Chapter 6 Bambino - Hatboro

advertisement

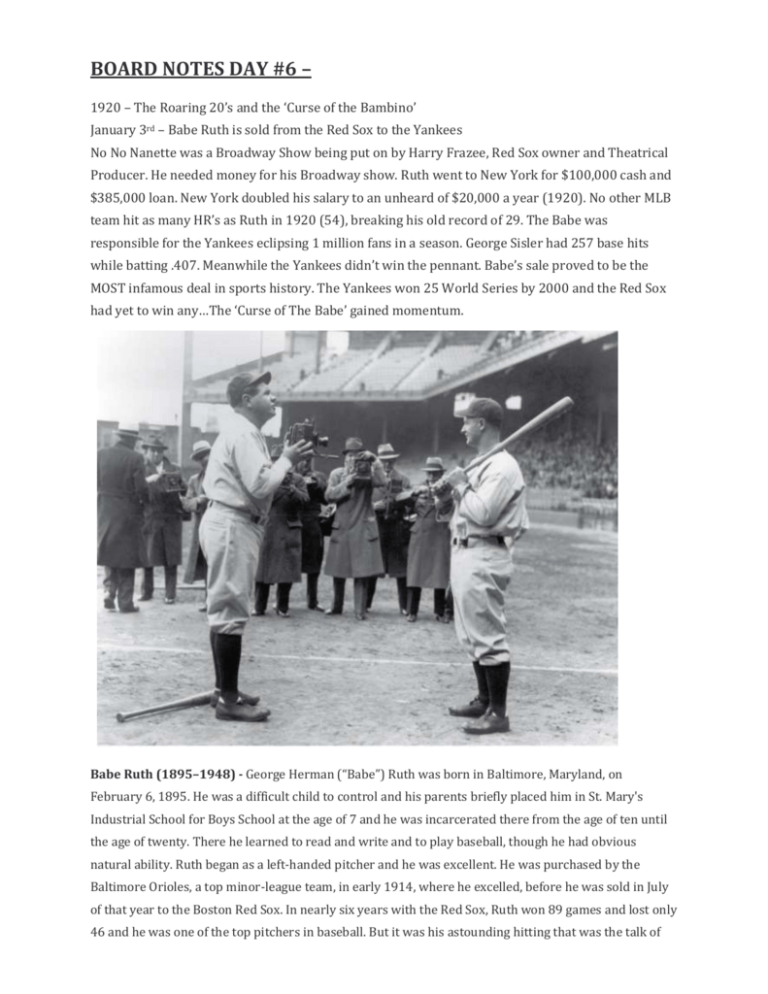

BOARD NOTES DAY #6 – 1920 – The Roaring 20’s and the ‘Curse of the Bambino’ January 3rd – Babe Ruth is sold from the Red Sox to the Yankees No No Nanette was a Broadway Show being put on by Harry Frazee, Red Sox owner and Theatrical Producer. He needed money for his Broadway show. Ruth went to New York for $100,000 cash and $385,000 loan. New York doubled his salary to an unheard of $20,000 a year (1920). No other MLB team hit as many HR’s as Ruth in 1920 (54), breaking his old record of 29. The Babe was responsible for the Yankees eclipsing 1 million fans in a season. George Sisler had 257 base hits while batting .407. Meanwhile the Yankees didn’t win the pennant. Babe’s sale proved to be the MOST infamous deal in sports history. The Yankees won 25 World Series by 2000 and the Red Sox had yet to win any…The ‘Curse of The Babe’ gained momentum. Babe Ruth (1895–1948) - George Herman (“Babe”) Ruth was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on February 6, 1895. He was a difficult child to control and his parents briefly placed him in St. Mary's Industrial School for Boys School at the age of 7 and he was incarcerated there from the age of ten until the age of twenty. There he learned to read and write and to play baseball, though he had obvious natural ability. Ruth began as a left-handed pitcher and he was excellent. He was purchased by the Baltimore Orioles, a top minor-league team, in early 1914, where he excelled, before he was sold in July of that year to the Boston Red Sox. In nearly six years with the Red Sox, Ruth won 89 games and lost only 46 and he was one of the top pitchers in baseball. But it was his astounding hitting that was the talk of baseball and he began to pitch less and play the outfield more. In 1919 he went 9–5 as a pitcher, but hit twenty-nine home runs, an astonishing total for the time. The next highest total was ten. In 1920 Ruth was sold to the Yankees by the Red Sox owner, Harry Frazee, for $125,000, the highest amount ever paid for a player. It turned out to be a bargain as Ruth led the league in home runs numerous times on his way to setting what was the record for career home runs of 714. He also compiled a lifetime batting average of .342. More important was the fact that Ruth led the Yankees to 7 pennants and 4 World Series titles in his 15 years as a Yankee. He was one of the first five players elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1936. Ruth also was the most well-known figure in sports and appeared in films, had his own basketball team in the off-season, and was famous for just being himself. He was a prodigious consumer of food, drink, cigars, and good times. In the early years of the Great Depression he had a salary of $80,000, more than the president of the United States, and his overall income was much higher. When questioned about this by a reporter, Ruth said, “I had a better year.” He is still one of the most recognizable of sports figures, 64 years since his death in 1948. Other – American Professional Football Association (APFA) founded in Canton, Ohio at the Jordan and Hupmobile Automobile Showroom. Jim Thorpe named 1st president. Thorpe played inaugural season for the Canton Bulldogs. The United States had grown to 106 million by 1920, and during the decade the population would rise to just over 123 million. The 1920s were a marked contrast to the decade that had just ended. World War I had been extremely destructive for Europe, but the United States escaped unscathed and was now, clearly, the world leader in economics and was almost as powerful as Great Britain and its enormous empire. With the onset of the 1920s two great social changes took place with the implementation of the 18th and 19th amendments to the U.S. Constitution, which mandated legal prohibition of alcohol for consumption in the United States (18th) and prohibited denial of the franchise (voting) on the basis of gender (19th). Prohibition remained in effect for 14 years, finally being overturned in 1933 with the passage of the 21st Amendment. During the 1920s the consumption of alcohol actually rose as its distribution was no longer regulated by the government. Many people turned to distilling, distributing, or selling alcohol, thus making a large number of criminals in the American populace. Alcohol was brewed by some people who did not understand, or care, about safety in the distilling process. As a result many people who consumed this improperly brewed product died. The trafficking in illegal alcohol brought organized criminal gangs into the alcohol business. Such gangs were led by people like Al Capone, who made millions from such illegal businesses, but wound up in jail after being convicted of income tax evasion. Most alcohol was served in speakeasies, secret clubs that were hidden within cities and towns. Since it was hard to keep their locations secret because customers needed to know where to find the clubs, speakeasy owners often had to bribe police or public officials to “look the other way” and pretend that they were unaware of the presence of these drinking establishments. Such scenarios were carried out across the country, creating a whole new breed of “scofflaws,” people who openly failed to follow laws with which they disagreed. Though the public consumption of alcohol was illegal, the lack of sales at sports venues, especially baseball games, seemed to have little effect on attendance. Sports were entering what has been termed a ‘golden age’ in the 1920s since people had peace, leisure time, and more disposable income. Spectator sports, especially baseball, horse racing, boxing, and college football, were the biggest draws and beneficiaries of the new, nationwide interest in sports. The 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote for the first time in federal elections. Some states had granted the franchise as early as 1869 when Wyoming granted women the franchise. Colorado followed in 1893. The motives of the voters of these states were not totally altruistic. Most of the West was very rough and undeveloped and there was a decided lack of single women. The enticement of being able to vote was seen as an inducement to gain a larger female population in these states. Women had not been given the right to vote in the Constitution when it was first ratified in 1788. Women were not often well educated since only the poorest women would actually have worked outside the home. Women were often idealized by the ruling classes, but that idealization included neither education nor decision making. Basically, the society of the time was sexist, denying women almost every basic human right under the pretext of protecting them. It certainly would have been difficult for a woman to be successful on her own at that time, since society was not structured in a way to allow it. As more and more women received basic education, there were more opportunities for women to go on to academies and, for some, even higher education, though these instances were not usual. By 1900 most middle-and upper-class women had completed elementary school and were certainly capable of making informed decisions, at least as informed as many men who might not have attended school at all but were still allowed to vote because of their gender. When female suffrage finally was passed in 1920, it was not without a great deal of resistance. In 1920, the first federal election for which they were eligible, fewer than half the eligible women voted, and in 1924 the estimate was that onethird of eligible women voters had gone to the polls, as opposed to two-thirds of eligible male voters. The percentage of women voting slowly increased throughout the decade, particularly as women began to identify with, and be courted by, the political parties. This initial reticence by many women to go to the polls was also seen in their reluctance to attend major sporting events. Of course, most men were attending such events with other male colleagues and, in the case of baseball, many came to games directly from their places of employment for games beginning at 3 P.M. Horse racing and boxing saw more women attendees, although women were initially barred from the latter events in many states because of the violence. The election of 1920 pitted Republican senator Warren G. Harding against Democratic governor James Cox, both of Ohio. Harding promised a “return to normalcy” (though there was no such word; the proper word was “normality”) and he appealed to people who had grown weary of the war in Europe and longed for a quieter time. Harding won in a landslide, with 60% of the vote, but he was not a very engaged president. He appointed some excellent Cabinet secretaries, but he also was largely unaware of corruption in his administration. Many scholars consider him the worst U.S. president and he died suddenly of a heart attack in 1923. Harding was succeeded by his vice president, Calvin Coolidge, a former governor of Massachusetts. Coolidge was a laissez-faire president, that is, he didn't see any reason for the government to be deeply involved in the business of the nation. In fact, he said, “the business of America is business.” Some link this view and practice to the resultant Depression of the 1930s. Coolidge was very popular and seen as a real populist, like one of the “regular” people, and he swept to victory in 1924 with 54% of the vote versus 29% for Democrat John Davis and 16% for progressive Robert M. LaFollette. Coolidge was known as “Silent Cal” because of his taciturn nature. In 1928 he chose not to run for re-election and former Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover became the 3rd Republican victor in a row when he defeated Democrat Al Smith of New York in that year. Many Americans feared voting for Smith because he was a Catholic and they thought that American policies might be subject to approval or scrutiny of the Roman Catholic Church and its leader, the pope. This mistrust was still evidenced until 1960 when John F. Kennedy won the presidency. The prejudice toward Catholics (as well as Jews and African Americans) was widely publicized and practiced by a number of hate groups, the most widely known being the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). The Klan had begun in the mid-19th century, but had largely vanished until it was resurrected in 1915. At its peak in the early 1920s, membership was about 15% of the nation's eligible male voters, or about 4–5 million men. The decade also had great technological changes, which altered the way people received information. Most specifically, the radio became a medium for citizens, with the first regular broadcasts during this decade. Radio helped transform many areas of American society, among them sport. The first radio broadcast was on November 2, 1920, when the returns of the Harding-Cox presidential election were carried on KDKA, Pittsburgh. Radio usage started slowly but accelerated astronomically in middecade. In 1926 the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) was formed through the connection of 24 stations. The Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) followed in 1928. Congress passed the Radio Act of 1927, which established the Federal Radio Commission, which would create and police regulatory guidelines for broadcasting in the United States. Television broadcasting was first experimented in the late 1920s, but it would not be until after World War II that television would become a common broadcasting medium. The radio became the medium of choice for many sports fans during the 1920s. The radio created new fans and increased casual fans' interest as play-by-play coverage of baseball, boxing, and college football became commonplace. Certainly the creation of the biggest sports heroes of the period was the result of the adulation by radio announcers, many of whom, like Graham McNamee, became heroes in their own right. Automobile ownership grew tremendously during the decade and this influenced the construction of better roads, subsequently making it possible for Americans to be more and more mobile. Henry Ford's Model T was an assembly-line model that allowed few deviations, but drove costs way down. This made automobiles affordable to many families and the 1920s became the first automobile decade. By 1927 more than 15 million Model Ts had been sold in the United States. By 1929 nearly half of all American families owned a car. The automobile allowed many fans to attend games more easily; the biggest beneficiary was probably college football. Alumni and other football fans could now drive to big games and return in the same day. The best examples were the enormous followings that Red Grange and the University of Illinois squad and Coach Knute Rockne and his University of Notre Dame teams inspired. Fans from Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, and Indianapolis (just to name a few urban centers) now regularly drove to the games in Champaign or South Bend, backing up the highways for miles. New stadiums were built, reflecting both increased popularity of sport and the ease of access, such as the University of Illinois's Memorial Stadium, the University of Michigan's Stadium, and that of the University of Notre Dame. All were opened between 1923 and 1930 with capacities of more than 50,000 and were filled each football Saturday. Still, trains were the most efficient way to travel any great distance. Railroads criss-crossed the eastern half of the United States; the northeastern quadrant had the most track and rail systems. Long-distance travel was dominated by the railroads since roads were not universally well maintained and commercial airplane travel did not really become established until the 1930s. Most airline companies were formed for and carried U.S. mail. Pan American World Airways began in the 1920s with passenger service, but that was limited. Almost all sports teams traveled by train, which was far more comfortable than other modes of travel at the time. Train compartments were spacious and the food good. Players had room to stretch out and there were cars where they could play cards, eat, and smoke (which many of them did). Not until the late twentieth century, and the onset of charter or privately owned team planes, would teams begin to fly. One of the greatest American heroes of the period was Charles Lindberg, who became the first person to fly solo, nonstop, across the Atlantic in 1927. His feat did not send people clamoring to fly to Europe, but it did show that long-distance air travel did have a commercial future in the United States and the world. Cities had extensive trolley systems that linked much of an urban area and allowed citizens to travel easily within the urban confines to attend various sports events. Most immigrants lived in urban areas and many of their children became caught up in sports, often mystifying their parents, who had little leisure time for sports in their native countries and were unlikely to engage in those in the United States. The U.S. economy seemed to be constantly on the upsurge during most of the 1920s. The early years of the decade saw job cuts and strikes, but as the 1920s continued, the economy grew, corporate profits increased dramatically, taxes were cut, the building trades boomed, and the forty-hour workweek was instituted. The greatest economic gains were by the wealthiest Americans. For the poorest workers, gains were minimal, if seen at all. During this time sports stars' salaries rose dramatically against that of the average worker and some of the greatest stars like Babe Ruth were paid what were seen as astronomical sums. Ruth's $80,000 salary in the early 1930s exceeded that of the president and astonished the fans, though most did not begrudge the Babe receiving this enormous amount. Red Grange's entry into professional football also entailed an enormous amount of money, previously unheard of for a pro football player. Fans flocked to the stadiums to see these superstars who were receiving super salaries. The collapse of the stock market in October of 1929 brought American prosperity to a halt. Unemployment rose from 500,000 in October to more than 4 million in December and it continued to worsen into most of the 1930s. Arts in the 1920s were exciting and innovative. George and Ira Gershwin created hundreds of wonderful songs and musicals including Strike Up the Band, Funny Face, Girl Crazy, and Pardon My English. Of more renown were George Gershwin's fabulous Rhapsody in Blue, An American in Paris, and the opera Porgy and Bess. Irving Berlin wrote classic songs and Martha Graham produced creative dances. The Harlem Renaissance flourished at this time, which provided for a wealth of innovative African American art, music, dance, and literature. Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and Zora Neale Thurston were the best-known writers, while jazz/blues greats like Bessie Smith, “Jelly Roll” Morton, Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong began their careers. The first talkie movie was made in 1927, The Jazz Singer, starring Al Jolson. The Gershwin’s, Jolson, and Berlin were all the children of Russian Jews who had emigrated to escape the pogroms of Eastern Europe and sought the freedom of the United States. 3 sports dominated fans' interest during the 1920s: baseball, boxing, and college football. Horse racing, tennis, and golf also had some significant appeal. Both professional basketball and professional football were in their infancy at this time, but they had some rabid adherents. One general comment on the media is necessary. Radio was new in the 1920s, but was amazingly common in most homes by the end of the decade. There were far more newspapers than today, especially in big cities, where there might have been five to ten daily papers, many of which had three or four editions printed per day. One of the most common sources of information, particularly providing images, was the movie newsreel, short films of various events shown in movie theaters with new films each week. Though the stories were short and sometimes a bit quirky, these newsreels were the only time that most Americans would have actually seen and heard moving images of politicians and sports heroes. Babe Ruth, Red Grange, Bobby Jones, Knute Rockne, top boxing matches, major horse races, and the World Series were all subjects in these newsreels. In addition, short films were sometimes made featuring top sports stars like Babe Ruth. These, too, made such figures more familiar to Americans, often more so than the president.