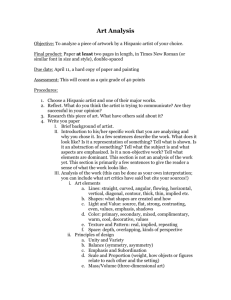

What the Artist Shows

advertisement

What the Artist Shows Steam Railroads in Art 1750-1850 NEH Summer Seminar Aspects of the Industrial Revolution in Britain University of Nottingham 2006 Nancy Sieck, Petaluma High School, California What the Artist Shows • Railroads were originally built to haul heavy cargo from Mines and Foundries to canals and markets. • Passengers took joy-riding excursions behind steam locomotives as early as 1821. • From about 1829, passengers began to make up a larger part of the railroads’ business. • In order to promote their passenger business, railroad companies often had well known artists paint commemorative scenes showing the wonders of steam travel. • When rail travel became more commonplace, publications such as “Punch” satirized the railroads growing importance in their pages. What the Artist Shows Objective view • • Travelling Companions. 1862. Augustus Egg. Birmingham Art Museum. • • The two young women are mirrorimages of each other, they wear grey satin gowns and identical hats with jaunty cockades are perched in their laps. Motion is indicated by the backward sway of the tassel on the window shade. The seaside can be seen outside the window of the carriage. A basket of fruit and a bunch of roses are in the foreground corners. One woman reads, while the other dozes… What the Artist Shows Analysis • • • Travelling Companions. 1862. Augustus Egg. Birmingham Art Museum. • The idyllic scenery along with the elegance of the young womens’ dresses indicates wealth. This leads the viewer to surmise that rail passengers are upper class, or at least in comfortable financial circumstances. The light comes from behind the viewer casting no shadow on the young women, making them appear timeless and carefree, as well as reflecting off the rich fabric of their gowns. Only the tassel sways, indicating that rail travel is more comfortable than road travel. This is also evidenced by the un-rumpled slumber of the young woman on the left. One woman reads, the other slumbers, perhaps indicating the characters of industry and indolence. This painting may have been intended to show prospective investors that rail travel was the way wealthy people got about in comfort. What the Artist Shows Objective View The Night Train. David Cox. 1869. Watercolor. Birmingham City Art Museums • The train just at the low horizon blends in with the heavy clouds, making it difficult to see. • Between the clouds is a bright quarter moon. • Shaggy fell ponies appear startled by the train and one races through the tall grass in the foreground, while the others merely throw up their heads to watch. • There is a gold grassy area in the foreground of the painting on which a dark pony stands. What the Artist Shows Analysis • • • • The Night Train. David Cox. 1869. Watercolor. Birmingham City Art Museums • The low horizon and the speeding train anchors the heavy clouds, drawing the viewers eye from left to right. A quarter moon balances the top third of the painting, allowing the clouds to disappear into mist. Bright light from the moon throws strong shadows behind the pony in the foreground, indicating his importance as onlooker to progress and perhaps his obsolescence. The wind in the grass, the ponies’ flight, the scudding clouds and the rocketing train all indicate speed and movement. Taken together, the painting suggests that speed is of the essence, and mere horses cannot keep up. What the Artist Shows Objective View • • • • First Class. 1854. Daivid Solomon. The Older man in the rear of the compartment slumbers while the younger man and woman talk flirtatiously. Both men are well dressed, as is the young woman. The shade is open and the swinging tassel indicates motion. The carriage is opulent, hence the painting title “First Class – The Meeting”. What the Artist Shows Analysis • • • First Class. 1854. Daivid Solomon. • This painting, originally done in 1854, showing a young man flirting with a young woman while her father sleeps, caused a good deal of social controversy. It was re-painted in 1855 showing the young man and the father talking… no flirting involved. The father’s face, sound asleep, is in deep shadow with his long hair falling about his shoulders in an old-fashioned style. He appears unconcerned and relaxed. All the trappings of speed are apparent in this painting: the swinging tassel, the flashing scenery, and the spirited conversation of the young people. There is a seductive air to the interplay. The artist’s intention was to make rail travel attractive to the young and wealthy, as well as promoting rail travel as a sound financial investment to prospective shareholders . This painting has a similar intent to modern automobile advertising. What the Artist Shows In Addition: • • • • First Class – the Meeting. 1855. David Solomon • This is the second version of “First Class – the Meeting”, painted in 1855 by Solomon. Much less evocative of elegance and youth than the first version, the artist has chosen much lighter colors to evoke brightness and respectability. The young man and the father appear to be doing business in the first class carriage. Their dress and demeanor is much more modern than the previous painting. The young man is no longer in a languid pose This time the young woman is very definitely not part of the discussion, indeed, she appears very timid in the young man’s presence. The difference in lighting is almost more important here than the change in positions of the father and daughter. The entire painting is much lighter – the feeling less clandestine. What the Artist Shows Objective view • • • Perfectly Dweadful. Punch. 27 September 1856, page 124 Punch Cartoon etching showing a Gentleman about to board a train. Guard is showing the gentleman his carriage, which is already quite full. Other people on the platform going about their business carrying parcels and baggage. What the Artist Shows Analysis • • • • Perfectly Dweadful. Punch. 27 September 1856, page 124 Punch cartoons were intended to satirize the ‘Establishment’ and social issues, this one is no exception. Passengers already crowd the railcar, and the foppish gent is dismayed at the prospect of traveling with them. He finds the situation “Perfec’ly Dwedful” Here the British class system is in full view for Punches ridicule, complete with upper-class lisp and contrast of the passengers’ dress. Punch intimates that the lower classes are now encouraged by the rail line owners to ride the trains, but the upper classes still consider the trains their own private kingdoms. What the Artist Shows Objective View • • • • Gustave Doré's illustration of third-class passengers at a station" from London: A Pilgrimage (1872 ). • Etching of the third class section of an underground station, dark in tone, with bright lights casting shadows on the platform. Vanishing point at right center of work. Horizon equally divides the scene into top and bottom. Locomotive and passenger car on the right track, facing the viewer, another train is going in the opposite direction. Both platforms are crowded with working men getting on and off trains. What the Artist Shows Analysis • • • Gustave Doré's illustration of third-class passengers at a station" from London: A Pilgrimage (1872 ) • Not apparently to entice investors to a project or promote rail travel, Dore has given us an extremely photographic representation of public transit in London. The etching is dark because the Underground is just that: underground. The viewer’s eye is drawn to the right rear of the work by the arched light openings and the diminishing perspective of the trains. Third class passengers, mostly working men, crowd the platformsindicating the egalitarian nature of rail travel. Passengers are in overall perspective to the trains and the station,not excessively large or small, lending the sense of reality that is present in all of Dore’s work. What the Artist Shows Objective view • • • • Over the city by railway by Gustave Doré from London: A Pilgrimage. 1872. • Train on the viaduct in the background of a London neighborhood. Very dark etching, with a lighter spot in the center and the arches of another viaduct framing the middle ground. The row of houses curves around to the left center to end below the viaduct Tenement houses are the back-toback variety, showing the yards and wash on the lines. There is a very dark chimney in the right foreground. What the Artist Shows Analysis • • • • • • Over the city by railway by Gustave Doré from London: A Pilgrimage. 1872. On the viaduct in the background, the speeding train blends into the dark, smoky sky. The curve of the houses is a repeated element reflecting the viaduct arches, the house windows, the sag of the clotheslines. Light coming into the scene from the middle right highlights the tenement yards and picks out the sooty laundry. Foreground is dark and the arch seems to close in on the scene, making it almost claustrophobic.The black chimney signifies the pervasiveness of modern industry. The asymmetrical curve of the foreground arch adds an urgency to the etching, perhaps repeating the sense of speed and depressing nature of life portrayed in the work. Doré depicts the way railways cut into the heart of the urban environments, creating dark, bleak neighbourhoods. What the Artist Shows Objective view • • • • Sheet Music.”The Railway Guard, or the train to the North”. Spellman Collection, University of Reading Library. Illustration for sheet music of a contemporary popular song. Black uniformed guard centered on station platform. Rail carriage inside station loading passengers and baggage. Lithograph tinted bright colors. What the Artist Shows Analysis • • • • Sheet Music.”The Railway Guard, or the train to the North”. Spellman Collection, University of Reading Library. Sheet music was a popular genre for commercial art in the 1800s, and publishers often sold their music based on the illustration more than the tune involved. The guard, with his robust, erect bearing and full manly beard evokes an image of strength and competence. Exactly the image the railroads wanted to project. The guard is in contrast to the porter and his heavy burden in the background. Brightly painted green coaches contrast with the yellow of the platform, and the red of the lady’s traveling costume and the nameplate on the coach add a touch of brilliance to the scene. Lofty glass roof over the station adds a sense of protection, and the smoke from the waiting engine conveys power. What the Artist Shows Objective view • • • The original Euston Station, London, dominates this scene. The station is designed as a Greek temple. People and carriages fill the foreground area. What the Artist Shows • • • • The Original Doric columns of Euston Station, London, designed by Phillip Hardwick for the London and Birmingham Railway in 1834, were intended to impress investors and passengers alike. The main arch, imposing in itself, represented a new way of entering the city and drew a forceful analogy between contemporary England and Ancient Rome. While the station was, indeed, very large, the artist’s forced perspective using very small characters makes it seem even more imposing. All the people in the foreground appear in a hurry; speed seems to be diminished and turned to awe as the viewer moves back toward the imposing grandeur of the station. What the Artist Shows Objective view • • • • • George Stephenson on the cover of “British Workman” magazine. Locomotive engine appears above Stephenson. Two railway workers appear on either side of the portrait. Smaller vignettes of industry spawned by the railways are in circular frames at the bottom corners. A story titled “The wonderful Railway Explorer” appears directly below Stephenson’s picture. What the Artist Shows Analysis • • • • George Stephenson was a very powerful man, and this magazine cover portrays him a very positive light. The portrait is enclosed in a round glass-like sphere, much like a crystal ball. In the artist’s view Stephenson and his railroads railroads are the future. The two workmen appear strong, happy, and productive. They are surrounded by their tools. Both the smaller pictures show positive aspects of industry brought about by the power of steam engines, even though they are stationary. What the Artist Shows Objective view • • • • • Jonah Ruskin is portrayed at the center of the drawing with a paint-tube body and palette knife sword. At the left side of the panel lies a railroad train-dragon. The Lady of the Lake appears to the right of Ruskin and her shield, labeled “High Art”, is on the ground a the center of the cartoon. To Ruskin’s right, Lake District scenery is reflected in the water. A white rose, with one petal missing, lies on the ground at Ruskin’s feet. What the Artist Shows Analysis • • • • • • Not everyone was in favor of railroads’ expansion , as shown in this Punch cartoon. Artist and philosopher Jonah Ruskin was vocal about his opposition to the Liverpool and Manchester Railway line’s expansion into Cumbria’s Lake District. Ruskin’s popularity as an artist is evident in his portrayal with a paint-tube body. He has vanquished the locomotive-Dragon to save Britannia’s “High Art”. The mangled rose beneath Ruskin’s feet may actually be the red rose adopted by the L and M as their symbol of patronage. Ruskin was among those firmly against the expanding railroads, particularly what he termed the “vandalism” of homes and national treasures alike. Some of Ruskin’s more famous lines were written against railways and the accompanying frenetic pace of life. He said, “A fool always wants to shorten space and time, a wise man wants to lengthen both.” What the Artist Shows Objective view • • • • The Railway Station, oil on canvas, 1862. William Powell Frith. Passengers waiting for a train crowd the fore and middle grounds. The locomotive and rail cars are in the background. The entire upper half of the painting is the interior roof of the railroad station, composed of two massive arched bays. Departing passengers are well dressed, with a mix of men and women, and children. What the Artist Shows Analysis • • • The Railway Station, oil on canvas, 1862. William Powell Frith • The soaring interior roof of the railroad station, composed of two massive arched bays, suggesting a cathedral. The glass and the ironwork tracery at the rear of the station tell the viewer that this is Brunel’s elegant Victoria Station, even though it is not indicated in the title of the painting. The fine fabrics of the passengers’ dress and the elegance of the station indicates that they are people of wealth. These two facts would be impressive to prospective investors. Pleasant colors of the rich dress fabrics interspersed with the darker mens’ suits give viewers’ eyes stopping places in their travels back and forth through the painting. There is some confusion among the people farther in the background of the painting, where they appear to be rushing toward the cars in the foreground. They may be rushing toward wealth and privilege as well. What the Artist Shows Objective view • • • • • • The Stockport Viaduct, with the tiny silhouette of a Stephenson Locomotive steaming across it fills most of the top half of the painting. Smoke and steam from factories at the left side of the painting mingles with clouds and is split by the Sun’s rays. Two tall, dark factory smokestacks divide the painting in half vertically. Wagons and people crowd the roadway at the left of the painting. On the right, the river flows between the factories and warehouses. Shadow from the buildings and smoke on the left throws the middle ground into darkness. What the Artist Shows Analysis • • • • The viaduct dominates the scene, and the train seems very small in contrast. The artist’s intent was to showcase the architecture of the viaduct. It forms a mighty presence, completely dominating the otherwise important river. Human and wagon traffic on the road at the left is dwarfed by the dark mass of the new factories, their smoke, and the industry they and the train represent. One of the first things the viewer notices is the shafts of sunlight diagonally pointing to the factories, and to the future. The dark vertical smoke stacks are the artist’s “God’s righteous finger pointing the way to Heaven/Redemption”. What the Artist Shows Objective view • • • • • • Great Indian Peninsula Railroad Terminal and Offices, Bombay. 1876. Alex Haig. Oil on Canvas. • Huge, multi-domed building dominates the lower half of the picture. The terrain beyond the building to the left side of the picture is flat and open. Pale blue sky with high, thin clouds. There is a large park in the foreground with trees, fountains and people. British flag flies from the far lefthand side of the building. People are in both the middle and foreground. Some are dressed in European clothing, and others appear to be foreign. There is no indication of industry or a city. What the Artist Shows Analysis • • • Great Indian Peninsula Railroad Terminal and Offices, Bombay. 1876. Alex Haig. Oil on Canvas. • This is a typical “commemorative paining” and does not necessarily show things as they were. The open park shown in front is actually a crowded market square with throngs of vendors and traffic of all sorts. Very few Europeans would have been strolling near the station. The main rail station in Bombay, India was built in the decade between 1878-1888, to be a showpiece of the Raj. It replaced a wooden structure that dated from the early 1830s. The long, unseen rail platforms at the rear, ending in the mass of the station building suggest the floor plan of a secular Cathedral dedicated to progress and modernity. Notice the abundance of glass, and the “Rose Windows” at the front of both large wings. What the Artist Shows Objective view • • • • • St. Pancras Station. c1868 • Gigantic single-span arch dominates the upper two-thirds of the etching. There is a large glass and ironwork partition hanging from the roof at the far end of the station. Light is diffuse, but quite strong in the center of the work. A train is seen approaching the station in the background. Three groups of men appear in the foreground, one of whom is not dressed in work clothes. There is a pool of light at the center of the etching, throwing shadows on the ground. Freight cars are on some of the railroad tracks inside the station. What the Artist Shows Analysis • • • • St. Pancras Station. c1868 • The arched roof at St Pancras Station, London, was a daring design. Single span had never been this large, but Barlow designed the iron structure to be able to support it’s own weight . Note the point to which the ironwork comes at the peak and the lightness of the topmost parts, as compared to the heavier bottom parts. The brick side walls are not structural supports; Scott designed them to appease the Victorian sensibility, but they are really ‘windscreens’. The roof itself was constructed of glass panes, reducing the weight and allowing the space to be flooded with natural light. Originally, rolling stock was stored in the open train shed, but gradually rail traffic dictated that the space be dedicated to additional platforms. The groups of workmen at the center of the work, and the well-dressed businessmen at the right are close to real-size. The station roof, still standing after all these years, is immense. This etching was most likely an encouraging view for investors, an inducement to travel, and a celebration of the station’s daring architecture.