ID12

advertisement

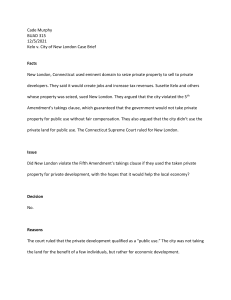

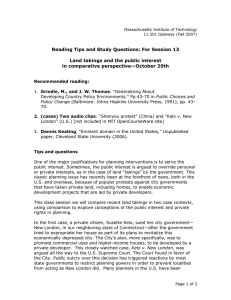

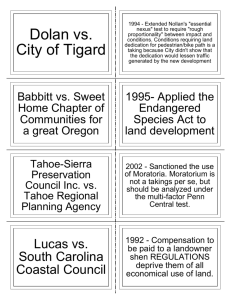

Case Brief – by Cassie Crosby Case: Kelo et al. v. City of New London et al. No. 04-108; Argued February 22, 2005; Decided June 23, 2005 Supreme Court of Connecticut Plaintiff: Kelo et al. – owners of properties earmarked for the New London integrated development plans, to revitalize its economy Defendant: City of New London et al. – Connecticut city attempting to buy up private property for a revitalizing development plan Facts of the Case: In 2000, New London approved an extensive development plan intended to revitalize the city’s failing economy, characterized by the closing of large companies, high unemployment, and decreasing population. The New London Development Corporation drew up growth plans, and pharmaceutical company Pfizer planned to construct a large research facility in the area. The state approved the plan and allowed the NLDC to purchase property using eminent domain of New London. The NLDC proceeded to purchase private property from voluntary sellers in the Fort Trumbull area, but encountered resistance from nine of the property owners. These homeowners rejected New London’s attempted use of eminent domain, saying it would here violate the Fifth Amendment’s “public use” clause. Procedural History: The plaintiffs proposed the Court create a new “bright line” rule redefining economic development as incomparable to public use, and that the Court should require “reasonable certainty” that public benefits from such takings will actually result. New London claimed this development plan was necessary to invigorate its economy. The trial court allowed a permanent restraining order for taking some of the properties, whereupon the case was presented to the Supreme Court of Connecticut. Court Opinion: The Connecticut Supreme Court affirmed in part and reversed in part, upholding all of the NLDC’s proposed takings. The city’s economic development was deemed “public use” as defined by the Fifth Amendment. The court found the careful plan was not created for an illegitimate or primarily-private purpose, and even though most of the property will not be directly open for the public, “the court long ago rejected any [such] literal requirement.” The question addressed was then whether the plan would serve a “public purpose.” The case Berman v. Parker served to show that an area that “‘must be planned as a whole’ to be successful” was reasonable justification for valid public use. The court resolves, as in Berman, to evaluate in light of the plan as a whole, rather than individual plaintiffs’ complaints. Similarly, the court used Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff to display that only the taking’s intention, and not its manner, are relevant for determining public use – transfer from private holder to private holder does not necessarily indicate public use will not result. Specifically addressing plaintiffs’ request for a new “bright line” rule, the court states that “economic development is a… long accepted function of government,” and is therefore public. The plaintiffs’ alternative request of instituting a new court rule for reasonable public use from takings is denied in light of Mikdiff, wherein “wisdom of takings… [is] not to be carried out in the federal courts.” Dissenting Opinion: The dissenting judges state that “economic development” serves as a banner that allows private takings for private, “upgraded” use. The judges parse the specific language of the Fifth Amendment, using “public use” and “just compensation” as limitations meant to protect property, a right denied through the majority opinion. Three types of public uses are described in this opinion, being: transfer of private property to public ownership; private property to private owner’s who make the land available to the public; and takings that serve a public purpose even if owned privately. The key issue asks when a “‘public purpose’ taking meets the public use requirement.” In using Berman and Midkiff again, these judges pose those cases as different from the one at hand – pre-condemnation use was harmful to the general public. They find issue with the majority opinion, saying that any ordinary private use could be skewed to show some public benefit. Finally, they state the precedence set is one of property rights being stripped and disproportionately wealthy people gaining influence over takings. Disposition of Case: The court affirmed in part and reversed in part the original trial court’s ruling, stating that the takings qualify as “public use” under the Fifth Amendment. Analysis: Course Topic: Takings (Conflicting Property Rights & The Law) How does the case relate? This case helped to define what qualified as “public use” under the Fifth Amendment, and therefore when eminent domain could be claimed for private property takings. The ruling here found that public purpose (i.e. the proposed economic reinvigoration of the Fort Trumbull area), in benefitting a larger general public, was sufficient for “public use,” without being directly and fully utilized by said public. “Public purpose” can be interpreted much more broadly than “public use,” and the court chose to defer to legislators when defining its specifics. Which previous cases are related? How do they differ? No previous cases seem related to Kelo as we have seen in class. This is the first one surrounding direct government involvement in private property rights, whereas other cases have been disputes between private parties over their respective, claimed property rights. How does the case affect economic incentives and efficiency? This case can be interpreted as promoting economic efficiency incentives. Governments, based on Kelo, recognize their option of reinvigorating the economy and realizing larger economic benefits through the use of eminent domain. Reevaluation of geographic areas that serve a small benefit or are even detrimental seems an immediate result of this decision. By granting governments more control with which to exert eminent domain, cities and states can create economically-efficient situations from areas that would otherwise serve as “wastes” of money or space – such as areas of extreme dilapidation or poverty, as in Berman. On the other hand, Kelo could serve to grant governments too broad a range of what “public purpose” could mean, opening the possibility of private-to-private transfers at the request of financially- or socially-connected citizens. As long as a general, larger public benefit would result from the takings, a more efficient use, then Kelo served its purpose of creating a more efficient economy. Whether or not it incentivizes extreme government action to create money-making areas that ignore general public welfare depends on legislators’ definition of “public purpose,” rather than “public use.”