The upper motor neuron syndrome and spasticity: Pathophysiology

advertisement

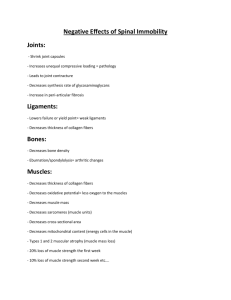

THE UPPER MOTOR NEURON SYNDROME AND SPASTICITY: PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT ROBERT J. CONI, DO NEUROLOGY – GRAND STRAND REGIONAL MEDICAL CENTER LEARNING OBJECTIVES After this discussion, the participant should be able to: • Define and differentiate spasticity from other neurological conditions associated with increased tone and be able to articulate the intricacies of various treatment options available. • Relate the various presentations and be able to outline appropriate treatment measures depending on the presentation. • Define and appreciate the full range of treatment options available. • Appreciate the natural history and progression of spasticity including the causes, consequences of the insult and the added effects of disuse of the affected region. • Understand the various modalities of chemodenervation and where, when they are applied. • Appreciate the pharmacology of applicable oral agents including; indications, side effects and use of these agents. EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PREVALENCE OF SPASTICITY • Spasticity affects > 12 Million people worldwide. • Prevalence estimates vary and are specific to the associated conditions and/or etiology. • 19% of persons 3 months after a stroke. • 17% of persons 1 year after a stroke. • 4% with disabling spasticity. • 38% of persons 1 year after a stroke. • Arms and legs affected. • 42% of persons 1 year after a stroke. • Usually multiple joints affected. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF SPASTICITY • One of several components of the Upper Motor Syndrome. • Causes: • Stroke • Brain or Spinal Cord Injury • Cerebral Palsy • Multiple Sclerosis FEATURES OF SPASTICITY AND SPASTIC PARESIS • Spasticity is one type of “muscle overactivity” which needs to be distinguished from other components of the syndrome including dystonia and rigidity. • Muscle overactivity, soft tissue shortening and paresis are the 3 major disabling factors in spastic paresis of the UMN syndrome. • Spasticity and muscle overactivity cause disability, interfere with ADLs and may cause pain and immobility. NATURAL HISTORY OF SPASTIC PARESIS ACUTE CNS Damage Paralysis Immobilized and shortened DELAYED T FACTORS IN THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF SPASTIC OVERACTIVITY • SPINAL • Enhanced excitability of monosynaptic pathways caused by multiple changes in reflex activity. Increased muscle spindle stimulation in stiffer muscles; α motor neuron excitability; presynaptic inhibition on group Ia afferents, group Ib inhibition, group II pathways, Renshaw cells and reciprocal group Ia inhibition. • SUPRASPINAL • Release of activity in excitatory brainstem descending pathways causing dystonic posturing. • A hemiplegic posture develops, where antigravity muscles in particular are stimulated by motor neurons which develop overactivity. POST IMMOBILIZATION JOINT ROM LIMITATION • Immobilization in the shortened position results in less longitudinal tension (unopposed) producing contracture. • Muscle contracture – results in • Atrophy • Loss of sarcomeres (shortening) • Accumulation of connective tissue • Increase in spindle responsiveness NATURAL HISTORY OF SPASTIC PARESIS DELAYED ACUTE CNS Plastic Rearrangements *Spinal *Supraspinal CNS Damage Paralysis Disuse Immobilized and shortened Soft Tissue Plastic Rearrangements Muscle Overactivity Spasticity Spastic contraction Dystonia Others T COMMON TYPES OF MUSCLE OVERACTIVITY IN UMN SYNDROME • SPASTICITY • Velocity dependent increase in response to phasic stretch in absence of volitional command (ie., at rest). • Clasped knife response • SPASTIC DYSTONIA • Stretch sensitive tonic muscle contraction in absence of volitional command (ie., at rest), including command to neighboring or distant muscles, and in the absence of phasic stretch of that affected muscle. • SPASTIC CO-CONTRACTION • Inappropriate antagonist recruitment triggered by volitional command during effort of an agonist in absence of phasic stretch. MUSCLE STRETCH REFLEX MUSCLE PHYSIOLOGY CHARACTERISTICS SIGNS OF THE UMN SYNDROME Positive Signs Negative Signs • SPASTICITY (Increased muscle stretch reflexes) • MOTOR WEAKNESS • SPASTIC DYSTONIA • MUSCLE FATIGUE • SPASTIC CO-CONTRACTION • LOSS OF SELECTIVE CONTROL OF SPECIFIC MUSCLES • RELEASED FLEXOR REFLEXES • ASSOCIATED REACTIONS (SYNKINESIS) • RHEOLOGIC CHANGES: INCREASED MUSCLE STIFFNESS AND CONTRACTURE FORCES THAT GENERATE UMN SYNDROME PATTERNS Extensors Flexors A combination of positive and negative signs and rheologic changes in muscle produce the common patterns of UMN dysfunction UMN PATTERNS GENERATED BY DYNAMIC AND STATIC FORCES UPPER LIMB LOWER LIMB • Adducted, internally rotated at shoulder • Flexed hip • Flexed elbow • Flexed knee • Pronated forearm • Stiff knee • Flexed wrist • Equinovarus or equinus foot • Clenched fist • Hyperextened hallus • Thumb-in-palm • Flexed toes • Adducted thighs ADVERSE EFFECTS OF MUSCLE OVERACTIVITY • SLOW VOLUNTARY MOVEMENTS DUE TO SPASTICITY • IMPAIRED STANDING BALANCE • IMPAIRED COORDINATION • IMPAIRED SLEEP • SKIN SHEER AND BREAKDOWN • RISK OF CONTRACTURES • IMPAIRED PERINEAL HYGIENE AND SEXUAL FUNCTION • POOR BED AND WHEELCHAIR POSTURES • DIFFICULTY DRESSING • IMPAIRED GAIT • PAIN CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF THE UMN SYNDROME • SYMPTOMATIC COMPLAINTS • PROBLEMS OF PASSIVE FUNCTION • Personal care • Positioning • PROBLEMS OF ACTIVE FUNCTION • Limb use • Mobility CONSEQUENCES OF SPASTICITY • POSSIBLE MEDICAL COMPLICATIONS • Contracture, Fibrosis, Muscle atrophy • NEGATIVE IMPACT ON PATIENTS AND CAREGIVERS • Reduces mobility and impedes activities of daily living • OFTEN POORLY TREATED AND MISMANAGED • Inadequate assessment guidelines • Lack of specialized spasticity management • Treatment not individualized • Inappropriate treatment selection • Insufficient follow-up ASSESSMENT ALGORITHM FOR MUSCLE OVERACTIVITY Patient presents with muscle overactivity EVALUATE PATIENT Does the muscle overactivity significantly interfere with function or will it lead to musculoskeletal deformities NO YES Patient and Caregiver objectives Functional objectives Initiate comprehensive treatment program Technical objectives ASSESSMENT OF SPASTICITY INSTRUMENT MEASURED • 3D Gait analysis • Goniometric ROM • Functional measures CLINICIAN REPORTED PATIENT/CAREGIVER REPORTED • Muscle tone (modified Ashworth scale and Tardieu) • QOL • Physician gait ratings • Satisfaction/preference • ROM of joints • Participation/impairments • Global outcome measures • FIM • Barthel index • Dependence • Disability scales • Functional status CLEAR OUTCOMES MEASURES NEEDED • NO GENERAL CONSENSUS • Systematic review of botulinum toxin use in patients with cerebral palsy demonstrated that outcomes tend to focus on spasticity or ROM and not activity or function. • There have been conflicting reports of use of the modified Ashworth scale to assess lower limb spasticity. • Inter rater reliability and longitudinal rating reliability are poor. • Thus, Ashworth scale lacks validity and reliability to measure spasticity. IMPORTANCE OF SPASTICITY TREATMENT • WHEN UNTREATED OR INADEQUATELY TREATED, THERE CAN BE LONG TERM HEALTH CONSEQUENCES • Pain • Bladder and bowel dysfunction • Deformity • Contracture • Compromised cognitive function due to fatigue • NONPHARMACOLOGIC OPTIONS TO TREAT MUSCLE OVERACTIVITY • Physical and Occupational therapy • Surgical interventions OBJECTIVES IN TREATING MUSCLE OVERACTIVITY IN UMN SYNDROME IMPROVE QUALITY OF LIFE • Relieve symptoms and reduce disfigurement • Ease personal care and positioning (passive function) • Improve limb function and mobility (active function) • Enable activities of daily living • Reduce burden of care MANAGEMENT INTERVENTIONS FOR MUSCLE OVERACTIVITY Evaluation Physical Therapy Occupational Therapy Goals Reevaluation Intrathecal Medication (Baclofen) Orthopedic surgery Neurosurgery NEUROLYSIS • Phenol injections • Alcohol injections CHEMODENERVATION • Botulinum toxin ORAL MEDICATIONS • Baclofen • Dantrolene • Diazepam • Tizanidine NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR SPASTICITY PHYSICAL OR OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY SURGICAL OPTIONS • Stretching • Selective dorsal rhizotomy • Orthotics • Tendon Lengthening or transfers • Casting, splinting, positioning • Spinal cord stimulator • Thermal or electrical modalities • Biofeedback COMMONLY USED ORAL MEDICATIONS FOR SPASTICITY TREATMENT ORAL MEDICATION • • • • BACLOFEN DANTROLENE DIAZEPAM TIZANIDINE ADVANTAGES • Decreases frequency and severity of painful spasms • Improves ROM • DISADVANTAGES • Sedation, weakness, nausea, dizziness • Hallucinations due to sudden withdrawal • Drowsiness, diarrhea, malaise, weakness • Hepatotoxic • Weakness, sedation • Dependence with long use • Weakness, sedation, drowsiness, dry mouth, dizziness Decrease clonus, hyperreflexia, muscle stiffness and cramping • Reduces muscle tone • Reduces frequency of spasms • Reduces muscle spasms • Reduces spasticity without altering muscle power INTRATHECAL AGENTS: ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES MEDICATION Intrathecal baclofen (pump implantation) Other drugs (eg. Morphine) ADVANTAGES Direct administration of baclofen into spinal canal allows continuous supply of baclofen to site of action. Useful for severe or generalized cases of spasticity that do not respond to other less invasive treatments. Less CNS affects compared with oral baclofen because of the reduced dose required. DISADVANTAGES Surgical technique to implant reservoir and catheter to thecal sca. Risk of complications due to catheter or pump failure and infection. Drowsiness Headache Weakness Reduced painful spasms Risk of drug withdrawal Reduces muscle tone and frequency of spasms while increasing ROM High upfront cost COMMONLY USED NERVE AND MUSCLE INJECTABLE MEDICATIONS FOR SPASTICITY MANAGEMENT MEDICATION Alcohol Phenol ADVANTAGES Quick onset of action DISADVANTAGES Reduces tone, increased passive ROM Associated pain, skin irritation, muscle discomfort Reduces temporary nerve block lasting up to several months Highly variable duration of action, pain, muscle necrosis, dysesthesia Helps control muscle spasticity Botulinum toxin Causes localized decrease in symptoms Transient muscle weakness Reduces spasticity related pain Reversible Tolerance can develop NEUROLYTIC AGENTS: MECHANISM OF ACTION MEDICATION Alcohol, phenol MECHANISM OF ACTION Primary mechanism involves denaturing proteins and tissue destruction. Lower concentrations result in decreased conductance of potassium and sodium while high concentrations result in effects on proteins. Behaves as a local anesthetic Onset of actions < 1hr duration approximately 2-12 wks Provides focal neuromuscular blockade Complications include transient pain Perineural blocks can be used for proximal muscles or when multiple muscles need to be injected (risk of long lasting dysesthesia) CHEMODENERVATION AGENTS: MECHANISM OF ACTION MEDICATION Botulinum toxin MECHANISM OF ACTIONS Inhibition of acetylcholine in neuromuscular junction that leads to reduction in muscle activity. Onset of action, within 7 days; duration, approximately several months. Provides improvement in pain symptoms Can result in weakness in non-target muscles SURGICAL OPTIONS • May reduce spasticity for some patients • Combining orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery, with subsequent rehabilitation, helps normalize biomechanics of the spine and extremities and manage tone. • Selective dorsal rhizotomy, in combination with physiotherapy, has been shown to be safe and effective for reducing spasticity. BOTULINUM TOXIN SEROTYPES • Serotypes and preparations • A, B, C1, D, E, F, G • Differ in complex size and compositionexcipients, serotype manufacture processes and testing methods. • Dosing and pharmacology cannot be generalized across serotypes and brands/products. • Duration of effect will vary widely among serotypes. • Mechanism of actions will vary by serotype. BOTULINUM TOXIN TARGET PROTEINS ACTION/TARGET PROTEIN SEROTYPE • SELECTIVE CLEAVAGE OF SNAP-25 A, C1, E • Leads to inhibition of acetylcholine release • CLEAVAGE OF VAMP, OTHERWISE KNOWN AS SYNAPTOBREVIN • INHIBITION OF SUBSTANCE P, CGRP, AND GLUTAMATE RELEASE B, D, F, G A BOTULINUM TOXIN – MECHANISM OF ACTION BOTULINUM TOXIN: PROPERTIES AND ACTIONS • Focal intramuscular injection therapy • Physiologic action • Reversible • Titratable to the patient’s needs • Reduces muscle overactivity • Improves passive /active function • Facilitates ease of care • Increases comfort • Prevents or delays musculoskeletal complications • Lessens disfigurement PROPRIETARY BOTULINUM TOXINS AVAILABLE • Abobotulinumtoxin A Serotype A Dysport • Incobotulinumtoxin A Serotype A Xeomin • Onabotulinumtoxin A Serotype A Botox • Rimabotulinumtoxin B Serotype B Myobloc INDICATIONS FOR THE DIFFERENT BOTULINUM TOXINS Indication Dysport Blepherospasm and strabismus Cervical dystonia √ Glabellar lines √ Xeomin Botox √ √ √ √ Myobloc √ √ Axillary hyperhydrosis √ Upper limb spasticity √ Many of these have been tested for the other indications listed above with literature reports available BLACK BOX WARNING • The effects of all botulinum toxin treatments may spread from the injection site to other areas, causing symptoms similar to botulinum toxin effects. • Unexpected muscle weakness or loss of strength, hoarseness or trouble speaking, difficulty saying words clearly, loss of bladder control, double vision, blurred vision, drooping eyelids, and difficulty breathing or swallowing which can be life threatening. There have been deaths reported. • Symptoms reported hours to weeks after injection ONABOTULINUMTOXIN A - BOTOX • Serotype A • Indications and usage: • Cervical dystonia, primary axillary hyperhidrosis, blepherospasm, strabismus and chronic migraine. • Also approved for upper extremity spasticity in adults. • Decreases severity of increased muscle tome in elbow flexors (biceps). Wrist flexors (FCR and FCU), and finger flexors (FDP and FDS). • Important limitations • Safety and efficacy not established of other upper ext muscle groups or lower limb spasticity. • Not demonstrated to improve function or ROM when joint is affected by fixed contracture. • Does not replace usual standard of care rehabilitation therapies. DOSING CONSIDERATIONS • The Pharmacology of the botulinum toxin preparations cannot be compared to each other or exchanged. • Variability exists with toxin preparation, injection techniques, injection site, severity of spasticity and other confounding dosing issues which must be considered. • Awareness of the wide range of dosing schedules and understanding of how to incorporate this expertise into clinical setting are important to achieving optimal treatment results. • Duration of effect will vary with different preparations. • In addition, even the dose units of different serotype A toxins are not interchangeable and there are no dose conversion factors that are reliable. BOTULINUM TOXIN INJECTION TECHNIQUE • Generally, the dose is based on the size of the muscle and motor unit. • The smallest dose is generally used to start but may be based on the degree of spasticity. • Distribution of the injection dose • Smaller muscles may only require one injection site., usually mid-belly. • Larger or wider muscles may require injections in more than one site. • The needle is Teflon coated and will allow EMG to be performed or electrical stimulation in only a small number of motor units. • Both techniques can be used to localize. • Deeper muscles require longer needles. • Ultrasound guidance can be used to direct the needle into the muscle for added specificity and accuracy. • To evaluate for fixed contracture, a diagnostic nerve block can be performed with lidocaine or bupivacaine. INCREASING EFFECTIVENESS OF BOTULINUM TOXIN INJECTIONS • Target the motor end plate region. • Perform active and passive stretching of injected muscles (with or without electrical stimulation). • Nerve stimulation may boost botulinum toxin action. • Studied in Gastroc/Soleus/Tib posterior. • Botulinum toxin plus E-stim gave a better response to control group. • Felt to help target muscle fascicules with a high density of NMJ. • Increase the dilution of the toxin to allow greater spread. • Theoretical concerns include spread out of the injected muscle and systemically. EXAMPLE: TREATMENT OF ADDUCTED, INTERNALLY ROTATED SHOULDER WITH BOTULINUM TOXIN • Inject pectoralis major and minor • Palpate the muscles to minimize the risk of pneumothorax. • Distribute dose among several sites • Lat dorsi and teres major may cause shoulder adduction and are accessible below the post axillary fold. Increase accuracy with EMG, Ultrasound and or E-Stim. EXAMPLE: TREATMENT OF WRIST FLEXION WITH BOTULINUM TOXIN • Inject flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor carpi radialis. • May need to inject finger flexors too • FDS for proximal interphalangeal joint flexion. • FDP for distal interphalangeal joint flexion. • Inject 2 sites per muscle CONCLUSIONS • Spasticity is one type of “muscle overactivity.” Other visible components include spastic dystonia and spastic co-contraction. • These can be managed effectively with a combination of modalities, including but not limited to: PT/OT physical interventions, and medications given orally, intrathecally or directly into tissues in the form of neurolysis. • Injury to the CNS leads to muscle over activity which leads to immobilization, shortening of tissues, contracture, disuse and then poor function, hygiene and discomfort. • Management is dependent on the presentation but also on the desired effect and function and usually requires a comprehensive approach with good follow-up. • Both medication management and neurolytic injections have advantages and disadvantages and often are used in combination depending on the outcome desired. • More research is needed to define criteria for therapies, follow the effects of treatments in order to make definitive recommendations.