semLecture6

advertisement

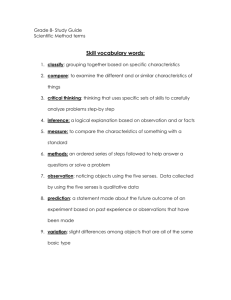

Introduction to Semantics Lecture 6 Albert Gatt Linguistic Relativity: meaning and thought (From last week) Contemporary research: Numerical cognition The number sense Rationale: 1. Suppose language L2 only distinguishes quantities in a very basic way e.g. “one” vs. “many” 2. Then, we can ask whether speakers of L2 are capable of abstract quantitative reasoning like other speakers. 3. If not, then there must be an influence of language over mathematical cognition. Semantics -- LIN 1180 Peter Gordon’s work Gordon (2004): investigated these questions among the Piraha tribe in the Amazon Piraha distinguishes “one”, “two” and “many”. No terms for “twenty”, “thirty-three” No recursive devices for forming complex numbers (“one hundred and one” etc) Semantics -- LIN 1180 Some observations on Piraha The three words for “one”, “two” and “many” are used as prototypes: hói (“one”): typically for one objects, but often also used for “a few” hoí (“two”): typically for 2 objects, but also for “a relatively small quantity greater than hói” aibaagi (“many”): for any number of objects which are “a lot” Semantics -- LIN 1180 Experimental task (example) 7 participants in a matching task Experimenter sits opposite participant places a linear array of objects on a table participant has to match the array with his own objects (a kind of substitute for counting) Semantics -- LIN 1180 Matching task: results If the array consisted of between 1 and 3 objects, participants were reasonably accurate. With greater numbers, performance became increasingly inaccurate. Tendency became more pronounced with more complicated versions of the task. Semantics -- LIN 1180 Gordon’s conclusions “The results of these studies show that the Piraha’s impoverished counting system limits their ability to enumerate exact quantities when set sizes exceed two or three items.” (2004, p. 498) Semantics -- LIN 1180 Some reflections on Gordon (2004) Gordon’s study was restricted to a small set of individuals. Not very controlled environment. It has sparked off a considerable debate about: whether “all languages are equal” whether language has a “conditioning” effect on thought: Can we not think things which we cannot name? Semantics -- LIN 1180 Some reflections on Gordon (2004) Gordon’s work goes beyond words: languages like English have simple number words (one, two…) but also grammatical systems which allow these words to be combined (one hundred and one….) If Gordon’s observations are correct, then grammar may have a role to play in thinking: grammar may be a way of combining simple concepts into complex ones. Semantics -- LIN 1180 Part 1 The domain of lexical semantics Goals of this lecture By now, we have introduced some of the major concepts and positions in semantic theory. This lecture begins our incursion into Lexical Semantics: Word meaning The structure of the mental lexicon Lexical relations Knowledge of words What does it mean to “know” a word? Iltqajt ma’ ziti (I met my aunt) Iltqajt ma’ mara (I met a woman) Zija/Aunt entails woman/mara Ġanni qatel lil Pietru (John murdered Peter) Pietru miet (Peter died) Qatel lil x / kill x entails x miet/x died These entailment relations suggest that when we know a word, we also know several connections to other words. Part of the concern of lexical semantics is to characterise this knowledge. Representing lexical knowledge (Reminder from previous lectures) The word aunt is somehow related to the word woman: Theory of necessary and sufficient conditions: WOMAN is part of the meaning of the definition of AUNT in our mental lexicon Lexical taxonomies: There is a hierarchical relationship, where WOMAN is the superordinate of AUNT The units of analysis: words If we’re going to talk about word meaning, we need to identify what a word actually is... Not as easy as it seems Preliminary semantic definition: A word represents a “unit of meaning” Definition of a word (I) Orthographic: Anything we write separated by whitespace Phonological: Any string of sounds which has some internal structure that distinguishes it from other parts of a speech signal E.g. We often find pauses at word boundaries Definition of a word (II) Grammatical definition: Words are the basic input to syntax. They are the minimum free form (Bloomfield 1933) Words can occur in isolation They can differ according to their grammatical category and inflectional features kiel eat-3MSg-Perf. kilt eat-1Sg-Perf kielet eat-3FSg-Perf kielu eat-3Pl-Perf In English, all these different forms would qualify as a single grammatical word I/He/She/They ate Definition of a word (III) An intuition: The words kilt/kiel/kielet etc are all different forms of a single semantic word, meaning the action of eating By convention, Maltese uses the 3rd Person Sg. Masc as citation form: kiel English uses the infinitive or –ing form: to eat/eating One way to capture the grammatical/semantic distinction is by distinguishing types and tokens kilt/kiel/kielet etc are tokens of the same type kiel, meaning EAT Problems with identifying words Semantic definition is problematic: English puce = Maltese vjola ċar Maltese ngħid = English I say Not every “semantic word” in one language is a semantic word in another Grammatical definition might be better but: There are things that don’t occur in isolation which speakers still classify intuitively as words: Is the Maltese definite article a word? Il- is phonologically noun (a clitic) dependent on the We’re just going to assume that we know what a word is, but be mindful of the pitfalls! Part 2 Words, word senses and context Word senses Consider: I hurt my foot bodypart the foot of the mountain bottom of high incline These are different senses, but they are related: they both denote to the “base” of something Or: Kiser spalla minnhom (he broke a shoulder) Again, related: the “tree” sense is derived from the “bodypart” Għamlet sajjetta u faqqgħet spalla mis-siġra sense. bodypart (a lightning bolt broke off the main branch of a tree) main branch of a tree Word senses (II) Different senses of a word are semantically related Grouped together in a traditional dictionary, in one lexical entry Spalla n.f. (pl. spalel) 1. shoulder 2. one of the main branches in a tree (Aquilina, J. Concise Maltese-English Dictionary) Foot n. (pl. feet) 1. part of the leg below the ankle. 2. base or bottom of something Word Senses (III) Lexicographers make these entries using a number of conventions: Parts of the entry have the same grammatical category Senses in a lexical entry share a number of semantic properties. Different senses may be historically related. spalla (= tree branch) is derived from spalla (= shoulder) Problems with pinning down senses It’s not always clear whether a word: has different senses, as in the case of foot has only one sense, but exhibits “shades of meaning” Part of the problem is that word meanings have contextual dependencies Context (I): Collocation Context can distinguish words with nearly identical meaning (near-synonyms) E.g. the adjectives big, large, great A traditional dictionary (OED online): large adj. of considerable or relatively great size, extent, or capacity big adj. of considerable size, physical power, or extent great adj. of an extent, amount, or intensity considerably above average Context (I): Collocation Typical contexts of use for big: with concrete nouns: big man, big house with descriptive adjectives: big black rat… Typical contexts of use for large: with abstract nouns: large number, large scale, large ratio, large amount Typical contexts for great: great importance, great deal, great variety… NB: some of these contexts are shared. But some adjectives occur more frequently in some contexts. Context (I): Collocation Word combinations exhibit degrees of collocational strength Often a result of frequency of usage. The adjective great became more strongly collocated with deal than large or big This is a kind of fossilisation: Two words have (apparently) the same meaning, but their patterns of usage become fixed over time. Context (II): Meaning shift Sometimes, the same word can display different “shades of meaning” in different contexts Consider the patterns of occurrence of qawwi (“strong” or “powerful”) Can you think of examples which show differences in meaning? Context (II): Meaning shift The word qawwi in different contexts: raġel qawwi = “big man” baħar qawwi = “rough sea” te qawwi = “strong tea” investiment qawwi = “a substantial investment” maltemp qawwi = “very stormy weather” ġebel tal-qawwi = a kind of limestone These contexts seem to “pull apart” different meanings of the same word. Context (II): meaning shift The 6 different uses of qawwi: Are these different semantic words? Are they five senses of the same word? (Aquilina lists 13 different senses) Different uses have a lot in common: Qawwi always carries a notion of “strength” Part 3 Ambiguity and vagueness Ambiguity A word is ambiguous if it has several distinct senses. 2 & 3 both involve the physical act of running. Example 1 has a specialised meaning Example 1 (English): 1. I built a run for my chickens. 2. I go for a run before work. 3. I hit a home run during the cricket match. Example 2 (Maltese): 1. Kibt id-daħla tal-ktieb. (= “I wrote the introduction to the book”) 2. Hemm daħla fil-bajja. (= “The bay has an inlet”) 3. Qed jirrestawraw id-daħla tal-Birgu. (= “They’re restoring the entrance/city gate of Birgu”) 2 & 3 both denote some kind of entrance. Example 1 has a specialised meaning. Ambiguity vs. Vagueness (I) In context, a word can seem to have several distinct senses. Some may appear more related than others. In our example: run1 = physical act of running run2 = place where fowl are kept So run is 2-ways ambiguous (2 senses) But run1 exhibits vagueness between a general sense of running, and the more specialised sense used in cricket. Ambiguity vs. vagueness (II) Similarly: daħla1 = entrance or inlet daħla2 = introduction to a text 2-ways ambiguous daħla1 is vague between the sense of “entrance” and that of “inlet” Ambiguity vs. vagueness (III) ...and for another example: There’s a mole in my garden mole1 = small, furry animal living underground There’s a mole in the CIA mole2 = a spy We can say that mole is 2-ways ambiguous Ambiguity vs. vagueness (IV) Ambiguity: In this case, the context will select one of the meanings/senses We often don’t even notice ambiguity, because context clarifies the intended meaning. Vagueness: Context adds information to the sense. Therefore the sense of the word itself doesn’t contain all the information. It is underspecified. Tests for ambiguity and vagueness There are some tests to decide whether meaning distinctions involve ambiguity or vagueness. The do-so test of meaning identity The synonymy or sense-relations test The do-so test: preliminary example I ate a sandwich and Mary did so too did too The do-so construction is interpreted as identical to the preceding verb phrase Similar constructions in Maltese: Kilt biċċa ħobż u anka Marija Kilt biċċa ħobż u Marija għamlet hekk ukoll. The do-so test and meaning identity Main principle: if a particular sense is selected for a word in a verb phrase, it will also be the same sense in the do-so phrase Therefore, very useful to test if two meanings are two distinct senses. Do-so examples Lili għoġbitni d-daħla u lil Jimmy wkoll (I liked the entrance/introduction and so did Jimmy) Suppose daħla here = “introduction” Is it possible that I liked the introduction and Jimmy liked the entrance? If not, then these are two distinct senses or daħla I made a run and so did Priscilla If “I made a run” = “I ran”, then Priscilla cannot have made a run for her chickens... So, again, these are two distinct senses of run. The sense relations test Basic principle: Words exhibit synonymy or similarity of meaning to other words. Therefore, if a word is ambiguous, we can substitute it for a similar word in the same context, and see if the meaning stays roughly the same. Sense relations examples Recall: run1 = physical act of running (similar word: jog) run2 = a closed space for animals (similar word: enclosure) Pete went for √ a run . √ a jog *an enclosure We can’t substitute one set of words for another and still keep the same meaning. Summary Started off with different definitions of a word: semantic, grammatical... Introduced the notion of a word sense Discussed the notions of ambiguity (several word senses) and vagueness (single sense, with slight variations in context) Next lecture We continue our investigation of lexical semantics by delving into lexical relations