Mercer Writing Program Fall Faculty Development Workshop

advertisement

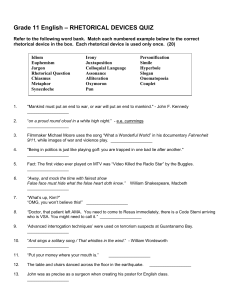

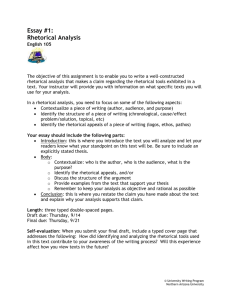

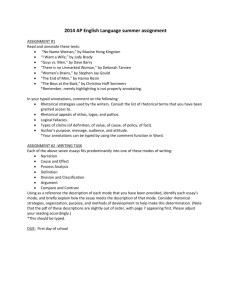

Mercer Writing Program Faculty Development Workshop Wednesday, 12 August 2015 The Long Room of The Old Library, Trinity College Dublin “I would remind the faculty and the administration of what each knows: that the work they do takes second place to nothing, nothing at all, and that theirs is a first order profession.” ~Toni Morrison, Wellesley Commencement Address, 2004 Agenda I. Write Now: 2015-16 in the Writing Program *What’s New on the Writing Program Website: Newsletter, Preceptor Services, Calendar *The College Writing Pre-Game Show & Preceptor Modeling Techniques *Faculty Research and Writing Colloquium *Directed Reading: Adler-Kassner and Wardle’s Naming What We Know II. What’s Past Is Prologue: Updates from the May 2015 Workshop *Five Paper “Problem” … Four Paper “Process” *Revised Framework of Expectations for Writing Instruction Courses *Scaffolding Writing Instruction into the Syllabus & the ‘Iceberg’ Approach *Paradigms of Instruction and Interaction III. The Name of Action: Implementing Scaffolded Writing Instruction *Cycling Writing Instruction *A Threshold Concept’s Compositional ‘Footprint’ *Modeling a “Day in the Life” of a Writing Instruction Course using Rhetoric and They Say/I Say IV. Thanne longen folke to go on pilgrimmage: Breakout Sessions in Knight *Profile Pics: Seeing Ourselves as Writing Instructors *Think Globally; Act Locally: The Framework for your Course & Implementation in Context *(Re)Gather Ye Rosebuds: Reconvene for Sharing Results, Questions, & Concerns I. Write Now: Mercer Writing Program 2015 –16 Drop-in-Day Tutorials Skill Sets Sessions Lunch & Listen: Preceptor Training Open Classes Mercer Writing Program Faculty-Preceptor Tea Faculty Research & Writing Colloquium The College Writing Pre-Game Show I Fall to Pieces: Parts with a Purpose in the Academic Essay (Word)Play Stations; or, The Syntax Repair Shop If you Build It, They Can Read: Grammar Gaming Style Matters: Formatting & Documentation Parts with a Purpose Highlights Questions of “What” – What Am I trying to Prove? Thesis Statements: A thesis is a powerful instrument when envisioned and executed correctly. Remember that it is defined by the OED as, “a proposition designed to influence the mind.” Questions of HOW --- How Am I going to Prove it? Make sure that your thesis is an ASSERTION rather than merely an observation. It should be a clearly stated claim that can be proved or demonstrated through the presentation of evidence. Body Paragraphs: The body paragraphs represent your opportunity to make good on the promise of credibility and validity made by your thesis & the Introduction. Introductions: An essay’s Introduction is the rhetorical equivalent of “making a first impression.” It provides you, as the writer, an opportunity to “set the scene or stage,” influencing the reader’s attitude towards the topic and your argument BEFORE the presentation of the evidence begins. This means creating a context, vividly described and engagingly presented, from which your reader will begin to evaluate and respond to your ideas. The Introduction also represents your chance to establish ethos, or “credibility” as an author. Here you demonstrate your case and give the reader grounds for belief by presenting concrete, specific evidence drawn from appropriate primary and secondary sources. The organization of the body paragraphs (the order and arrangement of your ideas and evidence as they are presented to the reader) also provide an opportunity to “influence the reader’s mind.” By presenting specific details in purposely chosen order, you can lead the reader to think, feel, and/or do certain things(!) at certain points in your argument. (Word)Play Stations: This Pre-Game Activity gets students thinking about what makes a good sentence. You might start by identifying effective sentences in touchstone texts in the course readings or sample student papers. You can also have students create a class archive of strong sentences and effective paragraphs they encounter in their reading throughout the semester. Periodically, I have students share some of these and discuss their individual merits. The (Word)Play exercises ask them to put this attention to sentence quality in action by revising ineffective or clichéd sentences. The exercises in your packet focus on improving descriptive sentences, but they could easily be adapted to other modes of writing, depending on the genre of a given formal paper in your syllabus. Of course, improving students’ descriptive sentence writing is always time well-spent given its important role in composing summary, analysis, or reflective essays. Grammar Gaming : Scavenger Hunt: This Pre-Game Activity allows students to review grammatical conventions together in a competitive atmosphere that can be fun as well as informative. Students are divided into teams and given a sheet with a series of grammatical issues that crop up frequently. The object of the game is to use The Little Bear (or if you prefer, Purdue’s OWL site) to identify where that topic is explained and then to copy some of that information into the worksheet and correct sample sentences. Teams compete to see who can complete the sheet first. They then put their results up on the board and compare their solutions to the sheet’s various grammatical problems. Working with a Preceptor (or Using their Techniques if you don’t have one): Extracts from Spring 2015 Lunch & Listen Handouts In WRT 490 and 491, we discuss practice strategies for what I call a “modeling unit” of writing instruction. A modeling unit uses course readings that will not be the focus of a formal writing assignment to introduce students to critical reading, note-taking, and pre-writing strategies. It then gives them a chance to practice those approaches in a low risk setting by producing a plan for a collaborative “practice paper” in class. A preceptor can play a crucial role in such an in-class activity not only by making contributions to the discussion but, more importantly, by modeling at the board the kinds of strategies that are being introduced. In doing so, the preceptor engages in what scholars of rhetoric and composition describe as “directive” tutoring: showing students HOW in a step by step fashion to take the raw materials of their ideas and shape them into the kind of pre-writing components that lead to a stronger paper. The Lunch & Listen demonstrations in last Spring’s training courses presented practical strategies for an inclass writing instruction activities that could be used in a range of writing instruction classes at Mercer, from INT/GBK 101 to a WRT 120/GBK 202 and INT 201 or GBK 203. Even if you don’t have a preceptor in your course, you can use these strategies with your students, either by leading the modeling at the board yourself, or by letting individual students take turns doing so during discussion. The topics for the Spring were: “Effective Annotation: How to take Reading & Discussion Notes that Facilitate Writing” in WRT 490 and “Making a Claim: From Brainstorming Ideas to the Working Thesis Statement” in WRT 491. In addition to addressing these topics, this Fall’s Lunch & Listen sessions will be keyed to specific chapters in Birkenstein and Graff’s They Say/I Say. “Effective Annotation: How to take Reading & Discussion Notes that Facilitate Writing” in WRT 490 Reading Assignment for the Demonstration: “What’s Lost as Handwriting Fades,” by Maria Konnikova, The New York Times, June 2, 2014 Reading Assignment on Annotation and Note-Taking Strategies: “Active Critical Reading: Prereading and Close Reading,” from Writing in the Disciplines: A Reader and Rhetoric for Academic Writers.” 7th Edition. Mary Lynch Kennedy and William J. Kennedy, Pearson, Boston: 2012. *Please note: I have included some excerpts from this text, used in our Lunch & Listen session below. Complete handouts are available for download on the Writing Program website: http://departments.mercer.edu/english/writing/ PREREADING QUESTIONS: *What does the title indicate the text will be about? *How do the subtitles and headings function? Do they reveal the organizational format (for example, introduction, body, conclusion)? *Is there biographical information about the author? What does it tell me about the text? *Are there other salient features of the text, such as enumeration, italics, boldface print, indention, diagrams, visual aids, or footnotes? What do these features reveal about the text? *Does the text end with a summary? What does the summary reveal about the text? STRATEGIES FOR ELABORATING ON TEXTS EXPAND THE TEXT *Agree or disagree with a statement in the text, giving reasons for your agreements or disagreement. *Compare or contrast your reactions to the topic (for example, “At first I thought . . . but now I think . . .). *Extend one of the points. Think of an example and see how far you can take it. *Discover an idea implied by the text but not stated. *Provide additional details by fleshing out a point in the text. *Illustrate the text with an example, an incident, a scenario, or an anecdote *Embellish the text with a vivid image, a metaphor, or an example. *Draw comparisons between the text and books, articles, films, or other media. *Validate one of the points with an example. *Make a judgment about the relevance of one of the statements in the text. *Impose a condition on a statement in the text. (For example, “If . . . then . . . “) QUESTION THE TEXT *Draw attention to what the text has neglected to say about the topic. From “Active Critical Reading”: “Critical reading is accompanied by various types of *Test one of the claims. Ask whether the claim really holds up. writing: freewriting and brainstorming, taking notes, posing and answering questions, *Assess one of the points in light of your own prior knowledge of the topic or with your own or others’ experience. *Question one of the points. *Criticize a point in the text. Take a single paragraph and question every claim in it. responding from personal experience, paraphrasing, summarizing, and quoting. Readers need a place to record all this writing. We suggest that you use a writer’s notebook . . . You will fill your writer’s notebook with informal writing, some of which will emerge in *Assess the usefulness and applicability of an idea. the formal writing you do at a later date. . . . A writer’s notebook is not an end in itself. The entries are recorded with an eye toward later writing. They may become the basis for an essay, provide evidence for an argument, or serve as repositories of apt quotations. Consider your writer’s notebook as a record of your conversations with texts, as well as a storehouse for collecting material you can draw on when writing” (5-6). Preceptors and Modeling: the Collaborative “Practice Paper” ~Preceptors stand at the board and model effective note-taking strategies, showing students how to identify those ideas in discussion that should be written down as potential raw material for formal papers. ~Preceptors may then work with the professor to lead students as a group through each stage of the pre-writing process in order to develop a collaborative “practice paper.” that responds to a specific prompt. This modeling activity may be done in a single class or spread out across two or three meetings as a means of preparing students to write their own individual essays. ~It may be more manageable to divide the class into “focus groups” that explore particular aspects of a text, such as content or structure, with the preceptor leading one group and the faculty member another. Then have the groups reconvene and integrate their results in the plans for the collaborative paper. ~Once students have been taken through the pre-writing stages relevant to the prompt and the discipline, they may be broken up into new focus groups that work on particular parts of the collaborative paper, from the working thesis to plans for body paragraphs and appropriate evidence. ~Students who have engaged in this kind of collaborative activity could then apply the same strategies in their individual papers and would be prepared to work one on one with the preceptor either in an in-class workshop, during a Drop In Day session, or in an individual tutorial outside of class. II. What’s Past Is Prologue: Program Updates Revisiting the Five Paper “Problem” The original language of the Guidelines for Writing Instruction Courses calls for requiring at least five formal papers, totaling 20-25 pages, in line with best practices in the field. In our writing instruction courses, that practice has been complicated by the numerous additional student learning outcomes the classes are expected to deliver. Dubbed the Five Paper “Problem,” many faculty have expressed concerns with having to rush through formal writing assignments without sufficient time for students to be instructed in and practice one genre before moving on to the next one. In the Spring 2015 semester, the Writing Committee revisited this issue in order to consider its impact on writing pedagogy and student learning. As a result, the Committee voted to revise this parameter of the Guidelines from requiring five papers to four, in hopes of optimizing writing instruction and student learning outcomes. Framework for Expectations in Writing Instruction Courses (Revised Spring 2015) Framework for Expectations in Writing Instruction Courses (Revised Spring 2015) At the May 2015 Workshop, we took the ideas of scaffolding assignments and backward design and applied them to the structuring of a syllabus in order to integrate writing instruction more fully with the content of the class. Using threshold concepts from the revised Framework for Expectations for Writing Instruction Courses, we considered the question of what students would need to know and do before attempting a given formal paper. Answers to that question helped define where we might introduce or reinforce particular threshold concepts and when we should have students practice them. This strategy gives targeted writing instruction a discernible ‘footprint’ in the class meetings leading up to the writing of the rough draft, which increases the chances of student success in completing that assignment. A copy of the May Workshop packet with complete instructions for this syllabus-building strategy is available for download on the Writing Program website. Scaffolding Writing Instruction into the Syllabus The ‘Iceberg’ Approach: Margaret Symington’s ‘Planning’ vs. ‘Student” Syllabi Original Schedule from Senasi’s F14 INT 101 Syllabus: 11/11: Calvino, Cosmicomics “The Distance of the Moon” (3-16) 11/13: Kosslyn, “How the Brain Creates Personality: A New Theory” (Bb) 11/14: Calvino, Cosmicomics “The Dinosaurs” (97-112) 11/18: Calvino, “The Dinosaurs” continued (97-112) and Gould, “Darwin’s Delay” (Bb) 11/21: Calvino, Cosmicomics “The Aquatic Uncle” (71-82) 11/25: Calvino, Cosmicomics “Without Colors” (3-16); Ovid, “Orpheus and Eurydice” (Book X Metamorphoses) Out-of-Class Pre-Writing Assignment, Paper 4 11/27 & 28: Thanksgiving Break 12/2: Calvino, Cosmicomics “Without Colors” continued; Science Daily, “Color Perception is Not In The Eye of the Beholder: It’s In the Brain” (Bb) 12/4: Kelves, “The New Enlightenment” (Bb) 12/5: Pre-Writing and Thesis Workshop for Paper 4; PAPER 4 DUE ON BLACKBOARD ON SUNDAY, 7 DECEMBER BY MIDNIGHT Part of the Same Section ‘Iceberged’ as a Planning Syllabus 11/11: Calvino, Cosmicomics “The Distance of the Moon” (3-16); CLOSE READING OF PAPER GUIDELINES: a) IDENTIFY KEY WORDS AND SPECIFIC CHALLENGES; b) CHOOSE ONE OF TWO OPTIONS FOR THE PAPER’S AUDIENCE: SENASI’S NEXT INT 101 CLASS, OR VISITORS TO MERCER’S WEBSITE INTERESTED IN THE INTEGRATIVE LEARNING PROGRAM 11/13: Kosslyn, “How the Brain Creates Personality: A New Theory” (Bb); [AUDIENCE ANALYSIS] IN-CLASS INFORMAL WRITING – COMPARE/CONTRAST KOSSLYN’S AUDIENCE WITH CALVINO’S AND IDENTIFY SPECIFIC PLACES WHERE THE NEEDS/EXPECTATIONS OF THE AUDIENCE ARE TAKEN INTO ACCOUNT 11/14: Calvino, Cosmicomics “The Dinosaurs” (97-112) 11/18: Calvino, “The Dinosaurs” continued (97-112) and Gould, “Darwin’s Delay” (Bb) 11/21: Calvino, Cosmicomics “The Aquatic Uncle” (71-82); [LOGIC, CLARITY, COHERENCE] COLLABORATIVE REVERSE OUTLINE OF THE STORY, IDENTIFYING WHICH CHARACTER(S) REPRESENT THE “SELF” AND WHICH REPRESENT THE “OTHER” 11/25: Calvino, Cosmicomics “Without Colors” (3-16); Ovid, “Orpheus and Eurydice” (Book X Metamorphoses) Out-of-Class Pre-Writing Assignment, Paper 4 11/27 & 28: Thanksgiving Break Writing Instruction Paradigms: Classical Rhetoric – Focus on the writer’s text and its formal dimensions (Product) Expressivist – Focus on writing as self-discovery, language as mode of self-expression (Process) Social Constructionist – Focus on socio-cultural/historical settings in which writers develop understanding of language and knowledge (Context, Discourse Communities) Defining our Interactions with Students and their Writing: Minimalist – Emphasizes students’ agency; relies on open-ended questions/topics to generate students’ critical thinking and self-directed exploration of topics Directive –Employs modeling to demonstrate concrete strategies and approaches to particular kinds of questions and/or writing tasks. May be especially helpful for novice or challenged writers. Directed Readings; or, What Your Writing Director’s Reading Now Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, University Press of Colorado, 2015 Threshold Concepts – “those deemed central to a particular subject; concepts necessary for knowledge transfer; the portal to the opening of academic literacy” From the preview I gave of the book at our May Workshop: The soon-to-be-released Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies (June 2015, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle) “examines the core principles of knowledge in the discipline of writing studies using the lens of ‘threshold concepts’—concepts that are critical for epistemological participation in a discipline. The first part of the book defines and describes thirty-seven threshold concepts of the discipline in entries written by some of the field’s most active researchers and teachers, all of whom participated in a collaborative wiki discussion guided by the editors.” “Many people assume that all writing abilities can be learned once and for always. However, although writing is learned, all writers always have more to learn about writing. The ability to write is not an innate trait humans are born possessing. Humans are ‘symbol-using (symbol-making, symbol misusing) animals,’ and writing is symbolic action, as Kenneth Burke has explained (Burke 1966, 16). Yet learning to write requires conscious effort, and most writers working to improve their effectiveness find explicit instruction in writing to be more helpful than simple trial and error without the benefit of an attentive reader’s response. Often, one of the first lessons writers learn, one that may be either frustrating or inspiring, is that they will never have learned all that can be known about writing and will never be able to demonstrate all they do know about writing.” ~Shirley Rose, “All Writers Have More to Learn,” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, 2015 Let’s Take a Break and Have Snacks! III. The Name of Action: Implementing Scaffolded Writing Instruction Cycling Threshold Concept Instruction MODELING: GAMING: TS/IS Templates ‘Touchstone’ Texts Rhetorical/Structural/Genre Analysis of Readings Sample Student Papers Targeted Annotation Practice and Checks Incorporate – Use in Formal Writing Do Again – Recursive Practice (Word)Play Stations Picture This: Composing Visual Arguments Pin the Emoticon on the Paragraph Word Lottery Name & Demonstrate Do – Student Practice Reflect & Assess COLLABORATING REFLECTING Collaborative Reports/Papers In-Class Practice Papers and Paragraphing Crowdsourced Research – Creating a Class Database Creating a Class Archive Reverse Outlining Targeted Peer Editing Hear Yourself Think Listening Exercise Talking Points Memo and Presentation NAME: AUDIENCE: Demonstrate through relationships in Rhetorical Situation: the Writer/Speaker, the Audience/Reader, and the Context/Conditions of Composition. Touchstone Text: “Letter from Birmingham Jail” INCORPORATE: Use materials developed in this cycled instruction on audience in a formal assignment written to a defined audience that calls for analysis of rhetorical effectiveness in the “Letter” Name & Demonstrate Incorporate – Use in Formal Writing REVISE: Revise collaborative paragraphs to include details from reflection, integrating analysis of the use of appeals with the rhetorical situation Do Again – Recursive Practice Do – Student Practice DO: TARGETED ANNOTATION & COLLABORATIVE PARAGRPHING: Identify & annotate elements of rhetorical situation in the “Letter.” Compose a draft paragraph explaining the text’s rhetorical situation. Reflect & Assess REFLECT: COLLABORATIVE REVERSE OUTLINE : Identify where “The Letter” uses Aristotle’s rhetorical appeals. Reflect as a group on why/how those particular appeals might be appropriate to Dr. King’s rhetorical situation There and Back Again: A Threshold Concept’s Compositional ‘Footprint’ Rhetorical • Situation AUDIENCE * Relationship to Writer/Speaker * Context: Author’s Exigence * Conditions of Production and/or Consumption Genre Language *Formal Conventions *Defining Appropriate Evidence *Domains & Discourse Communities *Assumptions about Familiarity with Key Concepts *Paragraph & Sentence structures *Tone *Allusions *Individual Word Choices *Specialized Lexicons/Technical Terms “Writing is both relational and responsive, always in some way part of an ongoing conversation with others.” ~Andrea Lunsford, “Writing Addresses, Invokes, And/Or Creates Audiences,” Naming What We Know, 21 Modeling A Day in the Life of a Writing Instruction Course Description of Writing Assignments in the Student Syllabus: Formal Writing Assignments: There will be four formal writing assignments in the course, each of which will be developed in stages – from pre-writing, to outlining, drafting, peer editing, and revision; this approach to academic writing is called “scaffolding.” Paper 1: Rhetorical Analysis – the Foundational Questions Essay. This analytic essay introduces students to two foundational questions that are central to the course: a) What is the argument being made about a given topic? b) How is that argument being made? Using rhetorical analysis, the essay will respond to these questions by exploring perceptions of self and others as they are represented in Martin Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Specifically, your essay will make a claim about how rhetorical appeals are used in “The Letter” to respond to the audience’s perception of “self” and “other” in Dr. King’s rhetorical situation. A Few Rhetorical Terms: Rhetorical Appeals: From Aristotle’s Ars Rhetorica, delineate the major forms of appeal speakers or writers employ in working to persuade an audience. Logos – appeal to logic, reason, factual information Ethos – appeal to credibility of the speaker/writer, or shared cultural values Pathos – appeal to strong feelings, emotion Exigence: That which compels someone to speak; circumstances, events that motivate speech/writing Kairos: Term from classical rhetoric for the opportune occasion for speech; “the way a given context for communication both calls for and constrains one's speech” through contingencies of place, time, and culture. Rhetorical Situation: Modern term with some similarity to kairos; composed of the Speaker/Writer, the Listener/Reader, and the Context – the circumstances that condition the production and consumption of the speech or text Rhetorical Triangle: Composed of the Speaker/Writer, the Listener/Reader, and the Message Selected Material from Readings in They Say/I Say for this unit of the Course: Chapter 3: “As He Himself Puts It: The Art of Quoting” “A key premise of this book is that to launch an effective argument you need to write the arguments of others into your text. One of the best ways to do so is by not only summarizing what “they say,” as suggested in Chapter 2, but by quoting their exact words . . . But the main problem with quoting arises when writers assume that quotations speak for themselves . . . In a way, quotations are orphans: words that have been taken from their original contexts and that need to be integrated into their new textual surroundings.” (42-43) Strategies & Templates: Quote Relevant Passages – Before you can select appropriate quotations, you need to have a sense of what you want to do with them . . . sometimes quotations that were initially relevant to your argument, or to a key point in it, become less so as your text changes during the process of writing and revising (43-44). Frame Every Quotation – Since quotations do not speak for themselves, you need to build a frame around them in which you do that speaking for them (44). Templates for Introducing &Explaining Quotations – The one piece of advice about quoting our students say they find helpful is to get in the habit of following every major quotation by explaining what it means (47) . most Chapter 4: “Yes/No/Okay, But” “Although each way of responding is open to endless variation, we focus on these three because readers come to any text needing to learn fairly quickly where the writer stands, and they do this by placing the writer on a mental map consisting of a few familiar options “ (56). Strategies: Disagree & Explain Why – You need to do more than simply assert that you disagree with a particular view; you also have to offer persuasive reasons why you disagree (58). Agree but with a Difference – Just as you need to avoid simply contradicting views you disagree with, you also need to do more than simply echo views you agree with (61). Agree and Disagree Simultaneously – The parallel structure – “yes and no”; “on the one hand I agree, on the other I disagree” – enables readers to place your argument on that map of positions . . . while still keeping your argument sufficiently complex (64-65). Chapter 8: “As A Result” “This chapter addresses the issue of how to connect all the parts of your writing. The best compositions establish a sense of momentum and direction by making explicit connections among their different parts, so that what is said in one sentence (or paragraph) both sets up what is to come and is clearly informed by what has already been said. When you write a sentence, you create an expectation in the reader’s mind that the next sentence will in some way echo and extend it, even if – especially if – that next sentence takes your argument in a new direction” (107). Strategies: Using transition terms (like “therefore” and “as a result”) – For readers to follow your train of thought, you need not only to connect your sentences and paragraphs to each other, but also to mark the kind of connection you are making. One of the easiest ways to make this move is to use transitions (from the Latin root trans, “across”), which help you cross from one point to another in your text (108-109). Adding pointing words (like “this” or “such”) -- Such terms help you create the flow . . . that enables readers to move effortlessly through text. In a sense, these terms are like an invisible hand reaching out of your sentence, grabbing what’s needed in the previous sentences and pulling it along” (113). Developing a set of key terms and phrases for each text you write – Develop a constellation of key terms and phrases, including their synonyms and antonyms, that you repeat throughout your text. When used effectively, your key terms should be items that readers could extract from your text in order to get a solid sense of your topic (114). Repeating yourself, but with a difference – To effectively connect the parts of your argument and keep it moving forward, be careful not to leap from one idea to a different or introduce new ideas cold. Instead, try to build bridges between your ideas by echoing what you’ve just said while simultaneously moving your text into new territory (116). I: Introduction to the Domains – Thumbnail Sketches of Self and Others 8/18- Introduction to the Course: Aristotle’s Rhetorical Appeals: Logos, Ethos, and Pathos; Defining Critical Thinking; Close Reading and Annotation Strategies 8/20- Ovid, “Narcissus and Echo” (Bb) and Rossetti’s “In an Artist’s Studio” They Say/I Say, Introduction (1-14); Also view Escher’s Self Portrait with Sphere and PreRaphaelite portraits posted in Gallery on Blackboard(Bb) 8/24: They Say/I Say, Chapter 1 (19-29) Elliott, “Self, Society, and Everyday Life” (Bb) 8/25: They Say/I Say, Chapter 2 (30-40) Kosslyn, “What Shape Are A German Shepherd’s Ears?” (Bb) 8/27: Foster-Wallace, “This Is Water” (Bb) In-Class Writing Assignment 1: Summary and Paragraphing 8/31: King, “Letter From Birmingham Jail” (Bb) They Say/I Say, Chapter 3 (42-50) 9/1: King, “Letter From Birmingham Jail” continued They Say/I Say, Chapter 4 (55-67) Begin Pre-Writing Assignment, Paper 1 9/3: Osborn, “Rhetorical Distance in Letter from Birmingham Jail” (Bb) They Say/I Say, Chapter 7 (92-100) 9/8: College Writing “Pre-Game Show” – Bring your They Say/ I Say text, your Little Bear Handbook, your copy of “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” and your Pre-Writing assignment 9/10: Peer Editing Workshop Paper 1 – Bring a typed hard copy of your Revised Rough Draft, your Little Bear Handbook, and a colored pen. 9/14: They Say/I Say, Chapter 8 (105-118) FINAL DRAFT PAPER 1 DUE ON BB BY MIDNIGHT Implementation in Context: Suggestions for Planning A Day in the Life of a Writing Instruction Course 1. Locate a place in the schedule where a writing instruction component is scaffolded in, or where you’d like to place one as preparation for a formal writing assignment. 2. Identify threshold concept(s) from the Framework, rhetorical terms, strategies from TS/IS and/or other compositional topics that seem especially relevant to that assignment. Decide on strategies (modeling, TS/IS templates, collaborative paragraphing or practice paper, gaming, etc. ) for introducing or revisiting those components. 3. Consider the relation of “what” to “how.” Here we might ask ourselves how a particular reading, whose content we value and want to impact our students, may derive its power not just from what it says but how it says it. Have students examine the reading as a composition, identifying the ‘footprint’ of threshold concepts such as purpose, audience, or clarity, both as a model for their own writing and as an avenue to a deeper understanding of the text. 4. Map these activities onto the planning syllabus, paying particular attention to any opportunities to connect those elements of writing instruction with the overarching theme of the course, such as “Self and Other,” “Gods and Heroes,” or “Building Community.” 5. Prepare a kind of “Talking Points” memo or notes (as formal or informal as you like) detailing instructions for activities and illustrative points to facilitate the discussion and practice of writing in the class. Such memos can also be posted on Blackboard or another CMS to serve as a resource for students as they prepare their rough drafts of the formal paper. I: Introduction to the Domains – Thumbnail Sketches of Self and Others 8/18- Introduction to the Course: Aristotle’s Rhetorical Appeals: Logos, Ethos, and Pathos; Defining Critical Thinking; Close Reading and Annotation Strategies 8/20- Ovid, “Narcissus and Echo” (Bb) and Rossetti’s “In an Artist’s Studio” They Say/I Say, Introduction (1-14); Also view Escher’s Self Portrait with Sphere and PreRaphaelite portraits posted in Gallery on Blackboard(Bb) 8/24: They Say/I Say, Chapter 1 (19-29) Elliott, “Self, Society, and Everyday Life” (Bb) 8/25: They Say/I Say, Chapter 2 (30-40) Kosslyn, “What Shape Are A German Shepherd’s Ears?” (Bb) 8/27: Foster-Wallace, “This Is Water” (Bb) In-Class Writing Assignment 1: Summary and Paragraphing 8/31 -- Audience: Move 8/31: King, “Letter From Birmingham Jail” (Bb) They Say/I Say, Chapter 3 (42-50) From DFW’s embodied audience to King’s as central to his exigence. 9/1: King, “Letter From Birmingham Jail” continued They Say/I Say, Chapter 4 (55-67) Begin Pre-Writing Assignment, Paper 1 8/31 -- Genre of letter and its relationship to audience; King’s explicit incorporation of audience as shaping both content & structure. 9/1 – Review Rhetorical Appeals; Targeted Group Annotation to identify instances of Logos, Ethos, Pathos; Reflect on appeals’ relation to Rhetorical Situation. 9/3: Osborn, “Rhetorical Distance in Letter from Birmingham Jail” (Bb) They Say/I Say, Chapter 7 (92-100) 9/3 – Use Osborn to model TS/IS 9/8: College Writing “Pre-Game Show” – Bring your They Say/ I Say text, your Little Bear strategies : writing others’ voices in, Handbook, your copy of “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” and your Pre-Writing assignment responding, connecting parts , repetition with a difference. 9/10: Peer Editing Workshop Paper 1 – Bring a typed hard copy of your Revised Rough Draft, your Little Bear Handbook, and a colored pen. 9/14: They Say/I Say, Chapter 8 (105-118) FINAL DRAFT PAPER 1 DUE ON BB BY MIDNIGHT Audience: Move From DFW’s embodied audience to King’s as Martin Luther King, Jr. Birmingham City Jail April 16, 1963 Bishop C.C.J. Carpenter central to his exigence. Bishop Joseph A. Durick Rabbi Milton L. Grafman Bishop Nolan B. Harmon The Rev. Nolan B. Harmon The Rev. Edward V. Rammage Genre of letter and its relationship to The Rev. Earl Stallings audience; King’s explicit incorporation of My Dear Fellow Clergymen: audience as shaping both content & structure. Discuss how “Letter’s” opening illustrates exigence & the rhetorical concept of audience. While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling my present activities "unwise and untimely." Seldom do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If I sought to answer all the criticisms that cross my desk, my secretaries would have little time for anything other than such correspondence in the course of the day, and I would have no time for constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of genuine good will and that your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I want to try to answer your statement in what I hope will be patient and reasonable terms. Ask students to identify use of appeals here; discuss how ethos & audience connect here. Genre of letter and its relationship to audience; King’s explicit incorporation of audience as shaping both content & structure. Have Workshop Groups discuss how passage illustrates some of TS/IS emphasis on writing as response. We have waited for more than 340 years for our constitutional and God given rights. The nations of Asia and Africa are moving with jetlike speed toward gaining political independence, but we still creep at horse and buggy pace toward gaining a cup of coffee at a lunch counter. Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, "Wait." But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six year old daughter why she can't go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five year old son who is asking: "Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?“ Review Rhetorical Appeals; Targeted Group Annotation to identify instances of Logos, Ethos, Pathos; Reflect on appeals’ relation to Rhetorical Situation. In your statement you assert that our actions, even though peaceful, must be condemned because they precipitate violence. But is this a logical assertion? Isn't this like condemning a robbed man because his possession of money precipitated the evil act of robbery? Isn't this like condemning Socrates because his unswerving commitment to truth and his philosophical inquiries precipitated the act by the misguided populace in which they made him drink hemlock? Isn't this like condemning Jesus because his unique God consciousness and never ceasing devotion to God's will precipitated the evil act of crucifixion? We must come to see that, as the federal courts have consistently affirmed, it is wrong to urge an individual to cease his efforts to gain his basic constitutional rights because the quest may precipitate violence. Society must protect the robbed and punish the robber. TS/IS: Writing others’ into the text,, Connecting the parts, pointing to earlier introduction of the key concept/phrase “rhetorical distance.” Use Osborn to model TS/IS strategies : writing others’ voices in, responding, connecting parts , repetition with a difference. “Rhetorical distance” may seem a novel concept, but as usual there is really little new under the rhetorical sun. Aristotle had already written of magnification and minification, the strategic enlargement or suppression of character and events. Francis Bacon described the rhetorical function as the convergence of reason and the imagination, in effect telescoping time and distance to achieve “the better moving of the will.” And Kenneth Burke featured the concepts of identification and division, a striking but somewhat limited, two-valued expression of the importance of controlling and manipulating the distance between speaker and audience, audience and adversaries, policies and practices. Nevertheless, rhetorical distance may be one of those fresh ways of conceiving and expressing these phenomena of symbolic space, a novel lens that can reveal new detail. Michael Osborne is Professor Emeritus of Communication at the University of Memphis in Memphis, Tennessee. Michael Osborn, “Rhetorical Distance in ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail,’ Rhetoric & Public Affairs, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2004, pp. 23-36. Discuss strategies for identifying appropriate, relevant sources. Thanne longen folke to go on pilgrimmage : Breakout Sessions in Knight *Profile Pics: Seeing Ourselves as Writing Instructors Using the paradigms and approaches shared earlier, consider what your own “profile” as a writing instructor might look like. Does your approach tend towards a focus on product (Rhetoric), process (Expressivist), context (Social Constructionist) or a combination of all three? Would you characterize your interactions with students and their writing as more minimalist or directive? Discuss your ‘profile” with others in your group and consider how such pedagogical choices might relate to the specific spirit or content of your course, as well as its writing instruction components. *Think Globally; Act Locally: The Framework for your Course/Implementation in Context As a group take a closer look at and discuss the specifics of your course’s revised Framework. Which of these elements are already a part of your class and which ones might need to be more explicitly incorporated into your plans? The instructions in your packet (page 12) will guide you through one strategy for implementing elements of writing instruction into the plans for a given day’s class meeting. You may wish to go through them as a group with the sample syllabus, or work in pairs to consider how they may be used on your own draft syllabus. *(Re)Gather Ye Rosebuds: Reconvene for Sharing Results, Questions, & Concerns Great Books KNIGHT 108 INT 201 KNIGHT 100 R-Designated Courses WRT Knight 104 INT 101 KNIGHT 101