Constitutional Law II The Constitution limits government action that

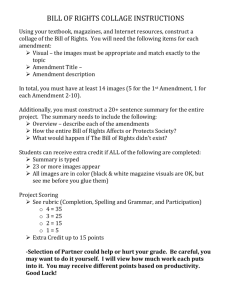

advertisement