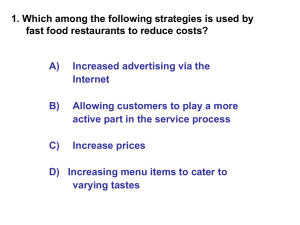

Operations Strategy - Deeltentamen 1

advertisement