Set 1

advertisement

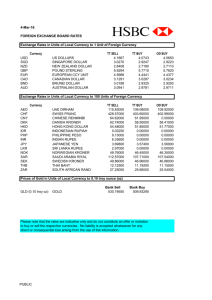

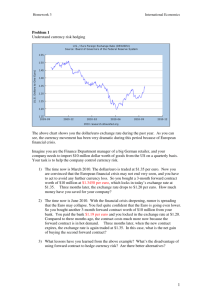

Econ 141 Fall 2013 Slide Set 1 Introduction to exchange rates and exchange rate regimes Defining the Exchange Rate • The exchange rate is the price of a unit of one currency in terms of another currency. • For example, the U.S. dollar exchange rate for euros is E$/€ =dollars/one euro This is currently E$/€ = 1.35 dollars per euro. The euro exchange rate for U.S. dollars is E€/$ = 0.74 euros per dollar E$/¥ = 0.0102 dollars per yen and E¥/$ = 98.08 yen per dollar E$/£ = 1.62 dollars per pound and E£/$ = 0.62 dollars per pound Defining the Exchange Rate • Notice that E$/€ 1 = E €/$ 1 1.35 = 0.74 • We need to be explicit about how we are expressing the relative price of one currency in terms of the other. • We will use the convention that we express exchange rates as the number of units of the home currency that exchange for one unit of foreign. Appreciations and Depreciations • If one currency buys more of another currency, we say it has experienced an appreciation – its value has risen, appreciated or strengthened. • If a currency buys less of another currency, we say it has experienced a depreciation – its value has fallen, depreciated, or weakened. Appreciations and Depreciations • For the U.S. dollar, When the U.S. exchange rate E$/€ rises, more dollars are needed to buy one euro. The price of one euro goes up in dollar terms, and the U.S. dollar experiences a depreciation. When the U.S. exchange rate E$/€ falls, fewer dollars are needed to buy one euro. The price of one euro goes down in dollar terms, and the U.S. dollar experiences an appreciation. Appreciations and Depreciations Similarly, for the euro, When the Eurozone exchange rate E€/$ rises, the price of one dollar goes up in euro terms and the euro experiences a depreciation. When the Eurozone exchange rate E€/$ falls, the price of one dollar goes down in euro terms and the euro experiences an appreciation. Appreciations and Depreciations • At the beginning of January 2011, the dollar value of the euro was E$/€ =1.32 • At the beginning of May 2011, it was E$/€ =1.47 • Over this period, the dollar depreciated against the euro by the amount ∆E$/€ = 1.47 - 1.32 = 0.15 • The percentage depreciation was ∆E$/€/ E$/€ x 100 = (0.15 / 1.32) x 100 = 11% The annual rate of depreciation over these four months was 38%. Multilateral Exchange Rates • To aggregate different trends in bilateral exchange rates into one measure, we can calculate multilateral exchange rate changes for baskets of currencies using trade weights to construct an average of all the bilateral changes for each currency in the basket. • The resulting measure is called the change in the effective exchange rate. Eeffective E1 Trade 1 E2 Trade 2 EN Trade N Eeffective E1 Trade E2 Trade E N Trade Trade - weightedaverage of bilateral nominal exchange rate changes Exchange rates and relative prices of goods. • Suppose you wanted to buy a Belgian chocolate bar selling for 1 euro: The cost of the bar in dollars will be 1 euro x E$/€ dollars/euro. On Jan 2, 2011, it would cost $1.32 But on May 1, 2011, you would pay $1.47 • Suppose BMW sold a car in L.A. for $35,000 in 2011. Once it exchanged its receipts to euros, BMW would receive €26,515 in January but only €23,810 in May. Changes in the exchange rate cause changes in prices of foreign goods expressed in the home currency. Changes in the exchange rate cause changes in the relative prices of goods produced in the home and foreign countries. When the home country’s exchange rate depreciates, home exports become less expensive as imports to foreigners, and foreign exports become more expensive as imports to home residents. When the home country’s exchange rate appreciates, home export goods become more expensive as imports to foreigners, and foreign export goods become less expensive as imports to home residents. Exchange Rate Regimes: Fixed Versus Floating • Fixed (or pegged) exchange rate regimes are those in which a country’s exchange rate fluctuates in a narrow range (or not at all) against some base currency over a sustained period, usually a year or longer. A country’s exchange rate can remain rigidly fixed for long periods only if the government intervenes in the foreign exchange market in one or both countries. • Floating (or flexible) exchange rate regimes are those in which a country’s exchange rate fluctuates in a wider range, and the government makes no attempt to fix it against any base currency. Appreciations and depreciations may occur from year to year, each month, by the day, or every minute. Floating exchange rates • The major currencies of the world, float against one another. For example, the U.S. dollar is allowed to float against the euro, the pound, the yen, as well as many smaller country currencies (for example, the Danish krone, Canadian dollar (loonie) or New Zealand dollar (kiwi)). Developing Country Exchange Rates • Exchange rates in developing countries can be much more volatile than those in developed countries. • India is an example of a middle ground, somewhere between a fixed rate and a free float, called a managed float (also known as dirty float, or a policy of limited flexibility. • Dramatic depreciations, such as those of Thailand and South Korea in 1997, are called exchange rate crises and they are more common in developing countries than in developed countries. Green line shows a measure volatility of the exchange rate. Currency Unions and Dollarization • Under a currency union (or monetary union), there is some form of transnational structure such as a single central bank or monetary authority that is accountable to the member nations. The most prominent example of a currency union is the Eurozone. • Under dollarization one country unilaterally adopts the currency of another country. The reasons for this choice can vary. A small size, poor record of managing monetary affairs, or if people simply stop using the national currency and switch en masse to an alternative. Exchange Rate Regimes • Independently Floating: 25 Countries • Including the U.S., Canada, Australia, Mexico, United Kingdom, Sweden, South Korea and even Albania. • Managed Floating: 44 countries • Including India, Singapore, Thailand and Kenya (many Latin American, East Asian and African countries) • Crawling bands or pegs: 10 countries • Including China Exchange Rate Regimes • Currency boards: 7 countries • Including Hong Kong • Other pegs: 60 countries • Including Argentina and many Central Asian and African countries • No independent currency: 46 countries • • • • The Eurozone The Central African and Western African CFA Franc Zones Eastern Caribbean Currency Union Use another currency: Ecuador, Panama, El Salvador and 7 others (7 use USD)