Integrating Accessibility into the Design of Online Learning

advertisement

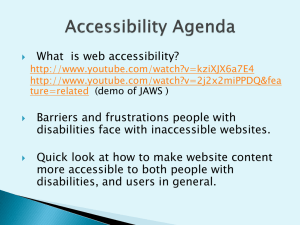

INTEGRATING ACCESSIBILITY INTO THE DESIGN OF ONLINE LEARNING MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS: THEORIES AND PRACTICE Nantanoot Suwannawut School of Library & Information Science Indiana University, Bloomington 14th Annual Accessing Higher Ground November 16, 2011 Overview of the Presentation Introduction of the study Accessibility and accessible e-learning Design of online systems and learning applications for persons with visual impairment Methodologies for the design of accessible systems Introduction of the Study • Purpose: To reviews the various theories, approaches, techniques, and technologies that are developed to ensure the information access for people with visual impairment, esp. in the design of online learning systems. • Goal: To explore the literature and ways that best serve the design of accessible systems for this group of learners. • Scope: To investigate appropriate models in order to integrate services and enhance efficiency of the learning system., excluding the depth exploration of technical issues. Accessibility and accessible e-learning • Definition of accessibility and associated terminologies o I. What is accessibility? o II. Accessibility and usability o III. accessibility and web accessibility • Perspectives, principles, and models of accessibility o I. Human and legal rights to information accessibility o II. Accessibility guidelines, standards, and policies o III. Alternate approaches to accessibility • Accessible e-learning. o I. Definition and background o II. Four accessibility models in e-learning Definition of Accessibility • “A process that aims to promote social inclusion by helping people from disadvantaged groups or areas access jobs and essential services" (Lincolnshire County Council, 2010). • There are two approaches to accessibility: direct and indirect access (Hackett & Parmanto, 2005). • Accessibility focuses on making things usable by people with disabilities, including temporary disabilities • Designing for functional limitations overlaps with designing for situational limitations. Accessibility and Usability • Usability is “extent to which a product can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals effectively, efficiently and with satisfaction in a specified context of use” (ISO 9241). • Specified users = people who have disabilities, whereas specified context = a wide range of situations including the use of assistive technologies. • People with disabilities encounter all the same problems that people without disabilities do (Shneiderman, 2000). • Most accessibility issues overlap with usability issues. Perspectives, Principles, and Models of accessibility • Accessibility is a matter of rights: human rights and legal rights. • There are a number of accessibility guidelines, standards, and policies (e.g. part III of the U.K. Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) 1995, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 Title 3, the 1998 amendment to the Rehabilitation Act, the ISO 9241171, etc.) • Among these accessibility guidelines, policies, and legislations, websites and their components are one of the most commonly mentioned (e.g. Section 1194.22 of the U.S. Section 508 on Web-based intranet and Internet information and applications, the Canadian Standard on the Accessibility, Interoperability and Usability of Web Sites, etc.) The Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) • A working group under the Worldwide Web Consortium (W3C) • Established in 1999 and is sponsored by a variety of government and industry supporters of accessibility. • Follows the theory of universal web accessibility one website fits or is designed for all users. • Three core principles of WAI: (a) authoring tools and development environments for producing an accessible interface and content of the web; (b) browsers, multimedia players and assistive technologies for providing a completely usable and accessible experience); and (c) accessible content (Chisholm & Henry, 2005) → Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines (ATAG), and User Agent Accessibility Guidelines (UUAG). Web content accessibility guidelines (WCAG) • Currently, there are two versions of the guidelines: the WCAG 1.0 (1999) and WCAG 2.0 (2008). • A specific checkpoint for each guideline performs as one method of accessibility assessment with criteria for success • Numerous scholars and researchers continue to comment on these documents, e.g. ambiguity, complexity, and validity. Alternate Approaches to Accessibility I. The engineering approach (Brajnik, 2005) o Views accessibility as a process, rather than a target, and to explicitly define appropriate corporate policies, corporate guidelines and corporate implementation plans to be used accordingly. o Defines accessibility policy together with clear goals and missions, specifying the level of accessibility needed to be achieved, and identifying the categories of users that should benefit most from the implementation of the policy. II. Accessibility organization (Urban and Burks, 2006) o View thes enterprise as some sort of organization that will handle and support accessibility issues and ensure enforcement. o Coordinates all of the organization resources and to bring various groups together to discuss accessibility and discover, define, and articulate issues related to accessibility of concern to both the whole enterprise and to its individual parts. Alternate Approaches to Accessibility (cont.) III. The holistic view (Sloan et al., 2006) o Adopts the inclusive view and promote the concept of usercentered design through personalization. o No single universal solution can appropriately address the needs of all of user groups. Instead, the developer can select relevant guidelines in order to implement a solution which is fit to the context of use or usable to the target audience, and that would take into account any access requirements such as user characteristics and technical requirements. Accessible E-learning • Accessible e-learning refers to design qualities that endeavor to make online learning available to anyone irrespective of their disability, and to ensure that the way it is implemented does not create unnecessary barriers to him/her interacting with a computer or connecting device (Cooper, 2006). • Each individual uses different AT, browsing techniques, navigation strategies, and so on. • Common barriers are lack of alternative text or keyboard support, frames without titles, absolute fontsize, poor color contrast, etc. • There is still broad evidence of the inaccessibility of e-learning experiences (Parry, 2010) The web accessibility integration model (Lazar, Dudley-Sponaugle, & Greenidge, 2004) • Adopts an approach of web accessibility An accessible • • • • website must be sufficiently flexible to be used by assistive technologies. Tries to assess whether online curriculum content and delivery software applications conform to the principles of standard/legislative compliance or meet accessibility requirements prescribed in the guidelines. Relies on advancing technology, i.e. accessible web sites, to solve e-learning problems and enhance learning for students with disabilities. Require skills to interpret and translate these principles and their implications for the learning technology community Compliance with the accessibility and de facto global e-learning standards cannot guarantee a satisfactory experience for learners with disabilities. The Composite Practice Model (Leung, Owens, Lamb, Smith, Shaw, & Hauff, 1999) • Focuses on linking experts and utilizing their knowledge in • • • • order to support students (= view people who use or are relevant to technologies as important as the technology itself) Believes in “best practice” and that the ultimate responsibility lies with the governing body of the institution. The AT service providers adopt the framework of the “actornetwork theory” (ANT) and a service delivery model. The model can be regarded as lacking in universality because of the wide scope of inspection for each agent. The constant technological change and the many contextual variables make it impractical to endorse a single model for service delivery. The Holistic Model (Kelly, Phipps, & Howell, 2005) • Places learners at the center of the development process and focus on the context in which accessible e-learnings developed. • Provides resources which are tailored for the students’ particular needs, and welcomes diversity. • Can leave out the perspectives of stakeholders other than students and perhaps lecturers. • Can become tiresome for a student to have to continually discuss his/her disability with various members of staff as they go through their degree program in order for their needs to be met. The Contextualized Model of Accessible E-Learning Practice in Higher Education (Seale, 2006) • Views the development of accessible e-learning as a practice or activity that can and will be mediated. • Three components: (1) all the stakeholders of accessibility within a higher education institution; (2) the context in which these stakeholders have to operate: drivers and mediators; and (3) how the relationship between the stakeholders and the context influences the responses they make and the accessible e-learning practices that develop. • Two theoretical frameworks for practicing: communities of practice and activity theory • In order to establish a strong tie of community, it takes time to build a strong network. Summary of Accessibility Approaches in the E-Learning Context Web accessibility integration model Composite practice model Holistic model Contextualized model Focus Web accessibility Accessibility organization Holistic view Engineering and corporate approach Philosophies Technological determinism Universal Design Stakeholders Contextualism Socio-culturalism Actor-Network theory Learner-centered theory Community of Practice, Activity theory Theories Methodological Conformance to approaches accessibility standards and guidelines Strengths Legislative compliance, general applicability Weaknesses Lack of subjectivity, lack of skills in interpreting standards Best practice, Active learner's Service delivery involvement with institutional engagement Integrity of Feasibility, governing responsive to bodies individual needs Mediation of constituents Lack of universality Organizational management Lack of cooperation, specificity clear division of responsibilities, systematic corpus of practice Design of Online Systems and Learning Applications for Persons with Disabilities • Accessibility and interaction design • Conceptual frameworks for design and accessibility • Conceptual framework and considerations for design of accessible online learning systems Accessibility and Interaction Design • Text-based interface -- GUI -- 3D internet or virtual worlds • Non-visual interaction (auditory and soma esthetic senses) • Most tools and software are essentially text-based interfaces which return information in the form of voice synthesis or Braille while offering keyboard control. • Normally there are four strategies for screen reader users to navigate and find web information: (1) Navigate through the headings on the page; (2) Use the "Find" feature; (3) Navigate through the links of the page; and (4) Read through the page. • Misunderstanding or losing track of the content is one of the most frequent problems encountered by screen reader users. Universal Design (UD) “Design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design" (Center for Universal Design, 2008). • A relatively new paradigm that emerged from "barrier-free" or "accessible design” • Seven core principles addressing the key concepts of universal design: Equitable Use, Flexibility in Use, Simple and Intuitive Design, Perceptible Information, Tolerance for Error, Low Physical Effort, and Size and Space Appropriate for Approach and Use. Conceptual Framework and Considerations for Design of Accessible Online Learning Systems "A framework for designing educational environments that enable all learners to gain knowledge, skills, and enthusiasm for learning" (Center of Applied Special Technology, 2007). • Creates flexible learning goals, instructions, materials, and assessment that accommodate needs of learners with the use of new technologies. • Three main principles: provision of multiple, flexible methods of presentation, methods of expression, and options for engagement. • Instructional and pedagogical practices should also be applied in the design framework. Recommendations for the Design of LMS • Provide learning contents in a variety of formats and can be • • • • • rendered in different platforms. This may include lowtechnology learning aids such as tactile charts and diagrams. Offer choices of assignments in various formats and styles. Provide additional links to supporting materials, and they should be opened in a different window. Allow extra time on synchronous and asynchronous communications, assignments and exams. Provide recording feature for synchronous communication for further revision. Offer personalized features, e.g. calendar, evaluation and assessment. Recommendations for the Design of LMS (cont.) • Offer consistency in layout and a structured page organization • • • • • with simple navigation. Ensure that using colors is not the only visual means to convey information or distinguish a visual element, e.g. comments, feedbacks, of sharing materials. Provide the summary of information on tables or visual presentation for repetition and reinforcement. Provide Directional and warning cues, e.g. a pop-up window with audio signals. Allow for correction/editing with hints to correct an error. Integrate accessibility features such as captioning, speed control, volume adjustment, font sizing, and color contrast. Recommendations for the Design of LMS (cont.) • Provide information about the accessibility of the system and • • • • course syllabus. Provide help tools or Tutorials for prerequisite knowledge. Provide links to support services, e.g. DSS office, library, and IT department. Integrate a tool to check browser capabilities. Provide a variety of languages and translation tool. Methodologies for the Evaluation of Accessible Systems • Guideline-based or standards review (automated tools & human/manual check) • Heuristic evaluation • Cognitive walkthroughs • Usability testing Guideline-based or Standards Review (automated tools & human/manual check) • The method to assess if a product or system conforms to specified • • • • • recommendations and/or standards for interface design. Accessibility standards reviews are often more rigorous than typical user interface reviews, particularly when conformance to a standard is a legal requirement (Henry and Grossnickle, 2004). Can be conducted manually by evaluators or through automated tools. The automated tools require a small time commitment. Some prescriptive guidelines are found to be voluminous, vague, conflicting, or divorced from the context in which sites are being developed (Ivory & Megraw, 2005). There are issues of subjective checkpoints, so the manual check is also recommended. Heuristic Evaluation • The method in which one or more reviewers check whether each design element conforms to a list of design or usability principles and take notes where the product does not follow those principles. • Majority of problems found through this heuristic method are rather specific and low-priority, and individual evaluators can identify a relatively small number of overall usability issues (Robin et al, 1991). • During the review, evaluators are allowed to consider any additional usability principles or results that come to mind that may be relevant for any specific dialogue element. • Provides a holistic perspective, not restricted only to the accessibility standards or guidelines conformance. Cognitive Walkthroughs • The method based on cognitive theory; it is a formalized way of imagining people's thoughts and actions when they use an interface for the first time without training (Lewis & Rieman, 1993). • Four elements are required: the task description, description of who the users will be and what relevant knowledge they possess, description or a prototype of the interface, and the complete correct action sequence (Lewis & Rieman, 1993). • A fully functioning prototype is not necessary for evaluation. • The method is time-consuming, and claimed to detect far more problems than actually exist and potential problems could be overlooked due to a narrow focus of the technique (Digital Accessibility Team, 2009). Usability Testing • Usability testing (or user testing) is a usability evaluation method that provides quantitative and qualitative data from actual users performing real tasks with a product. • The method usually involves three major components: potential users, representative tasks with a prototype, and systematic observation under controlled conditions. • Standard protocols for usability testing can be used with users with disabilities, but with few modifications (Henry & Grossnickle, 2004). • Other detailed considerations in conducting usability testing with users with disabilities such as determining Participant Characteristics and choosing the test location. References Brajnik, G. (2005a). Engineering accessibility through corporate policies. Retrieved January 18, 2010, from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.78.7362&rep=rep1&type=pdf Center for Universal Design, NCSU. (2008). Homepage. Retrieved 28 May, 2009, from http://www.design.ncsu.edu/cud/ Center of Applied Special Technology [CAST.] (2007). Universal Design for Learning. Retrieved 30 April, 2010, from http://www.advocacyinstitute.org/UDL/ Cooper, M. (2006). Making online learning accessible to disabled students: an institutional case study. ALT-J, Research in Learning Technology, 14(1), 103-115. Digital Accessibility Team. (2009). Cognitive walkthrough. Retrieved May 20, 2011, from http://www.tiresias.org/tools/cognitive_walkthrough.htm Henry, S. L., & Grossnickle, M. (2004). Just ask: Accessibility in the user-centered design process. Georgia Tech Research Corporation. Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Retrieved from http://www.uiaccess.com/accessucd/ International Organization for Standardization (ISO). (n.d.). ISO 9241-171:2008: Ergonomics of humansystem interaction Part 171: Guidance on software accessibility. Retrieved May 12, 2010, from http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_ics/catalogue_detail_ics.htm?csnumber=39080 References (cont.) Ivory, M. Y., & Megraw, R. (2005). Evolution of web site design patterns. ACM Transactions on Information Systems (TOIS), 23(4), 463-497. Kelly, B., Phipps, L., & Howell, C. (2005), Implementing a holistic approach to e-learning accessibility. In C. Cook & D. Whitelock (Eds.), Exploring the Frontiers of E-learning: Borders, Outposts and Migration, ALT-C 2005 12th International Conference Research Proceedings, ALT, Oxford. Retrieved from http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/web-focus/papers/alt-c-2005/ Lazar, J., Dudley-Sponaugle, A., & Greenidge, K-D. (2004). Improving web accessibility: A study of webmaster perceptions. Computers in Human Behavior, 20, 269-288. Lewis, C., & Rieman, J. (1993). Task-centered user interface design: A practical introduction. Retrieved January 3, 2010, from http://hcibib.org/tcuid/index.html#notice Lincolnshire County Council. (2010). Definition of accessibility. Retrieved February 2, 2011, from http://www.lincolnshire.gov.uk/residents/environment-andplanning/environment/accessibility/definition-of-accessibility/56334.article Leung, P., Owens, J., Lamb, G., Smith, K., Shaw, J. & Hauff, R. (1999). Assistive education. Retrieved October 29, 2008, from http://www.dest.gov.au/archive/highered/eippubs/eip99-6/eip99_6.pdf Parry, M. (2010). Colleges lock out blind students online, Chronicle of higher education. Retrieved December 14, 2010, from http://chronicle.com/article/BlindStudents-DemandAccess/125695/?sid=pm&utm_source=pm&utm_medium=en References (cont.) Petty, R.E. (2010). Technology access in the workplace and higher education for persons with visual impairments: An examination of barriers and discussion of solutions. Independent Living Research Utilization at TIRR. Houston, Texas. Retrieved March 29, 2010, from www.bcm.edu/ilru/html/.../Technology_Access_Visual_Impairments.DOC Robin, J., James, R. M., Cathleen, W., & Kathy, U. (1991). User interface evaluation in the real world: a comparison of four techniques, Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems: Reaching through Technology. New Orleans, Louisiana, United States: ACM. 119-124. Doi: 10.1145/108844.108862 Seale, J. (2006). The rainbow bridge metaphor as a tool for developing accessible e-learning practices in higher education. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 32(2). Retrieved from http://www.cjlt.ca/index.php/cjlt/article/viewArticle/56/53 Shneiderman, B. (2000). Universal usability. Communications of the ACM, 43(5), 85- 91. Sloan, D., Dickinson, A., McIlroy, N., & Gibson, L. (2006). Evaluating the usability of online accessibility information. Retrieved November, 8, 2010, from http://www.computing.dundee.ac.uk/staff/dsloan/usableaccessibilityadvice.htm Urban, M., & Burks, M. R. (2006). Implementing accessibility in the enterprise. In J. Thatcher, M. Burks, C. Heilmann, S. Henry, A. Kirkpatrick, P. Lauke, et al., Web accessibility (pp. 69-83). Apress. Thank you for your attention! Any comments and feedbacks are welcome: nansuwan@indiana.edu