vol45-2008 - Minnesota State University, Mankato

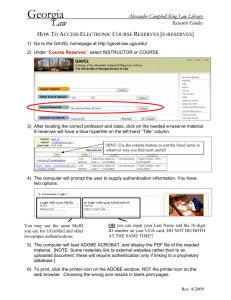

advertisement