2014-15 - School of Medicine & Health Sciences

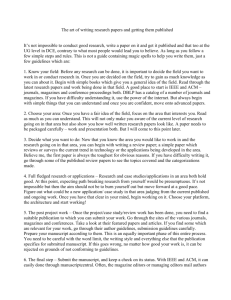

advertisement