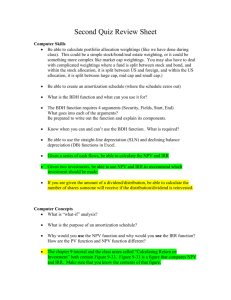

Capital Budgeting II: Cash Flow Estimation

advertisement

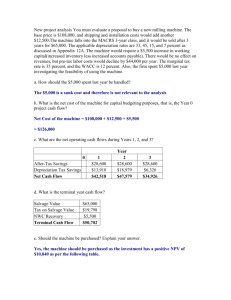

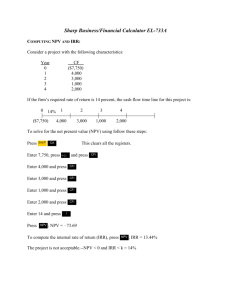

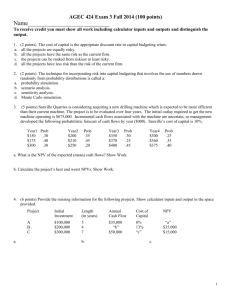

Ch 12 Cash Flow Estimation and Risk Analysis 1 Estimating cash flows NPV, IRR and PI computations are straightforward. The difficult part is estimating cash flows accurately occurring in the future. Estimating accurate cash flows for a large capital spending is critical. 2 Timing of project CFs 0 1 2 3 4 Initial Outlay OCF1 OCF2 OCF3 OCF4 NCF0 NCF1 + Terminal CF NCF2 NCF3 NCF4 3 Identifying the relevant cash flows Only cash flows are relevant, not accounting income. Costs of Fixed Assets Depreciation Changes in Net Working Capital Interest Expense Focus on incremental cash flows Incremental cost: cash flows that occur if and only if we accept the project (i.e., CF with project – CF without project). Example: Sunk cost, Opportunity cost, and erosion or externalities 4 Only cash flows are relevant. Only cash flows are relevant, not accounting income (or cost). The accounting income (or cost) ignores time value of money. Example: Consider the firm buying a building for $100,000 today. How much of $100,000 will be recorded as an accounting expense in the current year? Assume a straight-line depreciation over 20 years. What is the true capital expense in the current year? The entire $100,000 is an immediate cash outflow. Capital budgeting analysis focuses on cash inflows and outflows when they occur. 5 Noncash charge In calculating net income, accountants usually subtract depreciation from revenue. However, depreciation is noncash charge. You never write a check made out to “depreciation”. Depreciation must be added back when estimating a project’s cash flow. 6 Working Capital Expenditures Many capital investments require additions to working capital Net working capital (NWC) = current assets minus current liabilities Increase in NWC is a cash outflow; decrease a cash inflow • An example… We have to buy inventory to support sales although we haven’t collected cash yet Thus, usually, in the earlier years of the project life, increase in NWC is treated as cash outflow. However, recall that when the project winds down, we enjoy a return of net working capital. 7 Should CFs include interest expense? Dividends? NO. The costs of capital are already incorporated in the analysis since we use them in discounting. If we included them as cash flows, we would be double counting capital costs. 8 Forget sunk costs but include opportunity costs Forget sunk costs. Example: The Coca-Cola is launching a new brand in the beverage market. Previously, the company paid a consulting firm $300,000 to perform a test-marketing analysis. Is this expenditure relevant to the decision of introducing a new brand? NO! Include opportunity costs. Example: Lexmark Co. has an empty land that can be used to build a new factory. Alternatively, Lexmark could sell the land out. Currently, a real estate appraisal concludes that the current market price of the land is $1 million. If Lexmark decides to build new factory on that land, should Lexmark include $1 millions as a part of initial cash outlay? 9 YES! Include all incidental or side effects. Consider Erosion or externalities (e.g., product cannibalization). Example 1: Suppose the Innovative Motors Corporation (IMC) is determining the NPV of a new convertible sports car. Some of the customers who would purchase the new convertibles are owners of IMC’s compact sedan. Suppose the NPV of the sports car and the NPV of lost sales due to the transfer from sedan to convertible sports car is $100 million and -$150 million, respectively. What is the net NPV of a new convertible sports car project? Net NPV = $100 million - $150 million = -$50 million. REJECT! Example 2: Pepsi One case. 10 Consider after-tax cash flow. Pay tax (cash outflow) or receive tax credit (cash inflows) Taxes = (Market Value – Book Value ) * Tax Rate Example: Suppose you bought your Mustang for $15,000 five years ago. Today you decide to sell Mustang for $9,000 and buy new BMW for $30,000. Assume you depreciate your Mustang on a straightline basis over 10 years of life with a zero salvage value. What is the net cash flow? Assume the tax rate is 30%. 11 Consider after-tax cash flow. Annual Depreciation $15,000 / 10 = $1,500 Book value $7,500 ($15,000 – ($1,500* 5 years)) Market value $9,000 Gain from sale $1,500 Tax (30%) $450 ($1,500*30%) Net cash flow = - $30,000 + $9000 – $450 = -$21,450 12 Depreciation Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) Depreciable Basis Purchase Price + Shipping and Installation Costs Sale of a Depreciable Asset Taxes = (Market Value – Book Value ) * Tax Rate 13 Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) Year 3-year 5-year 7-year 10-year 1 33% 20% 14% 10% 2 45 32 25 18 3 15 19 17 14 4 7 12 13 12 5 11 9 9 6 6 9 7 7 9 7 8 4 7 9 7 10 6 11 3 100% 100% 100% 100% 14 Example: Campbell Co. The Campbell Company is evaluating the proposed acquisition of a new milling machine. The machine’s base price is $108,000, and it would cost another $12,500 to modify it for special use by your firm. The machine falls into the MACRS 3year class, and it would be sold after 3 years for $65,000. The machine would require an increase in net working capital (inventory) of $5,500. The milling machine would have no effect on revenues, but it is expected to save the firm $44,000 per year in before-tax operating costs, mainly labor. Campbell’s marginal tax rate is 35 percent. The project’s cost of capital is 12 percent. 15 Timing of project CFs 0 1 2 3 4 Initial Outlay OCF1 OCF2 OCF3 OCF4 NCF0 NCF1 + Terminal CF NCF2 NCF3 NCF4 16 Initial Cash Outlay at t=0 Purchase Price Modification Increase in NWC Initial Cash Outlay $108,000 $ 12,500 $ 5,500 $126,000 17 Operating Cash Flows Depreciation Depreciable Basis = Cost + Additional Cost = $108,000+ 12,500 = $120,500 Depreciation Schedule (MACRS 3-year class) Year 1 2 3 % 33% 45% 15% Basis Depreciation $120,500 $39,765 $120,500 $54,225 $120,500 $18,075 18 Let’s set up Income Statement to find Operating Cash Flows Net Revenue (or Gross Margin) - Depreciation = EBT Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 $44,000 $44,000 $44,000 ($39,765) ($54,225) ($18,075) $4,235 -$10,225 $25,925 ($1,482) ($3,579) ($9,074) = Net Income $2,753 -$6,646 $16,851 + Depreciation $39,765 $54,225 $18,075 = Net Operating Cash Flow $42,518 $47,579 $34,926 19 - Taxes (40%) Terminal Cash Flow Accumulated Depreciation (t=3) = Depreciation (t=1) + Depreciation (t=2) + Depreciation (t=3) = $39,765 + $54,225 + $18,075 = $ 112,065 Book Value = Depreciable basis - Accumulated Depreciation (t=3) = $120,500 – $112,065 = $8,435 Book value Market value Gain from sale Tax (35%) $ 8,435 $65,000 $56,565 $19,798 ($56,565*35%) 20 Terminal Cash Flows Proceeds form sale Tax on gain Recovery of NWC 65,000 -19,798 5,500 Terminal Cash Flow $50,702 21 Timing of project CFs: Campbell Co. 0 1 2 3 Initial Outlay 42,518 47,579 34,926 -126,000 42,518 + 50,702 47,579 85,628 NPV = $10,841 Accept! IRR = 16.37% > 12% (cost of capital) Accept! 22 Sensitivity and Scenario Analyses Why sensitivity and scenario analysis? In some cases, we may face forecasting risk or estimation risk. Forecasting risk – how sensitive is our NPV to changes in the cash flow estimates, the more sensitive, the greater the forecasting risk For example, we may miscalculate future cash flows. We also overestimate or underestimate the required return or cost of capital (Discussed in Ch 9) So we need to conduct “what-if” analysis to see how sensitive the NPV, IRR and others to varying input values. 23 Project Risk Analysis What does “risk” mean in capital budgeting? Uncertainty about a project’s future profitability. Measured by NPV, IRR, beta. 24 What three types of risk are relevant in capital budgeting? Stand-alone risk Corporate risk Market (or beta) risk 25 How is each type of risk measured, and how do they relate to one another? 1. Stand-Alone Risk: The project’s risk if it were the firm’s only asset and there were no shareholders. Ignores both firm and shareholder diversification. Measured by the of NPV, IRR, or MIRR. 26 Probability Density 0 E(NPV) NPV Flatter distribution, larger , larger stand-alone risk. 27 2. Corporate Risk: Reflects the project’s marginal effect on corporate earnings stability. Considers firm’s other assets (diversification within firm). Depends on: project’s , and its correlation with returns on firm’s other assets. Measured by the project’s corporate beta. 28 Profitability Project X Total Firm Rest of Firm 0 Years 1. Project X is negatively correlated to firm’s other assets. 2. If correlation < 1.0, some diversification benefits. 3. If correlation = 1.0, no diversification effects. 29 3. Market Risk: Reflects the project’s effect on a welldiversified stock portfolio. Takes account of stockholders’ other assets. Depends on project’s and correlation with the stock market. Measured by the project’s market beta. 30 How is each type of risk used? Stand-alone risk is easiest to measure, more intuitive. Core projects are highly correlated with other assets, so stand-alone risk generally reflects corporate risk. If the project is highly correlated with the economy, stand-alone risk also reflects market risk. 31 Measuring Stand-Alone Risk Three techniques Sensitivity Analysis Scenario Analysis Monte Carlo Simulation 32 What is sensitivity analysis? Shows how changes in a variable such as unit sales affect NPV or IRR. Each variable is fixed except one. Change this one variable to see the effect on NPV or IRR. Answers “what if” questions, e.g. “What if sales decline by 30%?” 33 Illustration Change from Base Level -30% -20 -10 0 +10 +20 +30 Resulting NPV (000s) Unit Sales Salvage WACC $ 10 35 58 82 105 129 153 $78 80 81 82 83 84 85 $105 97 89 82 74 67 61 34 NPV (000s) Unit Sales Salvage 82 k -30 -20 -10 Base 10 Value 20 30 35 Results of Sensitivity Analysis Steeper sensitivity lines show greater risk. Small changes result in large declines in NPV. Unit sales line is steeper than salvage value or WACC, so for this project, should worry most about accuracy of sales forecast. 36 Pros and Cons of Sensitivity Analysis Pros Gives some idea of stand-alone risk. Identifies dangerous variables. Gives some breakeven information. Cons Does not reflect diversification. Says nothing about the likelihood of change in a variable, i.e. a steep sales line is not a problem if sales won’t fall. Ignores relationships among variables. 37 What is scenario analysis? Examines several possible situations, usually worst case, most likely case, and best case. Provides a probability, likelihood of each case occurrence 38 Assume we know with certainty all variables except unit sales, which could range from 900 to 1,600. Scenario Probability NPV(000) Worst Base 0.25 0.50 Best 0.25 $ 15 82 148 E(NPV) = $ 82 (NPV) = 47 39 Are there any problems with scenario analysis? Only considers a few possible out-comes. Assumes that inputs are perfectly correlated--all “bad” values occur together and all “good” values occur together. Focuses on stand-alone risk, although subjective adjustments can be made. 40 What is a simulation analysis? A computerized version of scenario analysis which uses continuous probability distributions. Computer selects values for each variable based on given probability distributions. NPV and IRR are calculated. Process is repeated many times (1,000 or more). End result: Probability distribution of NPV and IRR based on sample of simulated values. Computer-intensive 41 Probability Density xxxx xxxxxxx xx xxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx 0 E(NPV) NPV 42 Pros and Cons of Simulation Analysis Reflects the probability distributions of each input. Shows range of NPVs, the expected NPV and NPV. Difficult to specify probability distributions and correlations. If inputs are bad, output will be bad: “Garbage in, garbage out.” 43 Sensitivity, scenario, and simulation analyses do not provide a decision rule. They do not indicate whether a project’s expected return is sufficient to compensate for its risk. Sensitivity, scenario, and simulation analyses all ignore diversification. Thus they measure only stand-alone risk, which may not be the most relevant risk in capital budgeting. 44