Takings Law: Issues of Interest to Mineral Property Owners Chapter 10

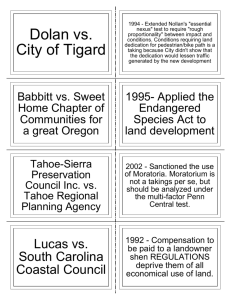

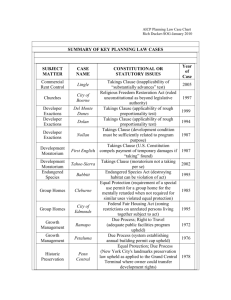

advertisement

Chapter 10 Cite as 21 Energy & Min. L. Inst. ch. 10 (2001) Takings Law: Issues of Interest to Mineral Property Owners Judith A. Villines Michele M. Whittington Stites & Harbison Frankfort, Kentucky Synopsis § 10.01. Introduction.................................................................................. 373 § 10.02. General Takings Principles ......................................................... 374 [1] — Development of “Physical” Takings Law........................... 375 [2] — Early Development of “Regulatory” Takings Law ............ 376 [3] — Development of “Confiscatory Regulatory” Takings......... 378 [4] — Recognition of “Per Se” or “Categorical Takings” ............ 379 § 10.03. Analytical Framework................................................................. 380 [1] — Determination of Property Rights....................................... 380 [2] — Determination of Taking ..................................................... 382 [3] — Determination of Just Compensation ................................. 383 [4] — Interest on Awards of Just Compensation........................... 386 § 10.04. Application of Takings Jurisprudence to Mineral Interests ..................................................................... 387 [1] — Statutory Prohibitions or Limitations on Mining ............... 387 [2] — Permitting Actions .............................................................. 391 § 10.05. Future Takings Cases? ................................................................ 394 [1] — Antiquities Act .................................................................... 394 [2] — Section 522 Designations of Lands Unsuitable for Mining ........................................................................... 395 § 10.06. Conclusion .................................................................................... 397 § 10.01. Introduction. The Fifth Amendment Takings Clause, while simple in its statement, has given rise to a complicated array of cases with varying rules that often appear inconsistent at best. This principle is particularly true in mineral cases. The most obvious examples of seemingly inconsistent mineral takings cases are the United States Supreme Court cases of Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon1and Keystone Bituminous Coal Ass’n v. 1 Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon, 260 U.S. 393 (1922). § 10.02 ENERGY & MINERAL LAW INSTITUTE DeBenedictis.2 Although both cases considered the effect of statutes3 that regulated mining in circumstances that might cause subsidence, in one case (Mahon) the Court found a taking, and in the other (Keystone) it did not. In this instance, as well as other seemingly inconsistent takings cases, the Court has found a basis for distinguishing the cases and applying separate rules despite the seeming similarity of the facts.4 Consequently, as one Justice noted, even the wisest lawyer has difficulty in discerning the principles of takings law that will be applied by the courts. This chapter attempts to provide an outline of the general principles of current takings law and a framework for analyzing a takings issue in the context of a mineral case. It also identifies the most recent cases that may have an effect on the analysis that will be used by courts in a mineral takings case. § 10.02. General Takings Principles. The body of law that has come to be known as “takings” law derives from the clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution which provides in pertinent part :” . . . nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” 5 This clause is commonly called the “Takings Clause” although some Justices and courts continue to refer to it as the “Just Compensation Clause.”6 The United States Supreme Court has embraced a general “fairness and justice” standard for the operation of the Clause, declaring that the Clause operates “to bar Government from forcing some people alone to bear public burdens which, in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole.”7 2 Keystone Bituminous Coal Ass’n v. DeBenedictis, 480 U.S. 470 (1987). 3 The Kohler Act was at issue in Mahon and the Subsidence Act was at issue in Keystone. 4 Justice Stevens explains in his dissent in Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council, 505 U.S. 1003 at 1072-1073 (1992) that “[u]nlike the Kohler Act, which simply transferred back to the surface owners certain rights that they had earlier sold to the coal companies, the Subsidence Act affected all surface owners — including the coal companies — equally.” 5 U.S. Const. amend. V. 6 Lucas, 505 U.S. at 1071 (Stevens, J. dissenting). 7 Armstrong v. United States, 364 U.S. 40, 49 (1960). 374