DRA - CHAPTER 4: DIAGNOSTIC READING ASSESSMENTS

advertisement

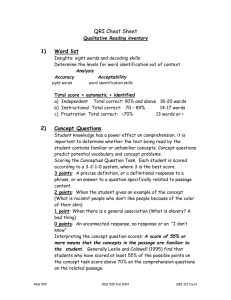

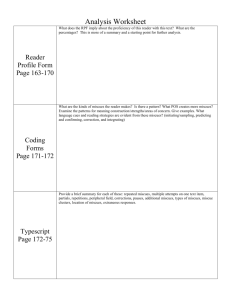

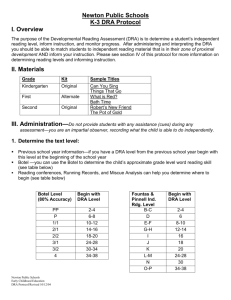

DRA - 1 CHAPTER 4: DIAGNOSTIC READING ASSESSMENTS Sunday, 7.27.2014 –11:26 a.m. A pig doesn’t get any heavier by weighing it. A house doesn’t get any warmer by adding thermostats. As the farmer once said, “The pig don’t get any heavier by weighing it.” Meaning that, in education in general, and special education in particular, there tends to be too much emphasis on assessment and not enough emphasis on teaching. *[Andy note, 7.27.14 -- I’d like to create a DRA with graded word lists and leveled reading passages on a website for use with this chapter.-7.26.2014-] DIAGNOSING THE PROBLEM Here’s the problem: You’ve got a student named Billy who is struggling to learn to read. You look at his IEP and it tells you that Billy can’t read. On his IEP you see bunch of numbers from standardized tests. These numbers show you how much Billy can’t read in comparison to everybody else. Percentages and percentile rankings are used to describe Billy in terms of his distance from average. But then what? Billy still can’t read. You still don’t know why Billy can’t read and you don’t know what specifically you should do about it. Percentile rankings and standardized test scores won’t give you this type of information. Limitations of Standardized Tests There’s nothing inherently wrong with standardized tests. They are one of many types of tools that can be useful in helping struggling readers; however, with any tool, you must recognize the limitations. For reading, most standardized tests are insufficient for (a) diagnosing the possible cause of a reading disability, (b) identifying student strengths as well as specific areas for remediation, and (c) informing your planning and instruction. To do this, you need another type of tool. I recommend some form of a Diagnostic Reading Assessment (DRA). Diagnostic Reading Assessments A common term for Diagnostic Reading Assessments (DRA) is an Informal Reading Inventory (IRI). However, the term, ‘Informal Reading Assessment’ may imply to some that it is haphazard or that it is somehow less valuable than other “formal” types of measures. In the hands of a knowledgeable teacher, a DRA provides valuable data than cannot be obtained on DRA - 2 standardized tests. Thus, I prefer the term, Diagnostic Reading Assessment. With the DRA, the examiner is not simply following a formula and list of sequential steps. Instead, the knowledge and experience of the examiner becomes an integral part of the assessment (cite). Figure 4.1 contains a list of common commercially-prepared DRA’s. The information in this chapter will enable you to use any of these. I will also show you how to design and implement your own DRA’s. Figure 4.1. Common Diagnostic Reading Assessments • Qualitative Reading Inventory, 5th edition, (Leslie and Caldwell) • Reading Inventory for the Classrooms,5th edition, (Flynt and Cooter) • Classroom Reading Inventory, 12th edition, (Silvaroli and Wheelock) • Basic Reading Inventory, 10th edition, (Johns) • Analytical Reading Inventory, 9th edition, (Woods and Moe) • Ekwall/Shanker Reading Inventory, 6th edition, (Shanker and Ekwall) • Informal Reading Inventory, 8th edition, (Roe and Burns) The DRA is used to determine students’ approximate independent and instructional reading levels (see Figure 4.2), as well as their strengths and deficit areas related to word identification, fluency, and/or comprehension. The basic elements include (a) graded word lists, (b) graded reading passages, and (c) comprehension questions or a maze. Each of these is described below. Figure 4.2. Independent, instructional, and frustration levels. • Independent level. At this level students can read unassisted. They are generally able to identify 98% or more of the words. Comprehension scores are 90% or higher. When students read independently for pleasure, you want them to be reading at this level or BELOW. • Instructional level. At this level students can read with some assistance. They are generally able to identify 90-97% of these words. Comprehension scores are between 75% and 89%. This is the level of reading material that should be used for reading instruction. Here you will need to provide some assistance such as a story map, vocabulary help, scaffolded oral reading, or a story preview. • Frustration level. At this level students cannot be successful even with a lot of the teacher’s help. They are able to identify 89% or less of these words. Comprehension scores are less than 75%. Avoid any type of reading at this level. Challenging students with frustration level material will NOT help them progress faster. Reading at this level results only in frustrated students who learn that they can’t learn to read and that they don’t like reading. GRADED WORD LISTS Graded word lists provide a very general estimation of students’ reading grade level. These are used to inform the next part of the DRA. An example of graded word lists can be found in Figure 4.3. As well, graded word lists are included in Appendix A. Figure 4.3. Graded word lists for Primer through Grade 4. DRA - 3 Primer 1. was 2. could 3. children 4. know 5. what 6. saw 7. around 8. mother 9. now 10. old 11. fly 12. very 13. have 14. into 15. yellow 16. tree 17. what 18. about 19. went 20. cake 21. all 22. way 23. hold 24. your 25. over First Grade 1. please 2. flower 3. snowman 4. brown 5. children 6. father 7. drop 8. birthday 9. men 10. kind 11. story 12. cry 13. tell 14. street 15. buy 16. why 17. rabbit 18. ball 19. walk 20. paint 21. behind 22. give 23. her 24. again 25. laugh Second Grade 1. beautiful 2. everyone 3. should 4. write 5. sorry 6. people 7. instead 8. breakfast 9. cupcake 10. eyes 11. love 12. reach 13. people 14. save 15. strong 16. carry 17. first 18. together 19. friend 20. present* 21. write 22. hurt 23. fall 24. until 25. does Third Grade 1. magic 2. beginning 3. thankful 4. crawl 5. museum 6. reason 7. bush 8. planet 9. discover 10. enough 11. precious 12. fright 13. honor 14. several 15. unusual 16. hour 17. escape 18. wiggle 19. soup 20. enemy 21. either 22. remember 23. matter 24. inventor 25. diamond Independent Instructional Frustration 25, 24, 23 22, 21, 20, 19 18 or less Fourth Grade 1. predict 2. knowledge 3. canoe 4. vicious 5. decorate 6. windshield 7. parachute 8. official 9. dignity 10. island 11. dozen 12. exercise 13. bound 14. machine 15. experience 16. motion 17. coward 18. servants 19. legend 20. force 21. nephew 22. barrel 23. weather 24. ghost 25. weight These are the steps for using graded word lists: 1. Record each session with an audio recorder. Start by having students say their name, age, and grade level. This will enable you to identify the correct recording when you go back to analyze it. 2. Start below students’ estimated reading grade level. 3. Ask the student to read the word list out loud. Have a duplicate list in front of you to keep track of the words correctly identified. Put a ‘+’ next to words correctly identified and a ‘0’ next to those words that are not correctly identified. [sample?] 4. After completing the list check the number of errors. Keep moving up until you reach the student’s instructional level. The number of words correctly identified for each level is shown in Figure 4.3. 5. Based on the information from these word lists, select a graded reading passage that is at the student’s independent reading level for the graded reading passage. This is the next part of the DRA. 6. When you have completed the other parts of the DRA, go back and analyze the audio recording of these graded word lists. Start by analyzing the misidentified words. Write down exactly what the student said next to the target word. Then record your observations in regards to how the student identified the word. How did he or she say the word? Did the student recognize the word instantly? Did the student sound out each letter? Did the student recognize DRA - 4 word parts? Did the student quickly guess? Did the student self-correct? Were there patterns of words miscued? Record your observations directly on the word list. Your observations and analysis provide valuable information for your diagnostic assessment. GRADED READING PASSAGES Graded reading passages are texts that have been normed for a particular grade level. This means that the average student at a particular grade level could read the passage independently. For example, RL3 (reading level 3) means that 50% or more of all third grade students could read that passage at the independent level. Sometimes graded readers are broken down further by month. RL 3.2 means reading level, 3rd grade, 2nd month. The commercially prepared DRAs listed in Figure 4.1 have graded reading passages included. However, you can prepare your own DRA by using basal readers that have been normed for a particular level or children’s books. On the back of most children’s books you will see RL followed by a number. This indicates the approximate reading grade level. These are the steps for using the graded reading passages: 1. Just like the words lists, record each session with an audio recorder. Start recording at the beginning of each graded passage. Record each section of the DRA individually because you will often need to listen to individual passages or word lists more than once. Recording each element separately enables you to move quickly back and forth between elements. 2. Give students a copy of a graded passage that is at their independent reading level based on the graded word lists above. Provide the title of the passage and then ask them to read it out loud. Tell them also that they may know some words but not others. Provide help or hints only when absolutely necessary. Give students plenty of space to self-correct words and sentences but use your teacher sense to avoid frustrating them. Remember, the purpose here is to collect data. Frustrating students will affect the quantity and quality of the data you get. 3. Have copy of what students are reading in front of you. As they read, put a line through the miscued words. A miscue is when what the student says does not match what is on the page (see Figure 4.7). Also, make quick notes of some of your initial impressions in the margins as the student is reading. Focus on things such as facial expression, body language, general confidence, and word identification strategies used. Note anything that stands out here. This is all important data that will help you understand each reader. But do not try to write too much here. You will be going back later to listen to the audio recording in order to engage in a more thorough and precise analysis. 4. Most commercially prepared DRAs have five or six comprehension questions followed by a scoring guide (Figure 4.4). After reading the passage orally ask these questions and record students’ responses. Note that the comprehension part of the DRA is optional. If you are creating your own DRA and you want to assess comprehension, use a story re-telling rubric (see Figure 4.8). Figure 4.4. Example of a scoring guided for comprehension questions. COMPREHENSION # correct Level DRA - 5 5½ to 6 4½ to 5 4 or less Independent Instructional Frustration 5. If students are able to identify 98% of the words or more (independent reading level), move up to the next reading level passage. Commercially prepared DRAs will indicate exactly what this numbers is. If you are using your own graded reading passage, count the number of words and figure out percentages before administering the DRA. Stop when students reach their instructional level (90% to 97% of words correctly identified). We can assume that anything above students’ instructional level is their frustration level. For example, if 2nd grade reading passage is at a student’s instructional level, we can assume that 3rd grade reading passages will be at his or her frustration level. There may be differences in word identification and comprehension levels. For example, when reading a passage at the 2nd grade level Pat might correctly identify 98% of the words (independent level), yet score only 75% on comprehension measures (instructional level). This tells us that comprehension may be an area to focus on. Qualitative Data Analysis It usually works best to do the initial qualitative data analysis as soon as you have finished working with the student. In this way, the experience will be fresh in your memory. In the qualitative data analysis you are focusing on observed behaviors related to fluency and word identification as well as students’ general demeanor and your over-all impressions. These are the steps: 1. Before listening to your audio recordings, do a quick analysis. Write directly on the copy of the graded reading passage you used above. Was the student able to read the passage fairly easily and create meaning? Or did the student struggle? What type of reading behaviors did you notice? What was your impression of that student’s attempt to create meaning with print? Describe any interesting or important analyses, descriptions, or observations. 2. Analyze the word identification strategies used while reading. The questions in Figure 4.5 can be used to inform your analysis. Figure 4.5. Listening for word identification strategies 1. What does the student do to identify words? 2. Does the student use context clues? 3. Does the student recognize word parts? 4. Does the student use onsets to identify unknown words? 5. Does the student over-use phonics? 6. Does the student self-correct? 7. Are the miscues schema-related? 8. What types of miscues does the student make? 9. Does the student recognize and use morphemes (prefixes, suffixes, and roots)? 10. Does the student correctly identify the onset or beginnings of miscues words? DRA - 6 3. Analyze students reading fluency. The questions in Figure 4.6 can be used to inform your analysis. Figure 4.6. Listening for reading fluency 1. Is the reading choppy, word-by-word? 2. Is the reading choppy, letter-by-letter? 3. Does the student pause at the ends of sentences? (prosody) 4. Is the inflection appropriate to the sentence or passage? 5. Does the student pause to check for understanding (metacognition)? Miscue Analysis Now you are ready to conduct the miscue analysis portion of the DRA. A reading miscue is anytime there is a difference between what is on the page and what students say. We do not use the word ‘error’ because reading miscues often represent mature reading behavior. Four types of miscues and their meanings are described in Figure 4.7. Figure 4.7. Hierarchy of miscues. Types of Miscues • Meaningful miscue - sentences still retains the original meaning • Schema-related miscue - similar concept, sentence meaning not retained • Significant miscue - sentence meaning not retained • Meaningless pronunciation - correctly sounding out words without meaning There is a hierarchy of miscues, all of which tell you something different about how individual students are creating meaning with print. • A meaningful-miscue is one that does not change the fundamental meaning of the sentence. For example: If the student said, “The dogs run down the road,” instead of “The dogs ran down the road,” this would not change the meaning of the sentences. I recommend that this be counted as half a miscue. Write a large ‘M’ with a circle around it to indicate that it was a meaningful miscue. • A second type of miscue that is of interest, but not necessarily something you need to document is the schema-related miscue. A schema is an organized knowledge structure in long term memory. Schemata (plural of schema) are essential for understanding the world around us as well as learning and comprehending. If a miscue fundamentally changes the meaning of the sentence but is still very much related to the passage, write a large ‘S’ above it with a circle around it to indicate that it is schema-related. It is still counted as a miscue; however, this tells us that the student is engaged in a meaningful reading behavior: using background knowledge. An example of a schema-related miscue include the following: In reading a passage about making roads the students said, “The truck made the road smooth” instead of “The grader made the road smooth.” This is a significant miscue as it changes the meaning of the sentence. A truck is much different than a grader. However, trucks and graders are both used in the making of the road. • A significant miscue is what we most commonly think of as a mistake. Here the miscue changes the meaning of the sentence or does not make sentence within the sentence, the students skips the word, or the student needs help with the word. If the sentence was, “The dogs ran down the road”, and students said, “The dogs rammed down the road,” or “The dogs rode down the road,” these would be a significant miscues as they fundamentally changed the meaning of the sentence. • There is a fourth type of miscue that is not technically a miscue and should not be counted as such. A meaningless pronunciation is when students correctly sound out the word, but it is clear that they have no understanding of the word. You can tell by their inflection if they understand the word. It is often DRA - 7 pronounced in the form of a question. “Fossils?” Or, the individual parts of the word may be pronounced correctly but they are put together in a stilted way or imprecise way. This involves some judgment on your part; however, the power of the DRA is that it provides a structure for you to use your experience and teacher insight to understand students as meaning-makers. If you wish to document this, put an ‘MP’ with a circle around it just above the word. The meaningless pronunciation tells you something about students’ conceptual and word knowledge. There are three possible reasons for a meaningless pronunciation: (a) students do not have a concept to match the word in long term memory, (b) students conception of the word does not match the context in which the word was found, or (c) students were not able to make the link between the word and the concept. This information can be used to design future lessons for both vocabulary and concept lessons. [Question: Make this regular text as opposed to a figure?] Here are the steps for conducting a miscue analysis: 1. Go back and listen to the audio recording of the graded passages. Put a line through the miscued words and write down exactly what the student said on top of the word (include example?). If the student made a miscue but went back and corrected it, it is not counted as a miscue. This is called a self-correction. Self-correcting is a mature reading behavior. This means that the student is monitoring his or her comprehension (metacognition). On your scoring sheet write ‘SC’ with a circle around it on top of the word. SC’s are good. 2. Using the DRA Analysis Sheet in Figure 4.8, write the target word in the first column and what students actually said in the second column. Indicate with a tally mark whether it was a meaningful miscue in the next columns. 3. Significant miscues count as 1 miscue, meaningful miscues count as half a miscue. Do not count proper names as a miscue. If students skip an entire line, count this as one miscue. Add up the total number of miscues. Figure 4.8. DRA Analysis sheet. DRA ANALYSIS SHEET Student: Date: target word Reading level of graded reading passage: miscue meaningful miscue YES NO *Totals Total miscues:_____ Analysis DRA - 8 # selfcorrections fluency WPM comprehension % ind – instr -- frust # total miscues Miscues # not # total miscued words percentage % Patterns or types of miscues (Use the back): * Some reading experts count meaningful miscues as only half a miscue; others do not count them at all. It does not matter as long as you are consistent; however, I recommend counting them as half a miscue. 4. Under the ‘Analysis’ section, record the total number of self-corrections. If a story retelling (below) or comprehension questions were used, record the percentage correctly answered and indication whether it is at the independent, instructional, or frustration level. 5. Determine the reading rate or average words-per-minute (WPM). To do this, record the time it took for students to complete the passage. Divide the time (in seconds) by 60. For example, if you read a passage in 90 seconds, you would dive 90 by 60. 90 ÷ 60 = 1.5 minutes. Divide this (1.5) by the total number of words. If the total number of words was119, Pat read 119 words in 1.5 minutes. 119 ÷1.5 = 79 WPM. 6. Under the ‘Miscues” section of the DRA Analysis Sheet record the total number of miscues. Subtract the number of miscued words from the total number of words to get the number of non-miscued words. To figure out the percentage of words correctly identified divide the non-miscued words by the total number of words and multiple by 100. Use this percentage to indicate general reading levels (98% or better = independent; 90%-97% = instructional; 89% or less = frustration); however, recognize that this only represents word identification (it does not include comprehension). 8. Review the first two columns of the DRA analysis sheet. Look for patterns in the types of miscues students made. Was there a pattern related to beginning, middle, or ending sounds? Vowel sounds? Did certain phonograms give the student trouble? Were they able to identify the beginning sound but not the blend? This will inform the type of instruction needed for word identification. ASSESSING COMPREHENSION In assessing students’ ability to comprehend, keep in mind that students’ ability to read any text is influenced by (a) their familiarity with the topic and the words used, (b) whether it is narrative or expository text, (c) the style of writing, and (d) the construction of the sentences. Described here are two simple ways to assess comprehension. These are used if you are creating your own DRA. Story Retelling DRA - 9 Story retelling is a simple way to get a sense of students’ ability to comprehend narrative text. Use a graded reading passage or story that is at students’ independent level. Identify the important characters, settings, and events in the story and write them in a Story Retelling Chart similar to Figure 4.9 before the assessment. After reading the story, ask students to tell you about the story. As they name each of the items in the Story Retelling Chart, give them one point. If, after retelling the story, they have not named all, ask them directly. Example: “Can you name any other characters in this story? Can you name any other places where this story took place?” Give students one point for correct responses here. If they still cannot name one of the elements, provide a simple hint. These are prompted and worth half a point. Thus far the Story Retelling Chart contains only story details. You can include one or two inference questions. These are questions related to something implied but not specifically stated in the story. These should be worth two points. Figure 4.9. Story retelling chart. Story Retelling Chart Name: _________________________________ Grade: _____ Date: _______ Story Title: ___________________________________ Reading Level: ______ CHARACTERS: 1 point each 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. SETTING: 1 point each 1. 2. 3. EVENTS: 1 point each 1. 2. 3. INFERENCE QUESTIONS: 2 points each 1. 2. TOTAL POINTS: ___/100 = ___% UNPROMPTED PROMPTED ___/100 ___/100 DRA - 10 Unprompted = 1 point Prompted = ½ points Independent reading level = 90%-100% accuracy Instruction level = 75%-89% accuracy Frustration level = 74% or lower Maze A maze can also be used to assess comprehension of narrative or expository text. Use a graded reading passage of approximately 125 to 150 words. After the first sentence, delete every 5th word. Provide three alternatives from which to choose. The choices should include: (a) the correct response, (b) an incorrect response that has the same grammatical function as the deleted word, and (c) an incorrect response with a different grammatical function. There should be 20 total deleted words. Figure 4.10. Example of a maze. Prairie Dogs Prairie dogs are small, burrowing rodents. They live in short-grass [prairies oceans - big] and the high plains [of - in - said] the western USA and Mexico. [They - her - up] will eat all sorts [of -it - many] vegetables and fruits. Independent level = 85% or above Instructional level = 50% to 84% Frustration level = 49% or less PUTTING IT TOGETHER At this point the data should provide you a sense of students’ independent and instructional reading levels. This enables you to determine the level of reading material to use for instruction and the level of books for students’ independent reading. You should also have some diagnostic data to indicate if the student is struggling with fluency, word identification, comprehension, or combinations of these. And finally, you should know what kinds of strategies the student is using to identify words. Three Deficit Areas Readers struggle because of deficits in one or more of the three areas examined by the DRA: fluency, word identification, and comprehension (cite). Fluency. Fluency is the ability to process text quickly and efficiently. Figure 4.9 contains a list of very approximate fluency norms for oral reading rates. The WPM score will give you a very general sense of where the individual student is at in comparison to other students the same grade level; however, your qualitative analysis above will provide a better sense of the student’s ability to read fluently. Figure 4.9. Approximate “norms” for oral reading rates. DRA - 11 At the end of that grade, students should be able to read material at their grade level at the approximate levels below: 1st grade: 53 wpm 2nd grade: 89 wpm 3rd grade: 107 wpm 4th grade: 123 wpm 5th grade: 139 wpm 6th grade: 150 wpm 7th grade: 150 wpm 8th grade: 151 wpm Word identification. Word Identification skills are what students’ use to identify unknown words as they are reading. As described in Chapter 10, there are six general types of word identification skills that students use when a word is not recognized automatically: (a) analogy [word parts or word families], (b) morphemic analysis [prefixes, suffixes, and roots], (c) semantics [context clues], (d) syntax [grammar and word order], (e) sight words, and (f) phonics. Notice that word identification does not simply mean phonics. The qualitative analysis will enable you to determine how students’ identify unknown words, their strengths, deficits, and the types of miscues they tend to make. Comprehension. Comprehension is the ability to create meaning with text. With struggling readers, it is sometimes difficult to know if or to what extent deficits in the areas of fluency and word identification are affecting comprehension. However, the DRA enables you to separate word identification and fluency issues from comprehension. To focus only on comprehension, read the graded reading passage to students and use the Story Retelling Chart to assess comprehension. Planning for Instruction In the chapters that follow, you will be given specific strategies to develop students’ abilities in the three areas above as well as other areas. Three recommendations: First, it is imperative that students not be frustrated or overwhelmed. Chapter 8 describes the negative impact that these emotions can have on students’ learning. Set short, attainable goals (books read or pages read) and make a big deal out of making goals. Instruction should be proximal or just a little ahead of students’ independent level. Second, struggling readers often have difficulties with phonetics. It may seem counterintuitive, but instead of focusing exclusively on what students can’t do as they read, focus on what they can do. That is, plan instructional activities to develop their other two cuing systems (semantics and syntax). Focusing only on letter-sound associations makes reading more-abstract and less-enjoyable. Also, failure increases stress and reduces learning (cite). You can still include word work that develops the phonological cuing system but do not let the other two cuing systems atrophy. Finally, use a comprehensive approach to reading instruction with students that includes the ten essential elements: (a) concepts of print, (b) phonemic awareness [these first two are discontinued once students are reading at the 1st grade level], (c) emotion and motivation, (d) phonics, (e) word identification strategies/skills, (f) fluency, (g) vocabulary, (h) comprehension, DRA - 12 (i) writing, and (j) literature (see Chapter 6). All these elements do NOT need to be included in each lesson. This would be very hard to do. But in your curriculum and over the course of a week, all elements should be addressed to varying degrees. Reliability and Validity Finally, with any type of educational test or measure issues of reliability and validity must be addressed. Reliability in statistical terms refers to repeatability or consistency. How often will you get the same scores or results? For example, if a student scores 98% on the measure one day and 62% on the measure on another day, we would need to consider the reliability of the measure (or the student). Validity refers to extent the test or assessment device measures what it says it is measuring. For example, the language arts portion of an achievement test usually assesses discrete grammar and punctuation skills. It would not be a very valid assessment of students’ ability to write. Just like the Presidential Physical Fitness test would not be a very valid assessment of one’s ability to play tennis. In educational measures there is often a trade-off between reliability and validity. With a DRA, there is some subjectivity built into the measure. It is going to differ slightly from teacher to teacher. However, it is a more valid assessment of students’ ability to create meaning with print than standardized measure because you are observing directly what students are doing as they are creating meaning with print. Bone pile This is why texts with a controlled vocabulary are often difficult for students to read even though they may be identified at the appropriate reading grade level. A story with a controlled vocabulary includes only words that reinforce a particular vowel sound or letter pattern, or texts in which the majority words are from a list of most frequent words used such as Dolch or Fry. The problem with texts using controlled vocabularies is that the language sounds very unnatural, not what students are used to hearing. Remember, we use what is in our head to understand what is on the page. If what is on the page does not sound anything like the language in our head, trying to create meaning with text becomes difficult. Sometimes Lexile levels will be included instead of a RL. The Lexile number is shown as an ‘L’ with a number after it. For example 225L is Lexile level 250. Lexile levels were designed originally to help parents and teachers find books that match students’ independent reading levels. Figure 4.3 contains an approximate Lexile-to-grade-level conversion chart. Figure 4.3. Approximate Lexile-to-grade-level conversation chart. 25L - RL 1.1 350L - RL 2.0 675L - RL 3.9 50L - RL 1.1 375L - RL 2.1 700L - RL 4.1 75L - RL 1.2 400L - RL 2.2 725L - RL 4.3 100L - RL 1.2 425L - RL 2.3 750L - RL 4.5 125L - RL 1.3 450L - RL 2.5 775L - RL 4.7 150L - RL 1.3 475L - RL 2.6 800L - RL 5.0 175L - RL 1.4 500L - RL 2.7 825L - RL 5.2 200L - RL 1.5 525L - RL 2.9 850L - RL 5.5 1000L - RL 7.4 1025L - RL 7.8 1050L - RL 8.2 1075L - RL 8.6 1100L - RL 9.0 1125L - RL 9.5 1150L - RL 10.0 1175L - RL 10.5 DRA - 13 225L - RL 1.6 250L - RL 1.6 275L - RL 1.7 300L - RL 1.8 325L - RL 1.9 550L - RL 3.0 575L - RL 3.2 600L - RL 3.3 625L - RL 3.5 650L - RL 3.7 875L - RL 5.8 900L - RL 6.0 925L - RL 6.4 950L - RL 6.7 975L - RL 7.0 1200L - RL 11.0 1225L - RL 11.6 1250L - RL 12.2 1275L - RL 12.8 1300L - RL 13.5 Not all miscues are the same. There is a hierarchy of miscues, all of which tell you something different about how individual students are creating meaning with print (see Figure 4.4). • A meaningful-miscue is one that does not change the fundamental meaning of the sentence. For example: If the student said, “The dogs run down the road,” instead of “The dogs ran down the road,” this would not change the meaning of the sentences. If the students said, “The dogs race down the road,” this also would not change the meaning of the sentence. I would still count it as a miscue, but I would write a large ‘M’ with a circle around it to indicate that it was a meaningful miscue. If the students said, “The dogs rammed down the road,” or “The dogs rode down the road,” these would be a significant miscues as they fundamentally changed the meaning of the sentence. • A second type of miscue that is of interest, but not necessarily something you need to document is the schema-related miscue. A schema is an organized knowledge structure in long term memory. It is like a file folder in your head used to organize concepts and related knowledge and to make sense of new information and experiences. Schemata (plural of schema) are essential for understanding the world around us as well as learning and comprehending (cite). If a miscue fundamentally changes the meaning of the sentence but is still very much related to the passage, it is still counted as a miscue; however, write a large ‘S’ above it with a circle around it to indicate that it is schema-related. This tells me that the student is engaged in meaningful reading behaviors. An example of a schema-related miscue include the following: In reading a passage about making roads the students said, “The truck made the road smooth” instead of “The grader made the road smooth.” This is a significant miscue as it changes the meaning of the sentence. A truck is much different than a grader. However, trucks and graders are both used in the making of the road. Schema-related miscues are of interest as they provide understanding of the reader’s attempts to create meaning with print. You may wish to document and quantify these on the DRA analysis sheet (see Figure 4.5), but it is not necessary. • A significant miscue is what we most commonly think of as a miscue. Here the miscue changes the meaning of the sentence or does not make sentence within the sentence, the students skips the word, or the student needs help with the word. • There is a fourth type of miscue that is not technically a miscue. It is a meaningless pronunciation. This is when students correctly sound out the word, but it is clear that they have no understanding of the word or what they read. You can tell by their inflection if they understand the word. It is often pronounced in the form of a question. “Fossils?” Or, they pronounce the individual parts of the word correctly but they are put together in a stilted way or in ways in which the inflection or precise sound it not completely accurate. This involves some judgment on your part; however, the power of the DRA is that it provides a structure for you to use your experience and teacher insight to understand students as meaning-makers. If you wish to document this, put an ‘MP’ with a circle around it just above the word. The meaningless pronunciation tells you something about students’ conceptual and word knowledge. There are three possible reasons for a meaningless pronunciation: (a) students do not have a concept to match the word in long term memory, (b) students conception of the word does not match the context in which the word was found, or (c) students were not able to make the link between the word and the concept. This information can be used to design future lessons for both vocabulary and concept lessons. Figure 4.4. Hierarchy of miscues. 1. Meaningful miscue - sentences still retains the original meaning 2. Schema-related miscue - similar concept, sentence meaning not retained 3. Significant miscue - sentence meaning not retained 4. Meaningless pronunciation - correctly sounding out words without meaning A common term for Diagnostic Reading Assessments (DRA) is an Informal Reading Inventory (IRI). The problem with this term is that implies that an IRI may be haphazard or that it may be somehow less valuable than other “formal” types of measures. In the hands of a knowledgeable teacher, a DRA provides far more valuable data than you can get on standardized tests. With the DRA, the examiner is not simply following a formula and list of sequential steps. Instead, the knowledge and experience of the examiner becomes an integral part of the assessment (cite). Figure 4.1 contains a list of common commercially-prepared DRA’s. The information in this DRA - 14 chapter will enable you to use any of these. I will also show you how to design and implement your own DRA’s. Again, these provide a very general sense of the approximate reading grade level of a text or passage. However, keep in mind that students’ ability to read any text is influenced by (a) their familiarity with the topic and the words used, (b) whether it is narrative or expository text, (c) the style of writing, and (d) the construction of the sentences.