 from Paleolithic untill preRomanesque Period Radovan Ivančević Paleolithic art is an art of a hunter. In this, very cold period, you could say that a man lives of an animal: it provides him with meat for nourishment, fur for clothes, even bones to make tools ( blades, needles or fishhooks). He sometimes carves the characters or figures in the bones. The visual arts of the Paleolithic Period, cave paintings, knows only one theme: animals. The Old Stone Age, or Paleolithic ( from Greek , ''old'', and lithos ''stone'') is an age in which hunting is the main human occupation, so it is natural that animals are the main theme of his art. In the very beginning of visual arts, we conclude that even the choosing the theme has its profound meaning. There was nothing other than nature in that time, as oppose from today, where human architectural works dominates over nature. There are thousands of preserved cave paintings of animals found throughout Europe: From Spain to Russia. However, human or landscape paintings are basically non existent ( with some exceptions). The caveman's art theme is a theme of his life. While still in an Ice Age, human life directly depended on animals. His destiny was deeply intertwined with bigger and stronger animals and wild beasts, for if he had not succeeded in killing them, they could just as easily have killed him. In the Mesolithic Period,though often neglected in historical overviews, three great changes of vital importance for the visual arts occured. Cave paintings, as in the Paleolithic Period, are predominant, however the themes are more diverse , and, more importantly, human figures are depicted for the first time. There are also changes in the picture design, the pictures are not so realistic, the details are left out and human figures are highly stylized, they are depicted more like pictographs (signs). Paintings of the Mesolithic Period contained composition. This latest novelty was tremendously important discovery in art history. From that point onward, composition in paintings will be used very often. The appearance of composition tells us that some vital changes influenced human life. The Mesolithic Period is an age when people started living together in more organized communities. In other words, first societies began to form in the Mesolithic. Humans can now build their own habitats, rather than being dependent on natural shelters. Human civilization saw the appearance of arhitecture for the first time in the Neolithic Period. A man can now build a shelter in an area suitable for farming or close to the source of water, in that way creating first settlements. He builds huts, cottages and shacks. Soil will help people in construction; they will cover their houses made of branches, wood and logs with clay to protect them from from cold or drafts. People's independence from nature can be simbolically represented with an another inovations, such as pottery, baked clay and ceramics. Mesopotamia Modern archeology of the 20th century proved that the Tower of Babel, as mentioned in the Bible, was a foursided brick pyramid seven storeys, steps or terraces high. Try to imagine this vast monument, called the ziggurat by the Babilonians, in an endless plain of Mesopotamia, rising above the horizon like a clay mountain. With its seven steps, the ziggurat looked just like a stairway. Knowing that, it is easy to comprehend the beliefs of common, uneducated people that this building was created to connect the Earth with the Sky. A temple was built on top of the ziggurat, in which the priests worshiped the gods. It was also believed that the temple was used by the king to receive laws directly from God, ensuring the king absolute power in the land. King Hammurabi was depicted in such manner receiving commandments from Ahura Mazda, a supreme deity, on a stone stele carved in relief. On this large piece of stone the Code of Hammurabi, the oldest set of laws in the world, was engraved in cuneiform script. However, this was not the only one Tower of Babel, just as Babylon was not the only city in Mesopotamia. There were several cities in between Euphrates and Tigris and every larger one had its own ziggurat. Ancient Greece town There were two most important centres of social life in Ancient Greece cities: agora was the social, political and cultural center of the city and acropolis used for religious purposes. Furthermore, there were two structures very significant for understanding ancient Greek culture; stadium and the theatre. The first one was used for spiritual uplifting of citizens, and the latter for their physical development. These two buildings are the symbols of a well known ancient Greek aphorism: a sound mind in a sound body. This proverb was taken over by the Romans and in Latin it spells: mens sana in corpore sano. It signifies a everlasting aspiration of the Greeks to achieve harmony in their life. Agora is a public space made for all citizens, very similar to contemporary market places or city squares. However, present day cities have numerous squares with different purposes or features, while in ancient Greece there was only one center of political, social and business life. In older times this was the gathering place for principal assembly, and in the following years this was the center of all political bodies. The temples in ancient Greek cities were predominantly built on a sacred area. The most famous and most grandious of them was the Acropolis of Athens (meaning ''Upper City'', derived from acron, ''edge, extremity,'' and polis ''city''). It was located on a steep , in some places almost vertical, rocky hill. The hilltop is stretched (300x150 m) and several irregular, better yet freely arranged temples has been built on it. On the highest point of this space, right along its right edge, lies the Parthenon, the biggest and most important shrine of Athens, dedicated to goddess Athena, whom the Athenians regarded as their patron. It is a rectangular building, elevated on a platform three steps from the ground, and surrounded by columns (peripteral), carrying stone blocks (architrave). Above the blocks is a frieze of carved pictorial panels (metopes), separated by vertically channeled tablets (triglyphs), with a crest and dual-pitched roof at both ends, (see more for architecture: Doric order). On the opposite side of the Parthenon, along the outer rim of the hilltop, lies the temple of Erechtheion. It consists of three diverse and differently positioned structures, each with its own facades. The architraves are supported with columns except one structure, in which six female figures are placed instead of columns. Human sculptures that support the architrave instead of columns are called caryatids. With its multiple adjacent structures, each of them unique and pointed in different directions, this small temple of unified proportions may serve as a model for the individual and free spirit of ancient Greek art. Ancient Greek sculpture The Archaic Period (Greek archaiko meaning ''primitive,old'') marks the beginning of the majestic stone sculpture on the Greek peninsula and surrounding islands. The forms are simple and as if bound into the main body of a sculpture. Female figures ( kore) are standing and clothed in long drapes with thin engraved wrinkles, similiar to fluttering in columns, while the male figures (kouros) are standing solidly on one leg with the other one slightly bent. Their arms are layed down resembling to stiff Egyptian statues. Their heads are well rounded, and the details such as eyes, nose,hair, ears, are slightly lifted from the face. Hair and beards are shaped with thin incisions, paralel curved lines or spiral curls, properly and evenly as if an ornament, not a live hair. There were many traces of paint on the sculptures so we know that they were painted with bright and lively colors. The paint was washed down with rain, and bleeched by sun over time, so we recognize them as stone or marble white. Classic Greek Sculpturee Classic Greek sculpture is characterized by ideal proportions of parts and size of the human body. It is known that the sculptors had rules (Canons) concerning size ratios of parts of human body towards themselves and toward the whole body. The simplest way of depicting it was in proportion of the head to the rest of the body. In the archaic Period it was 1:5 (that is to say the body had to be exatly five times taller than the head), as it is shown on the sculptures of Polykleitos, for example in his sculpture Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer). In the Classic Period the ratio was changed to 1:6, which means the body was leaner, or the head became smaller and more elegant, as in the sculptures of Praxiteles, such as Hermes and the infant Dionysus. The same can be said for the reliefs, of which the clearest example are the reliefs of metopes on Parthenon, carved in high relief by Phidias. He carved both classicaly elegant and calm sculptures on the triangular gable of the temple (tympanum). The sculpture of the Hellenistic Period is most recognizable by the restlessness that breaks out of it, whether from its unclear composition, or from its emphasized movements, or even from the moulding the sculptor creates with powerful and deeply intertwined parts. These parts make the light on the sculpture break on the visible parts, and the ones in the shadow, making the sculpture seem to be in constant struggle between light and shadow, increasing the passion and excitement conveyed to the spectator. A clear example is the Winged Victor of Samothrace also known as Nika of Samothrace. Ancient Roman Urbanism In the Europe of prehistoric communities, Roman cities were systematically built and large in perspective. It was a rectangular space fortified and surrounded with walls and towers. Inside the fortification the main streets cardo and decumanus were intersected under the right angle (the first was shorter, north-south oriented and the latter was longer and positioned in east-west direction). Every street was parallel with one of the main streets and were built with precise spacing between them so that they formed a square grid for pedestrian and roadway traffic. Residental quarters between the streets were like islands, so the Romans called them accordingly: an insula. No matter how far away from Rome or on what stage of prehistoric development the surrounding rural tribes may be, each of the newly built Roman city had all the characteristics of a fully developed urban way of life. The streets were paved with flag stones, while the multi storey apartment blocks were built out of stone or brick. Each town had a theatre and the arena (amphiteatre) for larger spectacles. The town square (forum) was often surrounded with columned porch. There was the main temple (templum) of the city located on the square, while the marketplace, stores and artisan shops (tabernae) were all around the main square. Also, there was a town court house (basilica) on the main square along with several other important state and town buildings. Beside the square, the main gathering place of Roman citizens was the thermae, a public facilities for bathing. With hot,warm and cold water pools ( caldarium, tepidarium, frigidarium), the thermae had also rooms for physical exercise and reading. Roman Art There were two, very different, even contradictory phases in Roman art, Classic Roman art of the 1st and 2nd century AD, and Late Antiquity of 3rd and 4th century AD. Early Christian Art Early Christian Art is basically a part of Roman art, only that some new figures, scenes and symbols were introduced. The beginnings of Early Christian Art are set in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th century AD, in a time when Christians were still prosecuted. It continues on, in a slightly different form, even after Christianity was supported by the state and made the offical religion of the Roman Empire during the reign of Emperor Constantine I in 313 AD. After Christianity became publicly acknowledged the Christians communities started building specific structures or churches for perfoming rituals.They were basilicas in form, a structure widely known in the pagan times of Roman Empire, used then as a court house. It was a prolonged squared building, separated with two sets of columns connected to one another with arches (arcades). The columns divide three naves, the central one being higher and twice as long as oppose to side naves. Windows were built in the upper parts of the middle nave walls, providing direct sunlight to the central space. Opposing the entrance, a semicircular stone bench was placed for judges. It could have been set in a semicircular recess or the apse. The most important structure of the christian cult (after basilicas) was the baptistery. Its purpose can be clearly seen from its form. However, in order to understand its appearance we must know that in the days of early Christianity only adults were subjected to baptism, after they had learned the Christian doctrine, unlike today's practice of baptisting newborn babies. Hence large pools were used to baptise people instead of baptising wells or holy water bowls. Adults would be wrapped in white sheets and then entered the water neck-deep, with occasional diving of the whole body. Simbolically, baptism ceremony represented washing off sins from the whole body. Early Christian basilicas had a specific room, often on the north side, that was designed for the people wanting to become Christians (catechumens) to study the Christian religion (similar to contemporary catechism). Alongside this room, there was a smaller centerpiece structure, somewhere squared, hexagon or octagonal, with the interior space centered around a baptismal font, usually cross shaped. Three steps were leading into the font from one of the lines of the cross, while the other lines three catechumens could be placed. Early Byzantine art After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Emperor Justinian of the Byzantine Empire, at the time very powerful with strong, organized army, decided to reclaim and reunite the Empire as it had been before the fragmention in the 4th century AD. By the beginning of the 6th century AD Justinian embarked on this military march (in Latin called the reconquista meaning ''retaking'') and slowly, one by one, cities fell and new governance was set up incorporating them in the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantine Empire. The largest cities such as Salona, Zadar (Iadera), Osor (Apsarum), Pula (Pola), Poreč (Parentium) and Trieste, in the eastern coast of the Adriatic were included in the new Empire in this way, while the new Exarchate of Ravenna was founded, with Ravenna, positioned on the west coast, becoming the administrative center on the Adriatic. After the liberation, Justinian built new cities restlessly all around the Empire, so the age under Justinian rule in art history is called the Age of Justinian, the first golden age of Byzantine art. He developed a type of a large dome church, the biggest one of them for centuries was Hagia Sofia (dedicated to the Wisdom of God) in Constantinople. Hagia Sofia was built with one monumental dome caried on with two semi-domes. Large churches from this era include St. Irene's church in Constantinople, St. Sergius and Bacchus in Thessaloniki and many others. These churches and churches alike will set an example for a typical Byzantine type church in the next 800 years (up untill the fall of Constantinople to Ottoman Empire) with a rounded center beneath a dome, unlike longitudinal three part basilicas, whic was the basic form of a church in the West. There were two other, equally longlasting, features of Byzantine architecture: exclusive brick building (as oppose to typical stone building in Europe) and depicting iconographic representations solely via paininting techniques (mosaics and murals) without sculptures (immensely important in West-European sacral architecture in Romanesque and Gothic Art). Several churches and baptisteries on the Eastern Adriatic Coast are worth mentioning. A great cross shaped bishop church and a new octogonal baptistery, modeled after the Diocletian mausoleum, was built in Salona. The cathedral in Pula was rebuilt, and almost completely new cathedral was built in Poreč.