I Want To Lose Weight - Virginia Review of Asian Studies

advertisement

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

I WANT TO LOSE WEIGHT: JAPANESE AND AMERICAN RESPONSES

TO OBESITY

VIRGINIA POPE

MARY BALDWIN COLLEGE

Abstract

Today over two-thirds of Americans are overweight, and one third of Americans are

obese. While Japan is often touted as having one of the smallest obesity rates in the

world, Japan operates on a modified Body Mass Index (BMI) scale. According to this

modified scale, just over a fifth of the population is obese. Both Americans and

Japanese are extremely concerned with their weight and seek ways to reduce it. This

has resulted in both cultures focusing on dieting and government policies. Both

Japan and America have developed “dieting cultures” that do little to actually

decrease the obesity rate, and potentially contribute to it. Each country has also

looked to political regulations to reign in the problem, but their actions to date will

likely create more ill health effects than they solve. Americans are becoming used to

larger sizes as normal, while simultaneously putting pressure on the population to

be normal or underweight. America has taken political action in the form of

educating children and has also debated the use of bans and taxes as a form of

consumption control. Japanese reject larger sizes despite the growing waistlines in

the country. In Japan, the pressure and the desire to be thin or underweight is

strongest for women under forty, which has contributed to the appearance of eating

disorders. The Japanese government has passed laws that state that those with a

waist measurement exceeding a certain number must receive diet and lifestyle reeducation courses. Until education about weight issues is improved in both

countries and society moves away from dieting culture, the obesity problem will

likely continue to grow.

Introduction

Growing up, my mother always had her nose in the latest dieting book. When I was in

elementary school, she was into the Zone diet. When I was in high school, she got into a diet that

dictated that you must eat your salad after your main course because it changes the way the food

is processed in the body. After my sophomore year at college, she decided she was going to go

on a gluten-free, starch-free and only-vegetables-for-carbs diet. My father would often get roped

into these diets as well, because my mother did all the cooking. My sister admits to being a yoyo

dieter and goes through periods of time when she adheres to a strict diet and exercise program,

only to at some point (usually around the holidays) break the diet and have to start all over again

after a few days to weeks off. My mother's sister moved after a divorce and decided that she was

going to lose weight and completely revamp her lifestyle. She cut out almost all meat, switched

to eating only vegan and homegrown foods, and limited herself to a small amount of

carbohydrates per day. She would only occasionally "splurge" with one item during the holidays,

87

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

and whenever she visited anyone she would bring her own food to eat.

When I traveled to Japan in 2008, I dropped three belt notches, despite being there for

only two weeks. My host mother at the time was incredibly happy for me and instructed me to

"continue losing weight". When I returned to Japan in 2012, I had expected a similar response

from my new host mother because my host father and sister were both on diets. My host father,

a Japanese men's size L, was working to lose his small "spare-tire", and my host sister just

seemed to be dieting to lose weight even though she was average sized. When I told my host

mother I went down a belt loop, she gave me a look of horror. It seemed that it was okay for me,

the guest, to remain obese by Japanese standards while her family dieted. I never saw my host

father eat a whole portion of a dessert, and he would lift what looked to be about 10 pound

weights before he took his bath each night. After seeing a segment on TV about how stretching

like a cat twenty times each night for a month could help you drop several kilograms, he added

that to his nightly routine. While my host sister would occasionally snack or eat a dessert with

me, she would often not eat her rice at dinner or shove portions of her food onto her mother's

plate. My host mother kept shoving cake at me when I got home from school, and I found myself

actively trying to limit my caloric intake at school so I wouldn't gain weight like my host mother

wanted.

All of these are stories of people trying to lose weight. Every family has one, and almost

every woman has a personal story to tell about dieting. Dieting has become so ingrained in our

culture today that it appears in almost every form of media. We have diet books; news outlets

occasionally give dieting advice; characters in movies and TV-shows often diet as

well. Whether the culture of interest is Japanese or American, it's hard to ignore dieting. Of the

above stories, only a few seemed to really be succeeding. My host father saw a small decrease in

weight over the time that I was there, but whether he will keep it off in the long run is something

I do not know. My family often succeeds at weight loss in the short term, but regains it in the

long run. Only my Aunt has seen any success in long-term weight loss, and it is for one major

reason: she does not really diet so much as the fact that she changed her diet.

The fact that both countries have giant dieting industries that have thrived for years, yet

waist lines continue to grow in each country alludes to a problem in the system. The fact that so

few ever see success in shedding excess weight in the long run also hints at problems. Japan and

America are both greatly concerned with the weight and health of their citizens, specifically the

obesity and overweight rates. Both countries are responding to these problems in different ways,

but neither are handling the problem in a way that will end with desired results, and may even

serve to worsen or create new health problems in the population.

Methodology

I have been collecting information for this research in various ways over the last two

years. Many of the sources I use to build my argument are psychological and sociological

studies, while others are studies carried out with the purpose of specifically looking at the obesity

rate or some factor related to it. The World Health Organization compiled the records of BMI

and calorie consumption across the world.

88

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

In the fall of 2012, I spent a semester in Japan. During this time I experienced the culture

first hand and was able to absorb a great deal through my everyday life. However, I felt this was

not enough and also conducted a questionnaire about dieting habits. 39 college-aged women

answered my questionnaire and the findings have been incorporated into this paper. When

possible, I have backed up my personal findings with previous research.

The Definition of Diet

There are two definitions for the word diet. Diet, used solely as a noun, means the food

that one consumes on a regular basis. If one eats eggs and bacon for breakfast, ham sandwiches

for lunch, and steak and potatoes for dinner every single day without change, then one's

diet consists of eggs, bacon, ham sandwiches, steak and potatoes. This is the diet that appears in

terms such as "the American diet", "the Mediterranean diet" and "the Japanese diet". "The

American diet" consists of foods that Americans regularly consume because the food is easily

accessible and does not fall within food taboos. For example, Americas eat beef but not crickets,

while other parts of the world exclude beef from their diet for religious reasons and others

include crickets because of their nutritional value.

The second definition of diet means to restrict calories in an effort to lose or maintain

weight. It is this diet that has corrupted terms like "the Mediterranean diet" from "the food

people in the Mediterranean region eat because it is plentiful and to their tastes" to "the food

people in the Mediterranean eat that keep them thin, so those in the rest of the world should try it

and lose weight". This second definition is also the one that the majority of people associate

with the word. It has become a word that many use every single day. However, for now I shall

focus on the first definition.

Definition of BMI

BMI stands for Body Mass Index and is a scale that measures body composition by

looking at a person's height and weight1. In the Western world, a BMI above 25 is considered

overweight, while a BMI of over 30 is considered obese.2 In much of Asia the scale is shifted to

recognize racial differences, with Japan's standard stating that 23 is overweight and 25 is obese.3

Across the globe, a BMI less than 18.5 is considered underweight. Any number that falls

between 18.5 and the overweight cut-off number is considered normal. The scale is one of the

most widely used indicators of health risks in the world because it is incredibly easy to calculate.

1

According to the CDC: BMI= (weight in kilograms)/(height in meters) 2 . This means it does use a unit of

measurement: kg/m2. I do not use this for brevity’s sake, however. BMI is an estimate of how much of your body

composition is made up of fat. However, this does not mean that if one has a BMI of 18.5, that one’s body is 18.5%

fat. BMI relies on a standard ratio of muscle to fat, while percent body fat calculations use more accurate methods

to determine body composition. The minimum percent of one’s body that should be composed of fat is often said to

be about 6 or 8% for men and 10 or 13% for women. Very athletic people often have a body fat percentage that falls

within this rage, but have a BMI in the normal or overweight range because of muscle mass. This very fact is the

BMI scale’s largest flaw, and is the source of most criticism of its widespread use.

2

"Global Database of Body Mass Index," World Health Organization, last modified February 2, 2013, accessed

February 1, 2013, http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp.

3

Joslin Diabetes Center. "BMI Calculator for Asians." Asian American Diabetes Initiative. Last modified 2010.

Accessed April 2, 2013. http://aadi.joslin.org/content/bmi-calculator.

89

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

Most people are well aware of the effects of being overweight: cardiovascular disease,

high blood pressure, diabetes; the list goes on. However, people are often less aware of the

effects of being underweight: weakened immune system, cessation of the menstruation in

women, and osteoporosis to name a few.4

The Japanese View of Dieting

Japan has experienced great social and economic changes since the conclusion of World

War II. Japan had been left in ruins after numerous bombings to the mainland—almost every

major city was reduced to the ground. The American occupation rebuilt the government allowing

for the country to rebuild its economy and infrastructure. Japan saw rapid economic growth

during the Korean War, which continued until Japan’s economy burst in 1989.5

Japan’s diet saw typical changes associated with modernization and economic

development in Asia: Japanese total calorie consumption increased; consumption of cereals

decreased; and consumption of protein, vegetables and sugars increased.6 These changes took

place roughly from the 1950s until 1989, when the Japanese diet evened out and the average

calories consumed per day actually began to drop slightly.7 Japanese consumed about 278

calories more per day in 2001 than in 1961, but consumed about 100 calories more on average

per day in 1988 than in 2001.8 The diet changes can be attributed to the growing wealth of the

country—meat and fruits are very expensive in Japan, and as the average person earned more,

they could afford to consume more. They also gained trading partners allowing foods that were

unavailable before to enter the market. Today fast food restaurants are as common in Japan as in

America, and import stores can be found in major train stations and shopping centers.

Today’s Japanese diet consists of rice, noodles, vegetables, chicken, beef, pork, seafood,

bread, and sweets. In the year 2001, the average Japanese citizen consumed an estimated 2746

calories per day.9 Of this, 27% was from oils/fats/sugars, 19% was from meat/eggs/fish/milk and

39% was from cereals.10 This equilibrium has undoubtedly changed as American fast food

businesses find a growing consumer market in Japan, as they are often popular with the youth.

In 2001 about 23.4% of Japanese adults had a BMI of 25 or greater.11 This means that

just over three-fourths of the country fell into the international standard for “normal weight”. An

estimated 3.1% of Japanese people had a BMI equal to or greater than 30 in 2001.12 When the

World Health Organization (WHO) reports obesity rates in countries, they use the percent of the

4

Reese, Megahn. "Underweight: A Heavy Concern." Today's Dietitian, January 2008, 56. Accessed April 2, 2013.

http://www.todaysdietitian.com/newarchives/tdjan2008pg56.shtml.

5

Thomas F. Cargill and Takayuki Sakamoto, Japan: Since 1980 (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press,

2008): 1-3.

6

“Global Database," World Health Organization.

7

"Global Database," World Health Organization.

8

"Global Database," World Health Organization.

9

"Global Database," World Health Organization.

10

"Global Database," World Health Organization.

11

"Global Database," World Health Organization.

12

"Global Database," World Health Organization.

90

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

population with a BMI equal to or greater than 30, thus Japan is reported to have an obesity rate

of 3.1%. However, Japan uses a revised BMI scale that is backed by the WHO, and considers

23.4% of its population to be obese.

American Views on Dieting

The United States has also seen dramatic changes since the conclusion of World War II.

America had been struggling to recover from the Great Depression, and World War II lit the fires

in the war machine. The United States came out of the war thriving economically. America’s

economic growth anchored it as the biggest economy in the world, though there was fear that

Japan would over take it in the 1980s. With the Women’s Rights movement in the 1970s, more

mothers continued to work after childbirth. The social structure within America changed

greatly—increased amounts of two income families and single mothers changed the way meals

were presented in the home, allowing the fast food and instant food industries to take hold.

The economic success of the United States can be seen in the changes to the American

diet. Americans in 1961 ate nearly 900 calories less than Americans in 2001.13 Unlike the

Japanese, who mostly shifted where their calories came from, Americans ate more of everything.

The biggest changes over the years came from increased consumption of cereals, sugars and

fruits. Americans consumed 429 more calories from sugars, fat and oil in 2001 than in 1961.14

The American diet consists largely of beef, various poultry, pork, seafood, bread, rice,

noodles, vegetables and sweets. In 2001, the average American consumed an estimated 3766

calories per day.15 Of this, 39% was from oils/fats/sugars, 24% was from meat/eggs/fish/milk

and 23% was from cereals.16 Americans consumed about 600 calories more in 2001 than in

1980.17 If this trend is stretched to the present day, it is likely that Americans in 2013 consume

around 3900 calories a day. The distribution of BMI is almost the opposite of Japan's.

Approximately 66.9% of Americans in 2006 had a BMI equal to or greater than 25.18 Of that,

approximately half had a BMI equal to or greater than 30.19 This means that about one third of

the country falls into the category of "Obese". On the other end of the spectrum, approximately

2.4% of the population was underweight in 2002.

The Culture of Dieting

「瘦せたい。」 Yasetai. “I want to lose weight,” is one of the most common phrases I

hear. Be it the girls around me in America, the girls around me when I was in Japan, or even

from my own lips, I hear that phrase more often than I should in an ideal world. Overall, the

percent of people with a BMI over 25 in America is dramatically higher than Japan—23.4% of

people in Japan in 2001 compared to 66.9% in America in 2006. This can be attributed to a

13

"Global Database," World Health Organization

"Global Database," World Health Organization

15

"Global Database," World Health Organization.

16

"Global Database," World Health Organization.

17

"Global Database" World Health Organization.

18

"Global Database," World Health Organization.

19

"Global Database," World Health Organization.

14

91

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

number of differences between the two countries. First, the average Japanese person consumes

about a thousand less calories than the average American. The portion of our diets that come

from cereals and oils/sugars/fats are opposite, with 39% of American’s calories coming from

oils/sugars/fats and 39% of Japan’s calories coming from cereals.

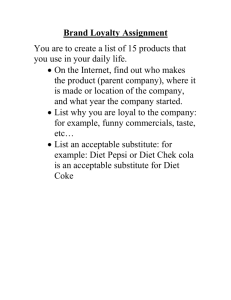

Distribution of the Calories Consumed by

Americans and Japanse in 2001

Average Calories/Day

4000

3500

3000

2500

109

176

1,462

71

175

744

2000

1500

912

1000

246

500

862

519

159

1,073

0

USA

Roots and Tubers

Other

Oils, Sugars, Fats

Meat, Fish, Milk, Eggs

Fruit, Vegetables, Nuts

Cereal

Japan

Country

Figure 1 Source: “Global Database”, World Health Organization.

The Japanese lifestyle is also considerably more active than the American. Japan is a

country where most people walk, ride a bike, take a bus, or ride a train to their destination.20

Train stations often do not have escalators or ramps, forcing commuters to at times climb or

descend as many as three flights of stairs just to exit a station or reach their platform. In the city,

stores are often nestled in out of the way places, up several flights of stairs and without elevators.

Homes are still often in a more Japanese style, and require individuals to sit and sleep on the

floor rather than raised chairs and beds found in Western style homes. Japan is not a good

country to visit if one is walking-impaired, but Japan’s lack of accommodations and environment

that encourages physical activity likely decreases the number of impaired individuals that suffer

because of diseases related to obesity and physical inactivity. Both sets of my host parents are in

much better physical condition than my parents despite being around the same age. It is common

to see middle aged and elderly riding bicycles around the streets.

This is a sharp contrast to the majority of America, where it is difficult to go anywhere

outside the city without the aide of a car, which drastically reduces the number of calories

Americans burn in a day. 55% of Americans wish to walk more; however, the majority of

Americans have reported that the set up of their neighborhoods actually discourage biking and

20

Sometimes even combining methods! When I studied in Japan, I had to walk ten minutes to the nearest train

station, ride 40 minutes into the city, walk to another station, ride another train for 10 minutes, then walk ten

minutes from the station to my school. Another girl in the program alternated between walking ten minutes to a bus

stop to ride the city bus and biking to school.

92

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

walking.21 Outside of a city setting, American neighborhoods are often large housing districts

that are far from stores of any kind. When stores are close, there are usually few to no sidewalks

and sporadically placed major roads that prevent safe travel. Because most neighborhoods are

not designed for pedestrian traffic, bike lanes are rare and cross walks at major intersections are

even rarer. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that only about a fifth of Americans get even

30 minutes of exercise a day.22

Only 5% of college-aged women in Japan in 2012 claimed to have never dieted in their

life. Japanese girls and American girls are exposed to the idea that they must diet to lose weight

until they reach an idealized weight or to maintain a desired weight from a young age. While the

majority of media figures who diet are women, men are now being increasingly targeted as well.

In America, it is difficult to turn on the TV and not see commercials for proportioned meal plans

such as Jenny Craig or Nutrisystem For Men.24 It is about as equally difficult to turn on the TV

in Japan and not see a segment on the news or a variety show about how using a thigh roller will

make your thighs thinner, and stretching like a cat for a month will make you lose several

centimeters off your waistline. Both markets are saturated with tips that actually have no real

impact or do not fix the problem in the long run.

23

The major problem is that few people are aware of what a healthy weight is, what it looks

like, and how such a weight is obtained and maintained. People have taken hold of the second

definition of diet and hold it as an escape. “I want to look like Goo Hara of the popular Korean

girl band KARA; I will diet until I have a 20 inch waist like her,” a woman might say in either

Japan or America. This statement exemplifies everything that is the diet culture in both countries.

“I will diet until I’m a healthy weight.” “I will diet so my blood pressure goes down.” “I will

diet so I can fit into my 3 sizes too small designer wedding dress.” We, as humans, give

ourselves a goal to reach, but the moment we attain this goal, we are no longer on a diet. Once

the diet ends, we return to sitting on the couch and watching the four-hour marathons of NCIS on

the USA Network instead of running on the treadmill and doing armcurls at the gym. We

celebrate by eating our favorite foods: all the sweets and carbs that we’d been denied. Within a

few weeks to months, suddenly we have regained the weight we had lost, our blood pressure is

back up, and the wedding dress no longer fits. This is not the lifestyle of a person who looses

weight and keeps it off.

J. S. Puterbaugh, "The Emperor’s Tailors: The Failure of the Medical Weight Loss Paradigm and its Causal Role

in the Obesity of America," Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism 11, no. 6 (June 2009): 564, accessed March 7, 2013,

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=39143407&site=ehost-live.

21

Puterbaugh, "The Emperor’s Tailors".

21

Puterbaugh, "The Emperor’s Tailor," 563.

See Appendix A

24 Nutrisystem for Men was created as a ploy to attract male customers because in America, dieting is associated

with femininity that male customers actually shy away from it. Nutrisystem’s meal options are slightly different to

reflect a more “masculine” menu. Other companies have also made similar moves in order to increase their

consumer base, with Dr. Pepper as the most notable recent example—they created a diet Dr. Pepper that still had

calories in it because in research men had responded that zero-calorie drinks were too feminine.

22

23

93

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

Figure 2: Goo Hara from the Korean girl idol group KARA during promotions in Japan. Her BMI at the time was

about 14.9 and she had a 20-inch waist. Photograph, 2011, http://www.soompi.com/2012/01/13/goo-hara-shares-

more-photos-from-surprise-birthday-party.

The 1992 National Institutes of Health Conference on Voluntary Methods for Weight

Loss concluded that nearly 30% of weight lost during a diet is regained within a year of ending

the diet.25 Though doctors have officially stated this, any veteran dieter in America can attest to

this without needing a doctor’s confirmation. While the diet industry in Japan is set up slightly

differently from America’s, Japan is close on America’s heels. Puterbaugh claims that America’s

diet system is the only one in the world that is based on unnecessary, optional exercise and diets

focused solely on the nutritional value of foods, but Japan’s health conscious society is quickly

gravitating towards the American Model.26 Calories are a major concern to most Japanese, and in

the words of my host mother, “Most Japanese prefer low calorie, filling food”.

My questionnaire revealed that in Japan, the average college-aged woman does not skip

meals, but cuts out snacking between meals and limits portions of rice when they are on a diet.27

About 59% of college-aged women in Japan in 2012 reported that they walked or jogged as a

way to help lose weight through exercise.28 In addition to walking or jogging, many women

Puterbaugh, "The Emperor’s Tailors,” 562.

Puterbaugh, "The Emperor’s Tailor".

27

See Appendix A

28

See Appendix A

25

26

94

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

participated in sports or dance as a way of staying fit, with some women participating in multiple

forms of physical activity.29 However, with an average height between 157 and 158 centimeters

(5’2”) and an ideal average weight of 44.8 kilograms (98.8 pounds), the average young woman

in Japan would find it difficult to achieve this thin ideal without adding miscellaneous other

activities and tricks to their diet.30 These tricks and activities are often forgotten about when one

thinks about dieting. Drink diet soda instead of regular; buy the fat-free, sugar-free salad

dressing; use a thigh roller each night before bed. However, these tricks aren’t solely limited to

Japanese dieters, as similar tricks are often advocated in American “health articles”.

Japanese Response to Weight Issues

In Japan, and Asia in general, the ideal weight for a woman hovers around 45 kilograms

for a woman of average height or taller—less for a woman shorter than average. In my survey,

the most reported ideal weight was 45 kilograms; female Korean idols active in Japan31 weigh

less than 50 kilograms (110.2 pounds), and are often 45 kilograms or less; the 20 most popular

members of Japan’s most popular female music idol group, AKB4832, have an average waist

measurement of 56.9 centimeters (22 and 2/5 inches).33 The media standard is set at such small

numbers34 that young women that weigh 50 kilograms or above feel an intense pressure to meet

these beauty ideals for both self-fulfillment and cultural-fulfillment.

As a culture that is highly collective, there are strong forces that push and pull Japanese

women to fit into roles and ideals that she may not necessarily chose if the decision was

completely left up to her. As a result, Japan has seen a slow rise in eating disorders over the last

several decades. In 1988 an estimated 2.9% of college women met the criteria for Bulimia.35 In

1996, an estimated 6.3 to 9.7 people per 100,000 suffered from Anorexia Nervosa in Japan.36

The fact that eating disorders are present in Japan at all should signal to the West that big

changes are occurring in the country, as Eating Disorders are considered a primarily Western

29

See Appendix A

See Appendix A

31 Korean Idols have become increasingly influential media figures in Japan in recent years with the Hallyu Wave.

The Hallyu Wave is a phenomenon hitting Asia (and the West, to a lesser extent) similar to the British Invasion in

America with the Beatles and TV shows such as Doctor Who. Korean Music has seen growing popularity in foreign

markets, and many Korean musicians have entered the Japanese language music market in an effort to become even

more successful. KARA and Girls’ Generation (Shoujo Jidai, in Japanese; SoNu ShiDae or SNSD in Korean) are

two of the most successful Korean girl groups currently promoting in Japan.

32 AKB48 is 63 member girl group. The girls with featured roles in music videos and new singles are determined by

voting through CD purchases. The production company that operates AKB48 releases a member ranking each year.

33

See Appendixes A, B, and C respectively

34 People like to complain about Hollywood actors and American musicians being unhealthily or unrealistically

thin, but many of America’s most popular female stars would look fat standing next an Asian Star. I often catch

myself looking at a star with a BMI of 17 standing next to a star with a BMI of less than 16 thinking that the one

with a BMI of 17 looks fat! Yet, if I’m looking at just stars with BMIs around 16 or less, I often call them scarily

thin.

35

Kathleen M. Pike and Amy Borovoy, "The Rise of Eating Disorders in Japan: Issues of Culture and Limitations of

the Model of “Westernization”.," Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 28, no. 4 (2004): 497, accessed January 20,

2013, doi:10.1007/s11013-004-1066-6.

36

T. Kuboki et al., "Epidemiological Data on Anorexia Nervosa in Japan," Psychiatry Research 62, no. 1 (April 16,

1996), accessed April 19, 2012, doi:10.1016/0165-1781(96)02988-5.

30

95

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

problem.

There has actually been an interesting phenomenon occurring in Japan in the last 30 years

in regards to BMI: the population with a BMI of 25 or greater steadily increased between 1976

and 1995, but the average BMI of women between the ages of 20 and 39 fell.37 According to

Shimazu’s study of BMI in Japan over a twenty-year period, the average woman between 20 and

29 in 1976 had a BMI of 21.02, while the average women in the same age group in the early

1990s had a BMI of 20.43. In the same age group, an average man went from 21.49 in 1976 to

22.17 in the early 1990s. The change in BMI is approximately the same in both age groups, but

in opposite directions. In 1976, 9.14% of men and 7.8% of women between the ages of 20 and 29

had a BMI over 25. By the early 1990s 17.02% of men and 6.16% of women between the ages of

20 and 29 had a BMI over 25. In 2001, 10% of women between the ages of 20 and 29, and 16%

of women between the ages of 30 and 39 had a BMI below 18.5.38 These low rates of obesity are

only present in the youth, however. After the age of 40, the percent of the population with a BMI

equal to or greater than 25 spikes to over 20% in each age group. This brought the percent of the

Japanese population with a BMI of 25 or larger to 23.4% in 2001.39

1995 actually saw a lower number of obese young Japanese women than 1976, despite

the overall obesity rate in the country rising during the same period. While obesity in Japan

continues to climb, young women still have an over whelming desire to be thin—to be

underweight. The average height of a woman in Japan is between 157 and 158 centimeters

(approximately 5’2”) and the average college-aged woman’s average personal ideal weight was

44.8 kilograms (approximately 98.8 pounds).40 This means that the average college-aged woman

desires a BMI of 18.14. When asked what celebrities have their ideal body type, college-aged

women responded with actresses or models or idols that were very thin, with small waists, and

thin arms and legs.41

37

T. Shimazu et al., "Increase in Body Mass Index Category since Age 20 Years and All-Cause Mortality: A

Prospective Cohort Study (The Ohsaki Study).," International Journal of Obesity 33, no. 4 (April 2009), accessed

February 3, 2013, http://ehis.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=6&sid=210ba477-6448-4732-838e48047852f2c3%40sessionmgr113&hid=109&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=a9h&AN=375804

53.

38

Pike and Borovoy, "The Rise of Eating," 497.

39

"Global Database," World Health Organization

40

See Appendix A.

41

See Appendix A

96

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

Figures 3 & 4: Model/Actress Kiritane Mirei in a swimsuit and modeling for a summer issue of the magazine Non-No in 2012. 4

of 39 surveyed women listed her figure as their ideal. Figure 3 Source: http://geekskiller.tumblr.com/post/45263549214; Figure 4

Source: http://allthingsiheart.tumblr.com/post/25328419211.

28.2% of college-aged Japanese women considered themselves to always be on a diet.42

12.8% said they have dieted more than 11 times, and 41% said they dieted between one and three

times. Only 2 of 39 surveyed said that they had never dieted. These numbers are startling, but

similar trends have been confirmed in other studies: in 2001/2002, at least half of college aged

females with a BMI between 18.5 and 23 in Japan dieted for extended periods of time.43

While many women in my survey idolized the bodies of media figures, the media is not

the only place where the pressure to be thin exists. In any culture, clothing dictates the physical

norm: shirts are designed to fit the “average” or idealized average physical proportions, and are

available in a range of sizes that is considered normal to that population. Japan is a country of

highly varied fashion styles meant to fit a limited range of sizes. I experienced this first hand

while clothes shopping in Japan. One-size-fits-all44 dresses, shirts, skirts, and pants are not

uncommon in more fashionable clothing chains, though many retailers offer up to three sizes.

These clothes can range anywhere from a maximum waist of 72 centimeters (28 inches) with a

maximum bust and hip of 87 centimeters (34 inches), to a maximum bust and waist of over 130

centimeters (51 inches). The key to note, however, is that the tags inside larger clothing will

sometimes list the intended size of the customer rather than the clothing’s actual dimensions.

42

See Appendix A.

Pike and Borovoy, "The Rise of Eating," 498.

44 Most often referred to as Free-size or F-size and sometimes as M-size

43

97

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

This will often lead to shirts that claim to fit a maximum bust of 87 centimeters but can fit a bust

up to 120 centimeters (47 inches). These large sizes are almost exclusively available for dresses

and shirts. It is difficult to find pants that will fit a person with a waist above 77 centimeters (30

inches).

These clothing sizes present a box for Japanese women to fit into. While it is possible for

women of larger sizes to find clothing, the sizes found in stores often reflect the measurements of

healthy individuals, and the Japanese government even encourages that Japanese citizens above

the age of 40 stay as close to these measurements as possible as they age.45 In 2008, the Japanese

government passed a law aimed at fighting obesity by requiring all men with a waist

circumference larger than 85 centimeters (33.5 inches) and women with a waist circumference

larger than 90 centimeters (35.4 inches) to attend weight loss education classes.46 This law is

supposed to be enforced through yearly check-ups, and insurance companies are expected to face

heavy fines if their client’s weights are not decreased overtime.47 The remedial classes are aimed

at teaching those who have excessively large waistlines to eat and exercise properly in order to

decrease their weight and risk for metabolic disease.48 Whether this approach will work is still

being questioned, but this policy shows how seriously the Japanese government is taking the

situation.

Despite the competitive snack market and growing fast food industries, Japan tends to

have more healthy foods than America. The typical Japanese housewife goes grocery shopping

daily, and buys food in portions that will last only one to two days. Fresh foods are

overwhelmingly preferred. Food is rarely kept around the house long after it is bought or opened.

Ingredient lists tend to be shorter, and foods tend to have fewer preservatives. Condiments aside,

most packaged foods come in single servings or fewer than 3 servings.

Portion sizing in Japan is generally much smaller than in the West. When one goes to

StarBucks in Japan, there is an extra size to choose from: short. When one goes to

McDonald’s—or any other fast food burger place—and orders a S sized meal (a regular size in

American terms), one receives French fries and drink portions that we expect in a child’s meal in

America. Noodle stores will sell hefty portions, but are rarely gut popping without side dishes.

The majority of restaurants will serve portions that are similar, if only slightly larger, than

portions served in the home. Meals are often made up of several small dishes, which usually

leads families to order several dishes to share when they eat at restaurants.

However, Japan’s food scene is changing. More and more restaurants are taking

advantage of a genius marketing ploy: digital menu pads that allow the customer to order food at

any point during the meal. These menu pads can be found in karaoke boxes, izakayas49, merry45

Christin Lawler, "An International Perspective on Battling the Bulge: Japan's Anti-Obesity Legislation and its

Potential Impact on Waistlines Around the World," San Diego International Law Journal 11, no. 1 (June 2009):

293, accessed March 12, 2013,

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=47121477&site=ehost-live.

46

Christin Lawler, "An International Perspective on Battling the Bulge,” 293.

47

Christin Lawler, "An International Perspective on Battling the Bulge,” 293.

48

Christin Lawler, "An International Perspective on Battling the Bulge,” 293.

49 An izakaya is a variety of bar in Japan that serves a wide selection of both food and drinks. While they are centers

for drinking, their menus are quite expansive, and it can be argued that they are often just as much a restaurant as a

bar.

98

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

go-round sushi houses, barbeque restaurants and more. If the environment encourages customers

to stick around, chances are that the table will have a digital menu. These menus, for the simple

fact that they do not leave the table and do not require interacting with a waiter, encourage

customers to order more through the meal. This results in impulse purchases and people eating

more than they initially desired.

All-you-can-eat buffets are also quite common in Japan—as common as in America.

Referred to as Viking, these restaurants often play off a theme that attracts customers, such as

Ninja House and Sweets Paradise in Kyoto. While the rules at these restaurants are different

from American buffets, Japanese buffets still allow for plenty of gorging.

However, the changing restaurant scene does not change Japan’s focus on being healthy

and idolizing thin media figures. Women’s fashion magazines will often take part in instructing

women how to shave off excess fat, and depending on the target audience, will also teach women

how to cook healthy and delicious meals. Magazines aimed at Japanese sub-cultures are also

notorious for extremely thin models, extreme photoshoping, plastic surgery ads, and diet pill

commercials. Among the most offending magazines are those aimed at the Gyaru subculture,

specifically the hostess aimed Koakuma AGEHA magazine. A typical issue of AGEHA will

contain around ten pages dedicated to plastic surgery, diet pills and supplements. AGEHA’s diet

pill advertisements are often eye catching because they feature before and after pictures of

women along side how much weight they reportedly lost and how much their body

measurements changed. The models’ starting weights are usually between 50 and 60 kilograms

(110 and 132 pounds), but usually advertise a final weight of 40 kilograms (88 pounds) or below.

While diet pills seem like they are limited to only subcultures, 40% of college-aged women had

reported using diet pills and drinks, according to one study in 2001.50 This shows that their

influence in the dieting industry is much greater than one may first realize.

50

Pike and Borovoy, "The Rise of Eating," 498.

99

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

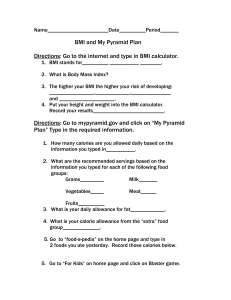

Figure 5: Diet Ad. “Cla-Alpha.” Advertisement. Koakuma AGEHA, November 10, 2012, 116.

This cultural emphasis on thinness, combined with a cultural emphasis on health, is the

most likely origin of today’s young women dieting as much as they do. Yet the weight goals of

most young women are increasingly unhealthy, and many of them seem to not care or not realize

this. At the same time, Japan continues to see increased waistlines in men of all ages and women

over the age of 40. Despite the efforts, despite all the emphasis on avoiding metabolic disorders

and maintaining healthy weights, Japan’s population is going in two completely different

unhealthy directions with its weight.

American Responses to Weight Issues

The range of weights in America is about as vast as the origins of its people. Because

there are such dramatic differences between demographics throughout the country, it would be

hard to come up with just one number that could represent the ideal weight of American women.

A specific number is difficult to pin down for an American ideal weight. However, most collegeage women I know seem to want to have weights between 100 and 140 pounds, and usually want

to be smaller than they currently are.

Clothing in America comes in a wide range of sizes to match the large amount of

diversity within the country; just about anyone with a waist circumference above 26 inches can

find clothing that fits. Women’s sizing is complex—juniors sizing is labeled in odd numbers

(00, 0, 1, 3, 5) and women’s sizing is measured in even numbers (00, 0, 2, 4, 6) and roughly

correspond with each other. Sizing in these sections can also be labeled as Extra Small (XS),

Small (S), Medium (M), Large (L), and Extra Large (XL). Women’s plus size is measured with a

100

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

number and an X (1X, 2X, 3X) or with an even number larger than 14 along side the letter W

(18W, 20W, 22W). Vanity sizing in the West has separated these arbitrary labels from any real

measurement that they once may have represented.51 Clothing manufactures have been slowly

increasing the pattern size of clothing over the decades to play to vanity sizing. When my

grandmother was 20 years old in 1949, she weighed about 120 pounds and wore a size 12. In

2012 at 20 years old, I weighed over 150 pounds and wore a size 10.52 This drastic change in

clothing sizes has taken part in fueling the debates surrounding obesity and eating disorders.

In an issue of PLUS Model Magazine, a plus sized model posed with a normal sized

model. The plus sized model was a size 12 and the normal sized model was a size 0. Amongst

the spread were facts: models used to be only 8% smaller than the average woman, but are 23%

smaller today; the median size of American women is a size 14 but the average store caters to

those sized 14 or smaller; plus sized models are usually between a size 6 and 12.53 However,

when one takes a look at the way sizing has changed over time, half of these arguments fall flat.

Twenty years ago, the average woman weighed less, and much of America’s obesity problem

arose in the last thirty years.54 The obesity rate (% population with a BMI equal to or greater than

30) rose from 14.7% in 1980 to 33.9% in 2006.55 Vanity sizing has probably helped to contribute

to the problem in the United States.

51

Vanity sizing is a term in the fashion industry that refers to labeling a size with a different number than the actual

measurements state in order to make a person feel like they are closer to whatever the culturally acceptable beauty

ideal is. One of the most commonly realized example of this actually occurs in the bra industry. Supposedly, the

numbers and letters are as such because at one time it was more culturally desirable for women to have smaller

breasts, thus companies added inches to a woman’s underbust measurement used to determine the band size, thus

making the cup appear smaller (the cups in a 36B and a 34C bra are the same size; but the 36B will fit a woman with

an underbust measurement of 34 inches). This is still used by many companies today. In terms of clothing, men’s

sizes are measured in inches: a size 42 is meant for a man with a 42-inch waist/hip. This is not true for women; a

woman that wears a size 5 does not have a waist/hip measurement of five inches. Every country has its own separate

system of measurements for clothing and few are untouched by vanity sizing.

52

My grandmother is also a good three inches taller than me to boot, this makes the disparity in the sizes even

greater.

53

PLUS Model Magazine, January 2012, accessed March 17, 2013, http://www.plus-model-mag.com/plus-modelmagazine/magazine-archives/.

54

"Global Database," World Health Organization.

55

"Global Database," World Health Organization.

101

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

Figure 6: Two pages from PLUS Model Magazine, depicting a size 0 model next to a size 12 model; Photography,

January 2012, plusmodelmag.com

As sizes slowly grew larger, Americans subconsciously began to accept larger and larger

sizes as normal and healthy. However, American’s eventually found themselves with a large

population of people that still did not fit into the constraints of sizes S through L; Plus sizes were

created in an effort to fit the exceedingly large (for XL and 1X are often the very similar in size,

and technically mean the same thing), and sizes 0 and 00 were created to fit those who were

exceedingly small. Those who fall into the outer sizes often receive criticism. “Eat a burger” is

one of America’s favorite lines to say to a person who wears a size 00, while “Go on a diet” is

one of the favorites to say to a person who wears a size 4X. Yet through the years, what falls into

the range of “normal” has slowly grown in size. This has resulted in criticism flying everywhere.

Realizing that a size 12 today is not the same as a size 12 half a century ago, complaining that

the average clothing retailer does not cater to the average woman only helps facilitate the

American population to accept weights that put women at a higher risk for various health

problems. But in opposition to this, the media and cultural beauty ideals are heavily invested in

portraying beauty as underweight, thus culturally shoehorning American women into feeling a

constant pressure to diet and be thin in order to feel good about themselves. Women in America

are thus forced into a situation that set us up for a yo-yo diet lifestyle.

This sets Americans up for a variety of eating disorders. An estimated 0.5% of Americans

suffered from Anorexia Nervosa in 2006, while an estimated 2 to 3% of Americans suffered

102

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

from Bulimia Nervosa.56 Some estimates of Eating Disorder rates estimate that numbers are even

larger, potentially as high as 5% of the population. Solid statistics for eating disorders are

difficult to find because nearly every study comes up with a different rate. However, the

occurrence of eating disorders in America is due in part from the pressures placed on women to

fit into certain societal roles, and the pressure to be thin only contributes to the problem. The rate

of eating disorders has led activists such as those at PLUS Model Magazine to fight back against

the skinny advertising norms.

Weight is a beloved topic in American culture. For each activist talking about the fashion

industry’s preference for small sizes fueling eating disorders, there is a politician equally set on

making the population fit into those small clothes through legislation. In recent years, the most

prominent political figure in the fight against obesity is Michelle Obama (1964-present). Since

becoming the First Lady in 2008, Michelle Obama has been pushing for reforms in school food

policies. Two of her major initiatives are to make nutritional information on food packaging

easier to read and to get Athletes to help endorse healthy lifestyles to school-aged children.57 She

has also pushed for laws that will increase nutritional information taught in school and regulate

food sold in schools through government standards.58 She has called for junk food

manufacturers to clean up their recipes and make their snacks healthier, as well as pushed for

schools and childcare facilities to serve healthier foods.59 Michelle Obama has taken the issue of

obesity and the way we raise our children in an unhealthy manner and forced America to

consider alternatives.

Michelle Obama’s actions are filled with good intentions, but the enacted policies have

created other problems, as well as ignored other issues with youth diets. Many parents have

gotten in arguments with their children’s school as a result of the new food regulations. These

regulations often ignore individual preferences in children, as well as call into question a parent’s

ability to properly feed his or her child. This has opened a debate as to whether parents or the

government know the proper way to provide nutrition to children. Many doctors, dietitians and

other health experts expressly disagree with the government’s food pyramid, and a plethora of

alternate pyramids have been created to reflect this. Parents who disagree with the government’s

pyramid are forced to abide by it as long as their child is in school. The government’s food

pyramid is also highly susceptible to lobbying. Despite all the studies on the chemical

breakdown of food in the body, the food pyramid advocates more grains and fewer vegetables

than many dietitians would consider optimal for weight loss. Farming industries and food

manufacturers actively lobby to protect their place in America’s food industry.

Schools also often provide the students with meal and drink options that many dietitians

and doctors would flinch at. While many schools ban the sale of soda on campus, vending

machines often contain juices and sports drinks instead—both of which are just as sugar laden as

soda. While school menus have been cleaned up through Michelle Obama’s initiatives, the

56

"Eating Disorder Statistics," South Carolina Department of Mental Health, last modified 2006, accessed March

19, 2013, http://www.state.sc.us/dmh/anorexia/statistics.htm.

57

Michael Tennant, "Michelle Obama's Federal Fat Farm," The New American, September 13, 2010, accessed

March 19, 2013, Academic Search Complete (53455064).

58

Michael Tennant, "Michelle Obama's Federal Fat Farm".

59

Bridget Huber, "Michelle's Moves," The Nation, October 29, 2012, accessed March 19, 2013, Academic Search

Complete (82713884).

103

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

options are still not always the healthiest—especially school breakfast programs, where

carbohydrate and sugar heavy breakfasts are often the most popular or only choices.

Schools are not the only places that are seeing political action about dieting; New York

has been in the news because of a short-lived ban on the sale of sodas in quantities larger than 16

ounces.60 Taxing sodas is also a popular alternative that many politicians have debated over the

years.61 Taxing is one of the most popular monetary policies that a government can use in order

to control the consumption of a good. This is a serious consideration for governments because

the tax revenue can be used for other programs aimed at decreasing obesity rate.

Recommendations

Dieting culture has led to a spiral of weight loss and weight gain. Sometimes diets are

started with the intent of making a lifestyle change that never comes to fruition, other times it is

because we lack foresight and knowledge about how weight is actually gained and lost. Both can

be fixed through better health education, though not necessarily through nutritional education.

For all the controversy around what Michelle Obama is pushing in the political realm, she is on

to something. The world needs more education about weight issues, but what needs to be taught

needs to go far beyond just teaching children the difference between healthy and unhealthy

foods. Both Japan and America need programs that are aimed at teaching children and teenagers

the biology of weight gain and weight loss, as well as the poor health conditions that can result

from being extremely over and underweight. We should not have to wait until college to learn

about the detailed biology of the human body.62

Education about weight issues should start from a young age. Students should learn what

a healthy weight looks like for a variety of different levels of physical fitness. The chemical

breakdown of food, the processing of food in the body, and the meaning behind the various

measures of health should all be explained from a fairly young age. School Physical Education

PE classes, in all levels of schooling, should also be revamped to help students find exercise

activities that they find enjoyable and want to carry on for life. Students, especially in America,

should be encouraged to participate in extracurricular sports, exercise classes and exercise-based

clubs.

Japan specifically needs to look at what is happening to its young women. The social and

cultural position of women has drastically changed over the last several decades. This has no

doubt affected how young women perceive themselves and how they should look, resulting in

dieting and eating behaviors that could potentially hurt the population as a whole. Underweight

60

Tom Watkins, "NYC Appeals Ruling on Big-Soda Ban," This Just In, last modified March 29, 2013,

http://news.blogs.cnn.com/2013/03/29/nyc-appeals-ruling-on-big-soda-ban/.

61

"The Soda Tax: Potential Weapon in America's War against Obesity," Environmental Nutrition, June 2010,

accessed March 7, 2013, http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=51009508&site=ehostlive.

62

Despite all my random knowledge in regards to weight and weight loss, I did not learn crucial information about

the life of fat cells until a college level Social Psychology class went over the subject while explaining eating

disorders. The fact that fat cells divide and never go away once there (they just get smaller) should be something

taught in health classes as soon as students have a basic understanding of cell life. This little fact only helps show

that in order to keep weight off in the long run, one cannot simply diet but must make lifestyle changes.

104

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

women have a high risk of becoming infertile due to not having enough fat to support pregnancy.

As a country that is facing a shrinking population and wants to increase its fertility rate, Japan’s

government should look into putting more emphasis on women that are in a more healthy weight

range.

America specifically needs to work on infrastructure in non-urban areas. Pedestrian

traffic should be accommodated through increased sidewalks and crosswalks, better suburban

planning, and increased public transit. This is incredibly expensive to change, but the benefits to

the health of our population would be great. America has moved away from walking and biking,

but at least making the incentive to do those two things more often will help decrease America’s

obesity rate.

America should also consider passing taxes on foods that are linked to obesity issues

rather than pursuing bans. Taxes will meet less resistance than bans, and will make the incentive

to buy cheaper junks foods over more expensive health foods smaller.

Both countries need to shift away from dieting as a solution to the problem altogether.

Emphasis should be placed on living a healthy lifestyle rather than placing temporary limits on

food. Both Americans and Japanese need to shy away from diets and focus on their diet and how

it can be improved permanently to make a difference. Japan has attempted this with its programs

aimed at those over the age of forty, but it is difficult to force people to lose weight that way.

The best thing that each country can do in this regard is to educate their population on the basics

and allow people to make the decision on their own. Educated parents can educate children.

Dieting culture has played into the idea that weight gain can easily be reversed and that it is an

individuals sole responsibility to lose weight. As humans, we need to move away from putting

individuals to blame for their weight, and work towards changing our life styles as a society.

105

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

Appendix A: Diet Survey in Japan

Introduction and Methods

In the fall of 2012, while I was in Japan, I conducted a survey of college-aged women in

Japan on their dieting habits. The original ideas for each question were first written in

English. I then refined and constructed each question in Japanese with the aide of Japanese

language professors and teaching assistants. While I tried to provide a variety of options for

each question, I decided to include a blank spot to allow participants to add additional

information. To collect the data, I asked college-aged women if they were willing to fill out

the survey. The only restrictions on the survey were that participants must be female, and

must be between 18 and 23. In total, there were 39 participants. Included in the survey,

the number of respondents that chose each option will be listed.

Survey and Results

1)理想の体重は何キロですか? What is your real height and ideal body weight?

ID#

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Height

Weight

(m)

(kg)

AVG

1.57

52.5 MEDIAN

1.68

50 MODE

1.62

50

1.6

50

1.6

50

1.535

50

1.75

49

1.63

48

1.6

48

1.57

48

1.6

46

1.58

46

1.63

45

1.61

45

1.58

45

1.58

45

1.58

45

1.57

45

1.56

45

1.55

45

1.58

43

1.51

43

1.57

43

1.53

40

1.53

40

1.53

40

1.53

39

1.45

30

Height Ideal Weight

(meters)

(kilograms)

Ideal BMI

1.573243243 44.84615385 18.14120922

1.57

45 18.06616734

1.58

45 18.02595738

106

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

1.56

1.545

1.48

1.58

1.5

1.61

1.52

1.53

1.66

45

46

43

42.5

43

43

38

50

39

44

50

2)ダイエットしたことがありますか?何回ですか? Have you ever dieted? How many times?

(37)はい Yes

(16)1〜3回 1-3 times

(3)4〜6回 4-6 times

(1)7〜10回 7-10 times

(5)11回以上 more than 11 times

(11)いつもダイエットしています。I’m always dieting

(2)いいえ No

3)いつダイエットしますか?(季節と大事なイベント)≪複数回答可≫

When do you diet? (Season, and big events) [Chose all that apply]

(31)夏summer (9)春spring (9)冬winter (3)秋fall

(2)デート前に Before a date (4)旅行前に Before a vacation trip

(1)休み前に Before a break/vacation (8)休み中 During a break/vacation

(3)結婚式前に Before a wedding (3)卒業式前に Before graduation

(3)留学から帰ってから After studying abroad

(6)その他 Other_________________

4)ダイエットするとき、どんなことしますか?≪複数回答可≫

When you diet, what kinds of things do you do? [Chose all that apply]

(18){

}を食べません I don’t eat {

}

(29){朝ごはん・昼ごはん・晩ごはん・間食}をたべません I don’t eat {Breakfast/Lunch

Dinner/In between meals}

(1)ダイエットサプリを飲みます I take diet supplements (diet pills)

(16)その他 Other______________

5)痩せるために運動しますか?どんなことをしますか? Do you exercise for the purpose of

losing weight? What kinds of things do you do?

(34)はい Yes

107

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

(11)スポーツ Sports

(7)ダンス Dance

(23)ジョギング・ウォーキング Jogging/Walking

(0)ウェートリフティング Weightlifting

(8)その他 Other_________

(5)いいえ No

6)有名人で誰が理想の体型ですか? Within Famous People/Celebrities, who has the ideal

body?

Appendix B: Korean Idol Weights and BMIs

Introduction and Methods

Korean Music companies often publish the height and weight of each member in an

idol group when the group debuts. This information can often be found on a group’s official

website, or will be published in some magazines when a group does a photo spread. This

information is some taken down, but fans tend to keep meticulous records and will often

have these measurements in their archives. The data I collected is from one such fan

archive. The weights are subject to change, but are rarely updated, or are real. Height and

weight is often fudged to represent an ideal weight and height. Thus, even if the data is not

correct for each girl at any moment, it presents a cultural ideal. I have taken the weights

and heights of each girl from the following Korean girl groups that are promoting in Japan

and calculated their BMI.

Source:

http://sumandu.wordpress.com/kpop-profiles/

Charts

Girl's

Generation

TaeYeon

Jessica

Sunny

Tiffany

HyoYeon

Yuri

SooYoung

Yoona

SeoHyun

Height

Weight

(m)

(kg)

BMI

1.62

44 16.76573693

1.63

43 16.18427491

1.58

43 17.22480372

1.62

50 19.05197378

1.62

48 18.28989483

1.67

45 16.13539388

1.7

45 15.57093426

1.66

47 17.05617651

1.68

48 17.00680272

Rainbow

Jaekyung

NoEul

SeungAh

Height

Weight

(m)

(kg)

BMI

1.68

45 15.94387755

1.64

44 16.35930993

1.67

45 16.13539388

108

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

YoonHye

Jisook

WooRi

HyunYoung

1.66

1.64

1.65

1.6

47 17.05617651

41 15.24390244

44 16.16161616

41

16.015625

Kara

JiYoung

Nicole

Hara

SeungYoon

Gyuri

Height

Weight

(m)

(kg)

BMI

1.68

48 17.00680272

1.67

45 16.13539388

1.64

40 14.87209994

1.6

43

16.796875

1.6 -

4minute

Jihyun

Gayoon

Jiyoon

Hyuna

Sohyun

Height

Weight

(m)

(kg)

BMI

1.68

50 17.7154195

1.65

49 17.99816345

1.65

48 17.63085399

1.62

48 18.28989483

1.59

49 19.38214469

Appendix C: Three Measurements from Mega Girl Idol Groups in Japan

Introduction and Methods

Japanese music companies will often publish a set of measurements often referred

to as the “three measurements” for idols at or after debut. The three measurements refer to

bust circumference, waist circumference, and hip circumference. Height is also included

with these measurements, but weight is not. Japanese music companies rarely make an

idol’s weight public. Like Korean idol information, the data is published on official sites but

often removed at a later date. Fan run websites keep archives of this info. Below I have

listed the three measurements of the 20 most popular members of AKB48, and 20

members of the group SKE48.

Source: http://stage48.net/wiki/index.php/Main_Page

Charts:

AKB48 top

1 Yuko Oshi

Wata

2 Mayu

3 Kashi Yuki

4 Sashi Rino

Shino

5 Maki

6 Taka Mina

7 Kaji Haru

Height (cm) Bust (cm)

Waist (cm)

Hip (cm) WHR

152

77

55

78

0.705128205

154

163

159

72

76

73

55

54

53

82.5

81

81.5

0.666666667

0.666666667

0.650306748

168

148.5

164

87

73

80

57

53

60

85

78

86

0.670588235

0.679487179

0.697674419

109

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

8 Ita tomo

9 Matsu Juri

Matsu

10 Rena

11 Miya Sae

Kasa

12 Tomo

13 Kita rie

Mine

14 Mana

15 Yoko Yui

16 Ume Aya

17 Taka Aki

Yama

18 Saya

Wata

19 Miyu

20 Aki Saya

Mean

Median

Min

Max

154

160

75

74

55

59

78

83

0.705128205

0.710843373

162

164

75

80

52

59

85

84

0.611764706

0.702380952

153

157

80

78

59

57

82

83

0.719512195

0.686746988

158

158

151.5

164

80

74

78

82.5

60

60

59

56

86

86

82

88

0.697674419

0.697674419

0.719512195

0.636363636

85

83

83

78

88

0.717647059

0.685653682

0.697674419

0.611764706

0.719512195

155 -

-

-

154.5 166

86

61

158.275 77.80555556 56.88888889

158

77.5

57

148.5

72

52

168

87

61

SKE48

Height (cm) Bust (cm) Waist (cm)

Hip (cm) WHR

1 Oya Masa

158

74

59

81

0.728395062

2 Kato Rumi

152

73

59

81

0.728395062

3 Kita Yuri

154

76

61

84

0.726190476

Kito

4 Momo

159

80

61

90

0.677777778

5 Kino Yuki

160

75

58

83

0.698795181

Suga

6 Nana

160

81

61

85.5

0.713450292

7 Suda Aka

160

77

57

75

0.76

8 Degu Aki

162

79

57

86

0.662790698

9 Nishi Yuu

161

75

59

84

0.702380952

Matsu

10 Juri

160

74

59

83

0.710843373

1 Aka Riri

166

78

60

86

0.697674419

2 Igu Shio

174

81

60

88

0.681818182

3 Ishi Anna

153

72

56

81

0.691358025

Kato

4 Tomo

158

78

60

80

0.75

5 Goto Risa

157

73

59

80

0.7375

6 Sato Seira

158

88

59

87

0.67816092

Sato

7 Mieko

148

79

57

80

0.7125

110

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

8 Taka Aka

Hata

9 Sawa

10 Furu Airi

Mean

Median

Min

Max

154.2

75

59

82

0.719512195

153

155

158.11

158

148

174

80

80

77.4

77.5

72

88

57

61

58.95

59

56

61

81

86

83.175

83

75

90

0.703703704

0.709302326

0.709527432

0.71007285

0.662790698

0.76

Bibliography

Cargill, Thomas F., and Takayuki Sakamoto. Japan: Since 1980. New York, NY: Cambridge

University Press, 2008.

Huber, Bridget. "Michelle's Moves." The Nation, October 29, 2012, 11-17. Accessed March 19,

2013. Academic Search Complete (82713884).

Joslin Diabetes Center. "BMI Calculator for Asians." Asian American Diabetes Initiative. Last

modified 2010. Accessed April 2, 2013. http://aadi.joslin.org/content/bmi-calculator.

Kiritani Mirei. Photograph. Accessed March 19, 2013.

http://geekskiller.tumblr.com/post/45263549214.

Kiritani Mirei in Non-No. Photograph. Accessed March 19, 2013.

http://allthingsiheart.tumblr.com/post/25328419211.

Kuboki, T., S. Nomura, M. Ide, and H. Suematsu. "Epidemiological Data on Anorexia Nervosa

in Japan." Psychiatry Research 62, no. 1 (April 16, 1996): 11-16. Accessed April 19,

2012. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(96)02988-5.

Lawler, Christin. "An International Perspective on Battling the Bulge: Japan's Anti-Obesity

Legislation and its Potential Impact on Waistlines Around the World." San Diego

International Law Journal 11, no. 1 (June 2009): 287-317. Accessed March 12, 2013.

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=47121477&site=ehost

-live.

Medical Science. "Cla-Alpha." Advertisement. Koakuma AGEHA, November 10, 2012, 116-17.

Pike, Kathleen M., and Amy Borovoy. "The Rise of Eating Disorders in Japan: Issues of Culture

and Limitations of the Model of “Westernization”." Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 28,

no. 4 (2004): 493-531. Accessed January 13, 2013. doi:10.1007/s11013-004-1066-6.

PLUS Model Magazine, January 2012. Accessed March 17, 2013. http://www.plus-modelmag.com/plus-model-magazine/magazine-archives/.

Puterbaugh, J. S. "The Emperor’s Tailors: The Failure of the Medical Weight Loss Paradigm and

its Causal Role in the Obesity of America." Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism 11, no. 6

(June 2009): 557-70. Accessed March 7, 2013.

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=39143407&site=ehost

-live.

Reese, Megahn. "Underweight: A Heavy Concern." Today's Dietitian, January 2008, 56.

Accessed April 2, 2013.

http://www.todaysdietitian.com/newarchives/tdjan2008pg56.shtml.

Shimazu, T., S. Kuriyama, K. Ohmori-Matsuda, N. Kikuchi, N. Nakaya, and I. Tsuji. "Increase

in Body Mass Index Category since Age 20 Years and All-Cause Mortality: A

Prospective Cohort Study (The Ohsaki Study)." International Journal of Obesity 33, no.

4 (April 2009): 490-96. Accessed February 3, 2013.

111

Virginia Review of Asian Studies

http://ehis.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=6&sid=210ba477-6448-4732-838e48047852f2c3%40sessionmgr113&hid=109&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d

%3d#db=a9h&AN=37580453.

"The Soda Tax: Potential Weapon in America's War against Obesity." Environmental Nutrition,

June 2010, 3. Accessed March 7, 2013.

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=51009508&site=ehost

-live.

South Carolina Department of Mental Health. "Eating Disorder Statistics." South Carolina

Department of Mental Health. Last modified 2006. Accessed March 19, 2013.

http://www.state.sc.us/dmh/anorexia/statistics.htm.

Stage 48. Last modified March 3, 2013. Accessed March 20, 2013.

http://stage48.net/wiki/index.php/Main_Page.

Sumandu, Akmalya, Jomarie, and SunJanho, eds. "K-Pop Profiles." The KPop Guru.

http://sumandu.wordpress.com/kpop-profiles/.

Tennant, Michael. "Michelle Obama's Federal Fat Farm." The New American, September 13,

2010, 15-20. Accessed March 19, 2013. Academic Search Complete (53455064).

Tom Watkins, "NYC Appeals Ruling on Big-Soda Ban," This Just In, last modified March 29,

2013, http://news.blogs.cnn.com/2013/03/29/nyc-appeals-ruling-on-big-soda-ban/.

World Health Organization. "Global Database of Body Mass Index." World Health Organization.

Last modified February 2, 2013. Accessed February 1, 2013.

http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp.

Yoshiike, N., F. Seino, S. Tajima, Y. Arai, M. Kawano, T. Furuhata, and S. Inoue. "Twenty-Year

Changes in the Prevalence of Overweight in Japanese Adults: The National Nutrition

Survey 1976–95." Obesity Reviews 3, no. 3 (August 2002): 183-90. Accessed February 3,

2013. http://ehis.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=3&sid=0903f013-f56d-4e7e-8668ef47c31b3a4f%40sessionmgr13&hid=114&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%

3d#db=a9h&AN=6911547.

112