The Nature of the Teen Movie as a Form of

advertisement

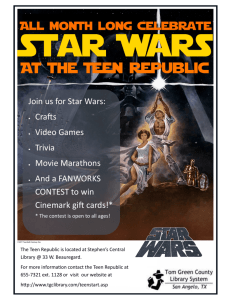

The Nature of the Teen Movie as a Form of Popular Culture The teen movie, or 'teenpic', is a genre which exploits the teenage market as a mass audience. Variously described as 'whimsical, ephemeral and pervasive' (Martin 1994, 65), this is not a strict, enclosed genre. Ideas of what constitutes a popular culture are continually changing. In this case, the nature of the teen movie genre changes very rapidly over time and there are crossovers with neighbouring genres, for example, horror ("Buffy, the Vampire Slayer"), sports ("American Anthem"), musicals ("Grease") and romance ("Romeo and Juliet"). James Fenlon Finley (1957), writing in 'Catholic World', expressed his concern that the public faced the prospect of the movie-makers 'getting hungry enough to start indulging the banal, untrained, irresponsible tastes of the average teenager'. Finley's comments were inspired by the success the year before of Sam Katzman's film "Rock Around the Clock". Teen movies typically contain features such as conversations at the school lockers ("Dazed and Confused"), the prom ("Carrie") cheerleaders ("Porky's"), the shopping mall ("Mall Rats") the juvenile delinquent gang ("Rebel without a Cause") and the sensitive, alienated teenage hero (Jim, in "Rebel"). Of course, the main characters of teen movies are often older than teenage (eg. "Wayne's World"). A better interpretation of 'teen' is 'youth'. French film critic Robert Benayoun once described the 'normal qualities of youth as naively, idealism, humour, hatred of tradition, erotomania (abnormally strong sexual desire), and a sense of injustice' (Martin 1994, 67). This description is very true to the teen movie, because it points to the two poles of the genre (Martin 1994), that is, at the one end, the craziness characterised by freeforall fun, sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll, and at the other end, the equally important innocence, uncomplicated contact with another human being, and the unformed, impossible dream of a better world tomorrow (hopeless teenage optimism) (eg. Francis Ford Coppola's "The Outsiders"). Teen movies usually contain the magic teen formula, offered by Alan Alda, of 'destruction of property, defiance of authority and removal of clothes.' These two extremes of teenpics are found within the same film. Even a wild romp like "Porky's" end with a social conscience and a moral platform, while an uplifting teen drama like "Stand By Me" is likely to have a scene where a grossly fat boy barfs all over his parents and teachers. The stories of most teenpics are about what theorists call 'the liminal experience' (Martin 1994, 68), that is that intense, suspended moment between yesterday and tomorrow, between childhood and adulthood, between being a nobody and a somebody, when everything is in question, and anything is possible. Importantly, for a teenager, the liminal experience does not feel like a passing phase; it is a complete and significant moment. There, lurking in the background are Pete Townsend's legendary words, penned in the Sixties, 'hope I die before I get old', suggesting a frozen teenage time, a time when the teen movie genre 'keeps fa7`ls in the mad thrall of an eternal, delinquent, vacuous youth' (Martin 1994, 64). Finally, it is worth noting the ongoing relationship between teen movies and mass culture (see 'The Contribution of Popular Culture to Social Change). Belton (1966) wrote that 'if films and filmmakers produce culture, they are also produced by it. The movies are inseparable from the society within which they exist; one does not produce the other; rather, each interacts with the other and they mutually determine one another'. The Creation of the Teen Movie as Popular Culture The teenpic began around 1956 with the rise of the privileged American teenager. In that year, Sam Katzman made "Rock Around the Clock". Its success showed the 'present power and future ascendancy of the teenage moviegoer' (Doherty 1988,14). This was the first hugely successful film marketed to teenagers 'to the pointed exclusion of their elders' (Doherty 1988, 74). After this, the Hollywood movie industry embarked on a campaign to attract and exploit teenagers, thus giving rise to a new genre, the teen movie. So, the beginning of this form of popular culture is due to three factors: 1. The emergence of teenagers as a social group distinct from adults, who had disposable income and different consumer desires. 2. The catalyst of Sarn Katzman's idea for a movie, Rock Around the Clock to exploit this new social group. 3. The collective decision of the 'Hollywood machine' to further pursue this exploitation, ie. to juvenilize movies. Because of the controversy over rock 'n' roll music, that is, its reputed connection to violence and juvenile delinquency, some screenings of "Rock Around the Clock" and another film, "Blackboard Jungle", featured incidents of disorder. Soon after the release of "Rock Around the Clock", Variety magazine warned: 'Rock 'n' roll - the most explosive show biz phenomenon of the decade may be getting too hot to handle. While its money-making potential has made it all but irresistible, its Svengali grip on the teenagers has produced a staggering wave of juvenile violence and mayhem.' American movie theatres were caught between a 'desire for teenage dollars and dread for teenage violence' (Doherty 1988, 102). This underlined the emerging division and distinction between teenagers and adults in society, and, therefore, the justification for the existence of the teen movie as a marketable item and as a significant aspect of popular culture. There was also a crossover between the teen movie and pop music industries. Alan Freed, a famous disc jockey and entrepreneur of the Fifties, began the practice of the 'tie-in'. He publicised teen movies by playing their songs on his radio show and used rock 'n' roll teenpics as 'warm-ups' at live concerts. Elvis Presley, who introduced rock 'n' roll to white youth, had made three teen movies by the end of 1957: "Love Me Tender", "Loving You", and "Jailhouse Rock". All three pictures were in the top twenty list, and all featured top-selling songs. In fact, the movies' titles were also song titles. The popular culture of teen movies is transmitted through marketing, promotion and distribution by the motion picture industry. This includes film production corporations, such as Warner Bros. and United Artists, who own and operate studios, distribution corporations like Hoyts and Greater Union in Australia, who also own and operate movie theatres, and independent operators, such as the Valhalla in Glebe or the local suburban cinema. As most teen movies eventually are released on video, video distribution companies and retail/rental outlets, for example, Video Ezy, are a part of the transmission process too. Other forms of media assist with the transmission, including newspapers (eg. The Metro section of the Sydney Morning Herald), magazines (film magazines, like Variety, fanzines, Rolling Stone, Qmag, The Face, Who), and television (screenings of teen movies, advertising, and programmes with specific content about movies, like "The Movie Show" on SBS, or "Recovery" on the ABC). The transmission described above illustrates the movement of products and ideas associated with the teen movie genre on a local and a national scale. The networks of the major corporations involved are, of course, global in their extent, and, nowadays, a teen movie release occurs pretty much simultaneously around the planet. The breadth of distribution of such a movie outside Australia, America and Europe depends on the degree of westernization in particular countries and the access of individuals to movie theatres and television. The existence of satellite TV and corporations like Rupert Murdoch's Sky Channel certainly facilitate the transmission of teenpic popular culture. Limiting factors may be the popularity of the local or national film genre (as in India), or censorship because of cultural mores and government intervention (as in Indonesia). One early example of the way in which the ideas and characters of a teen movie can be transmitted globally was the popularity of movie star James Dean outside America after the release of "Rebel without a Cause" in 1956. 'Of six thousand letters that arrive at Warner Brothers' Hollywood studios every month addressed to Jimmy Dean, over half come from abroad. In Sweden, 'Deanagers', dressed in the familiar jeans and jacket, have the police worried about their suicidal tactics on motor scooters. In Paris, thirty schoolgirls wrote to the manager of their local cinema asking him to change the dates of "Rebel" so that they could see it before they went away on holiday. He agreed. It was the fifteenth time the girls had seen the film' (Kureishi 1995, 60) Nowadays in Australia, Warner Bros Movie World 'offers the experience of Hollywood on the Gold Coast, an opportunity for Australians to immerse themselves in the culture of American popular cinema without going to Hollywood' (Turner 1994, 100). Movie World is both a 'movie magic' theme park and a real motion picture studio. Australian teen movie "The Delinquents" was produced there. Australians' visions of leisure, fashion, lifestyle and cultural identity has long been influenced by the diffusion of American ideas from the entertainment media, including the teenpic. The thirst for American input, together with the economic buying power and the crossover promotion with other forms of media, have all contributed to the growth of teen movies as a popular culture. Content analysis of teen movies from the 1950's through to the present reveals continuity in characteristics (as outlined in The Nature of Teen Movies, above), but there has been change in the specific detail of storylines, paralleling the movement from more conservative to less conservative censorship. An example of this is the increasing obviousness of erotomania in the action and dialogue of the movie. Of course, the language used may also reflect this change, as will the fashions. The teen movie also acts as a vehicle for transmitting other forms of popular culture, such as fashion, art, music and leisure pursuits, and these are constantly in update mode. The Consumers of Teen Movies as Popular Culture As stated earlier, the consumers of teen movies have been clearly identified as 'youth', including those actually in their teenage years. The movie industry, through 'demographic targeting and controversial and timely content' (Doherty 1988, 10), have ensured the continuity of this group as consumers. In addition, there may be a 'nostalgia factor', where adults who were, say, teenagers in the 1970's, may become consumers of a teen movie like "Dazed and Confused", produced in the 1990's but set in 1976, or Sixties teenagers who may be consumers of the film "Quadrophenia" (1980) because they were mods or rockers during that era. The Interactive Process Between Individuals and Aspects of Teen Movies As Popular Culture The content matter of teenpics may inspire consequent expression of personal ideas about popular culture, which may become evident through an individual's fashion sense, choice of magazine, or taste in pop music. The audiences at a teen movie like "Quadrophenia" were sometimes seen wearing parkas or 'zoot suits', as mods did. At a recent Australian screening of the Seventies teenpic, "Big Wednesday", a cult surf flick about three teenage surfers growing up in California, many people in the audience wore board shorts, zinc cream, lifesaver's caps and carried surfboards into the theatre. Many people can recall and recount teen movies, their plots, characters and music, and make a connection with seminal experiences in their lives, perhaps serious, perhaps humorous. A person who grew up in the country areas of Australia may relate closely to the characters and situations depicted in "The Year My Voice Broke", and, if they went away to boarding school, "Flirting" may be close to their hearts, while "Puberty Blues" will remind people of their teenage experiences in suburban beach culture. For school experiences, "The Breakfast Club" will bring back memories of interpersonal relationships with both fellow students and teachers, while "Dazed and Confused" will recall the emotions associated with leaving school and contemplating the future. Individuals' secondary socialisation continues through the medium of the teen movie. From characters and situations in a movie, a person learns, and may be influenced by, knowledge of: Behaviour (how does a teenager 'push the boundaries' of what's acceptable in the context of adult-determined norms?) Attitudes and values (what do teenagers think about other people, groups and issues; what is important in their lives?) Gender roles (how does a person express masculinity, femininity, sexuality?) Consider these ideas in relation to a teen movie you have seen recently. What socialisation influences can you note? As detailed earlier, hero figures as icons may also be an influence on the audience. (Consider what was written about James Dean in The Creation of Popular Culture section.) Who else would qualify to fit this description? Luke Perry, perhaps? Teenpics may also inspire fads, like singing 'Bohemian Rhapsody' all the time ("Wayne's World"), or wearing 'Beetle boots' and long-fringed hairstyles ("A Hard Day's Night"). Marketing paraphernalia has been a part of the teen movie industry, too, especially with regards to associated pop music and artists. To what extent can individuals influence teen movies as a popular culture? The answer to this question comes from an understanding that it is impossible to separate films and filmmakers from the society within which they exist. Teen movies and aspects of culture interact and mutually determine one another. (Belton 1996) So, while adolescents may be influenced by what they see in teenpics, in turn, a film maker's ideas may be inspired by the behaviour of the adolescents in his or her experience. Control of Teen Movies As Popular Culture By Groups, Institutions and Organisations Like its kindred spirit, rock 'n' roll, the teen movie is subject to some degree of control by groups, institutions and organisations. In 1956, a U.S. Senate Subcommittee, reporting on 'motion pictures and juvenile delinquency', made special mention of "Blackboard Jungle": 'The Committee feels there are valid reasons for concluding that the film will be a threat to the development of healthy young personalities' (Doherty 1988, 118). Censorship, then, by government (an institution) will have an influence on the specific nature of a teen movie's content. The filmmaker will stay within broadly 'acceptable' bounds, otherwise the teenpic will not be approved for release by studios and distributors. In addition, language, sexual references and violence will determine the government censor's classification (PG, M, MA, R) and therefore who can have access to the movie. Parents (the family - a group) may have control over whether or not their teenage children are allowed to watch particular movies, applying their own censorship values. An individual's peers (a group) may also have a controlling influence over which teenpics are 'cool' to see and which are not. Factors affecting this decision might include the relative conservatism of the group (not wanting to watch a movie containing sex scenes), the prevailing interests of the group (nobody is interested in surfing, so will not go to see a surf teenpic), ethnicity (teenpics produced in country of ancestry may be of greater interest), or gender and sexuality (teenpic storylines may appeal to a specific gender or sexual preference). Motion picture production corporations (organisations), as editors of ideas, scripts and visuals, have control over what the teen movie audience has access to watch. Censorship by groups and organisations can usually be described as unofficial, while censorship by institutions is official. Different Perceptions of Teen Movies as Popular Culture The characteristics of the teen movie genre described earlier help answer the question: 'who accepts this form of popular culture?'. Plainly, the mass youth audience targeted by producers of teenpics are accepting of the products released for their consumption. Box office success, in terms of tickets sold and revenue returned, is evidence of this. A 1968 survey by Daniel Yankelovich (Doherty 1988, 231) revealed that 48% of box office admissions were made up of the 16-24 age group, and that 54% of this group were 'frequent moviegoers'. Which teen movies will be accepted by which sections of the youth market will depend on the appeal of the storylines to various sub-cultures. Some will be of such general appeal that almost everyone will accept them. Comparisons can be made with the various categories of popular music and their consumer acceptance, ie. a new techno dance CD will be accepted by a narrower group than a new mainstream pop CD. As detailed earlier in this paper, rejection of teen movies mostly comes from the older generation, or authority groups, who disapprove of the subject matter and its consequent messages to young people regarding sex, drugs, general behaviour and attitude to authority. This rejection may be evidenced by censorship, refusing permission for children to attend, and, sometimes, protest, if an interest group such as the 'Call To Australia' Party feels sufficiently offended. Culture shock may be experienced by older people when they watch a teen movie, not only because of the nature of the story and behaviour of the characters, but also because of the slang, activities, music and ideas which exclude parents and others from understanding. The Contribution of Teen Movies to Social Change The aspects of adolescent western culture which are conveyed through the medium of the teen movie have contributed to the emergence and continuity of teenagers as a distinct subculture within the surrounding society (a significant piece of social change in itself). Prior to the 1950's, children simply transmorphed into adults, not displaying characteristics much different to their parents. Within the context of this relatively recently established social group, teen movies are constantly updating or introducing new ideas concerning attitudes, values, fashions, music and behaviour. The adolescent culture of James Dean's era, depicted in "Rebel Without a Cause", has similarities to the adolescent culture of today (the rebelliousness, for example), but describes a different world to the one illustrated in "Clueless", or "Buffy, the Vampire Slayer". On a broader scale, teenpics may raise consciousness about social issues like gender roles (Buffy) peer pressure (Black Rock) or drug abuse (Puberty Blues). The possibilities for contribution to social change in the future have been broadened by the development of the internet. Appendices to this paper show some of the information available to teen movie fans via web sites and home pages on the net. This includes reviews, fan club details, chat lines and marketing of paraphernalia. The consumers of today are able to form quite a different relationship with the producers, marketers and distributors of teenpics than was available to the consumers of earlier eras. Teen movies are a part of the social change associated with communication technology. Teen movies, like rock 'n' roll, 'fulfil the key criteria for popular culture'. (Howitt 1996) The genre is part of a constantly changing process. Various movies mean different things to different people. The movies of a particular era have served to unify the teenage subculture, then the genre has moved on to charm and unite the next generation, retaining its basic characteristics, but incorporating new aspects of popular culture. By Robin Julian Bibliography Belton J. 1996. Movies and Mass Culture. The Athlone Press, London.Doherty T. 1988. Teenagers and Teenpics. Unwin Hyrnan Ltd. London. Finley J. 1957. TV For Me. If Teens Rule Screens, in Catholic Weekly,Vol. 184. HowittB. 1996. Popular Culture. in Culture Scope, Vol. 55. Society and Culture Association, Sydney. Martin A. 1994. Phantasms: The dreams and Desires at the Heart of Our Popular Culture. Penguin, Ringwood (Victoria). Kureishi H 1995. The Faber Book of Pop. Faber and Faber, London. Tumer G. 1994. Making It National: Nationalism and Australian Popular Culture. Allen and Unwin, Sydney. Julian, R., Society and Culture Association, Teen Movies - a case study of a form of Popular culture, accessed July 19th, http://www.ptc.nsw.edu.au/scansw/teen.html#anchor147406