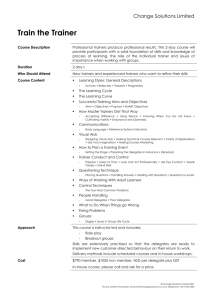

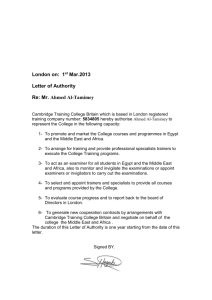

to the course outline - Cambridge training college britain

advertisement