Aggregate Demand, International Trade

advertisement

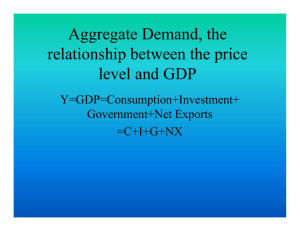

Aggregate Demand, International Trade and Exchange Rates Revised Oct 17, 2006 • We know from macro that a country's net exports, (X -IM), are one component of its aggregate demand, C + I + G + (X -IM). • Thus, an autonomous increase in exports or decrease in imports has a multiplier effect on the economy, just like an increase in C, I, or G. • This conclusion is shown on an aggregate demand and supply diagram. A rise in net exports shifts the aggregate demand curve outward to the right, changing the equilibrium from point A to point B. Both GDP and the price level rise. Price Aggregate Demand and Supply Diagram S1 Level A P1 D1 Q1 Real GDP Price Aggregate Demand and Supply Diagram S1 Level B P2 P1 A D2 D1 Q1 Q2 Real GDP What increases net exports? • a rise in foreign incomes Booms or recessions in one country tend to be transmitted to other countries through international trade in goods and services. • the relative prices of foreign and domestic goods law of demand. If the prices of the goods of Country X rise, people everywhere will tend to buy fewer of them--and more of the goods of Country Y. • A fall in the relative prices of a country's exports tends to increase that country's net exports and hence to raise its real GDP. • A rise in the relative prices of a country's exports will decrease that country's net exports and GDP. Relative Prices, Exports, and Imports • Assume -- just for this short section -- that exchange rates are fixed. • What happens if the prices of American goods fall while, say, Japanese prices are constant? • With U.S. products now less expensive relative to Japanese products, both Japanese and American consumers will buy more American goods and fewer Japanese goods. • As a result, America's exports will rise and its imports will fall, adding to aggregate demand in the U.S. • A rise in American prices (relative to Japanese prices) will decrease U.S. net exports and aggregate demand. Thus: • A fall in the relative prices of a country's exports tends to increase that country's net exports and hence to raise its real GDP. • A rise in the relative prices of a country's exports will decrease that country's net exports and GDP. The Effects of Changes in Exchange Rates • How do changes in exchange rates affect a country's net exports since currency appreciations or depreciations change international relative prices? (Remember: the basic role of an exchange rate is to convert one country’s prices into another country’s currency.) Exchange Rates and Home Currency Prices 30,000 Yen TV Set $1,000 US Home PC Price in The US Price in The US Price in Japan $1 = 120 30,000 Y $250 yen $/Y=.0083 $1,000 120,000 Y $1 = 100 30,000 Y $300 yen $/Y=.01 $1,000 100,000 Y Exchange Price in Rate Japan • From the American consumer’s viewpoint, a television set that costs 30,000 yen in Japan goes up in price from $250 (that is, 30,000/120) to $300 (that is, 30,000/100). • To Americans, it is just as if Japanese manufacturers had raised TV prices by 20 percent. • The Dollar price of the yen went from $0.0083 to $0.01 – an appreciation of the yen. • What about the implications for Japanese consumers interested in buying American personal computers that cost $1,000? • When the dollar falls from 120 yen to 100 yen, they see the price of these computers falling from 120,000 yen to 100,000 yen. • To them it is just as if American producers had offered a 16.7 percent drop in the price of PCs. • A currency depreciation should raise net exports and increase aggregate demand. • A currency appreciation should reduce net exports and therefore decrease aggregate demand. • In this case the U.S. dollar has depreciated. Thus, U.S. exports should rise. Depreciation P AS1 B A P1 AD2 AD1 Q1 GDP Appreciation P AS1 A P1 AD1 AD2 Q1 GDP Conclusions to date: currency depreciations increase AD. currency appreciations decrease AD. Aggregate Supply in an Open Economy • To complete the model of macroeconomics in an open economy, let’s look at the implications of international trade for aggregate supply. • The United States, like all economies, buys some of its productive inputs from abroad. • When the dollar depreciates, the prices of imported inputs rise. • The U.S. aggregate supply curve therefore shifts inward, pushing up the prices of U.S. made goods and services. • Conversely, an appreciation of the currency makes imports cheaper and shifts the U.S. aggregate supply curve outward thus pushing prices down. Depreciation P AS2 AS1 GDP Appreciation P AS1 AS2 GDP Macro economic effects of exchange rates • Let’s put aggregate demand and aggregate supply together and work through the macroeconomic effects of changes in exchange rates. • Suppose the international value of the dollar falls (i.e. it depreciates). • What happens to AD? • What happens to AS? A currency depreciation is inflationary and probably also expansionary. • When the dollar falls, foreign goods become more expensive to Americans. That effect is directly inflationary. AS shifts leftward. • At the same time, aggregate demand in the U.S. is stimulated by rising net exports. AD shifts to the right. • As long as the expansion of demand outweighs the adverse shift of the aggregate supply curve brought on by currency depreciation, real GDP should rise. Depreciation P AS2 AS1 P2 A P1 AD2 AD1 Q1 Q2 GDP • Qualification: Countries that borrow in foreign currency will see their debts increase whenever their currencies fall in value. • For example, an Indonesian business that borrowed $1,000 in July 1997, when $1 was worth 2,500 rupiah, thought it owed 2.5 million rupiah. • But when the dollar suddenly became worth 10,000 rupiah, the company owed 10 million rupiah. Many businesses found themselves unable to cope with their crushing debt burdens and simply went bankrupt. • Reverse direction. What happens when the currency appreciates. • In this case, net exports fall so the aggregate demand curve shifts to the left. At the same time, imported, inputs become cheaper, so the aggregate supply curve shifts outward. • Both of these shifts are shown in the Figure. Once again, as the diagram shows, we can be sure of the movement of the price level: It falls. • Output also falls if the demand shift is larger than the supply shift, as is likely. Thus: Appreciation P AS1 AS2 A P1 P2 AD1 AD2 Q2 Q1 GDP • A currency appreciation is disinflationary and probably also contractionary. • This analysis explains why many economists and financial experts cringe whenever the Japanese yen appreciates. • If Japan is already experiencing both deflation and recession. The last thing they need, economists argue, is a decrease in aggregate demand and further deflation. To date, we have analyzed international trade in goods and services, but have ignored international movements of capital. • For some nations, this omission is inconsequential because they rarely receive or lend international capital. • But things are quite different for the United States because the vast majority of international financial flows involve buying or selling assets whose values are stated in U.S. dollars. • In addition, we cannot hope to understand the origins of the various international financial crises without incorporating capital flows into the analysis. • Recall that interest rate differentials and capital flows are important determinants of exchange rate movements. • Suppose interest rates in the United States rise while foreign interest rates remain unchanged. • We have learned that this change in relative interest rates will attract capital to the U.S. and cause the dollar to appreciate. • We just showed that an appreciating dollar will, in turn, reduce net exports, prices, and output in the United States Thus: • A rise in interest rates tends to contract the economy by appreciating the currency and reducing net exports. • You learned in macro principles when you studied monetary policy that higher interest rates tend to reduce investment spending and hence reduce the I component of C + I + G + (X- IM). • In an open economy with international capital flows, we showed that higher interest rates also reduce the X - IM component. • Conclusion: International capital flows strengthen the negative effects of interest rate rises on aggregate demand. If interest rates fall in the United States, or rise abroad, everything we have just said is turned in the opposite direction. The conclusion is: • A decline in interest rates tends to expand the economy by depreciating the currency and raising net exports. Fiscal and Monetary Policies in an Open Economy We need to remember what we have learned in the discussion up to this point. Specifically: • A rise in the domestic interest rates leads to capital inflows and makes the exchange rate appreciate. A currency appreciation reduces aggregate demand and raises aggregate supply. • A fall in domestic interest rates leads to capital outflows and causes an exchange rate depreciation. A currency depreciation raises aggregate demand and reduces aggregate supply. Fiscal Policy Revisited Suppose the U.S. government cuts taxes or raises spending. P Closed Economy: Government Cuts Taxes or Raises G S0 B P2 A P1 D1 D0 Q1 Q2 GDP • Aggregate demand increases, which pushes up both real GDP and the price level in the usual manner. • This effect is shown as the shift from Do to the D1 in the figure. In a closed economy, that single shift is the end of the story. • But in an open economy with international capital flows, we must add in the macroeconomic effects that work through the exchange rate. • We do this by answering two questions. 1. What will happen to the exchange rate? • Fiscal expansion pushes up interest rates. • At higher interest rates, U.S. securities become more attractive to foreign investors, who go to the foreign exchange markets to buy dollars with which to purchase the securities. • This buying pressure drives up the value of the dollar. Thus: A fiscal expansion normally makes the exchange rate appreciate. 2. What are the effects of a higher dollar? • We know that when the dollar rises in value, U.S. goods become more expensive abroad and foreign goods become cheaper here in the U.S. • So exports fall and imports rise, driving down the X - IM component of aggregate demand. • The fiscal expansion thus winds up increasing America's capital account surplus (by attracting foreign capital) and its current account deficit (by reducing net exports). • In fact, the two must rise by equal amounts because, under floating exchange rates, it is always true that: Current account surplus + Capital account surplus = 0 Note: the induced rise in the dollar will shift the aggregate supply curve outward. the aggregate demand curve inward. The final equilibrium in an open economy is point C, whereas in a closed economy it would be point B. By comparing points B and C, we can see how international linkages change the picture of fiscal policy associated with a closed economy. P Open Economy-Government Cuts Taxes or Raises G S0 B S2 A P1 C D1 D2 D0 Q1 Real GDP Two main differences arise. • First, a higher exchange rate makes imports cheaper and thereby offsets part of the inflationary effect of a fiscal expansion. • Second, a higher exchange rate reduces the expansionary effect on real GDP by reducing X- IM. • In a closed economy we learned that an increase in G will crowd out some private investment spending by raising interest rates. • In an open economy, an increase in G, by raising both interest rates and the exchange rate, crowds out net exports. • But the effect is the same: The fiscal multiplier is reduced. Thus, we conclude that: International capital flows reduce the power of fiscal policy. Monetary Policy Revisited (i.e. in an open economy) • consider a tightening, rather than a loosening, of monetary policy. • contractionary monetary policy reduces aggregate demand, which lowers both real GDP and prices. (shift from Do to D1, and it looks like the exact opposite of a fiscal expansion. Without international capital flows, that would be the end of the story. ) P Contractionary Monetary Policy without International Capital Flows S0 A P0 P1 B D0 D1 Q1 Q0 Real GDP • But in the presence of internationally mobile capital, we need to work through the impacts on interest rates and exchange rates. • As we know from Ec152, a monetary contraction raises interest rates just like a fiscal expansion. • Hence, tighter money attracts foreign capital into the United States in search of higher rates of return. The exchange rate therefore rises. • The appreciating dollar encourages imports and discourages exports; so X - IM falls. The U.S. therefore winds up with an inflow of capital and an increase in its trade deficit. • In the figure the two effects of the exchange rate appreciation are that: aggregate supply shifts outward So to S2 and aggregate demand shifts inward. This time, as you can see in the figure: P Contractionary Monetary Policy with International Capital Flows S0 A P0 P1 S2 B C D0 D1 D2 Q1 Q0 Real GDP International capital flows increase the power of monetary policy. INTERNATIONAL ASPECTS OF DEFICIT REDUCTION Summary of effects of fiscal policy in an open economy: • G up or T down => AD rises => interest rates rise => dollar appreciation => imports up and exports down => AD falls (Thus, the initial AD rise is not as large as in a closed economy.) • G down or T up => AD falls => interest rates fall => dollar depreciation => imports down and exports up => AD rises (Thus, the initial drop in AD is not as large as in a closed economy.) Summary of effects of Monetary policy in an open economy: • Tightening monetary policy => interest rate rises => I falls (AD falls) => dollar appreciation => imports up and exports down => AD falls (Thus, the initial AD decrease is larger compared to a closed economy.) • Expansionary monetary policy => interest rate falls => I rises (AD rises) => dollar depreciation => imports down and exports up => AD rises (Thus, the initial AD increase is larger compared to a closed economy.) • Now let us put the open economy theory to work by applying it to the events of the 1990s when fiscal policy was tightened and monetary policy was eased. Should reducing the budget deficit (or raising the surplus) strengthen or weaken the dollar? • The U.S. government transformed its huge budget deficit into a notable surplus during the 1990s by raising taxes and cutting expenditures. • This should lower the real interest rate, make the dollar depreciate, reduce real GDP, and be less disinflationary than normal because of the falling dollar. • But the Fed practiced expansionary policy and lowered interest rates. This should lead to a depreciation of the dollar and an increase in real GDP and Inflation. Expected Effects of Policy Fiscal Variable Contraction Real interest rate Exchange rate Net exports + Real GDP Inflation - Monetary Expansion Net Effect - - + + + + ? ? Results in the 1990s 1. 2. 3. 4. Interest rates fell. The U.S. economy expanded. Inflation fell. Exchange rate fell in 93 – 95; but rose thereafter in the nineties. 5. Net exports went from -20 billion in 1992 to -$221 in 1998. (4 and 5 were not consistent with projections) Expected Effects of Policy in 2002 2003 Fiscal Variable Expansion Real interest rate + Exchange rate + Net exports Real GDP + Inflation + Monetary Expansion Net Effect - ? + + + ? ? + + Link between the Budget Deficit and the Trade Deficit GDP: 1. Y = C + I + G + (X – M) GDP can be consumed, saved or taxed 2. Y = C + S + T 3. C + I + G + (X – M) = C + S + T Rearranging terms: 4. X – M = (S – I) – (G – T): accounting definition (Meaning: two sources of a trade deficit) 1. A government budget deficit 2. An excess of investment over saving Back to the 90’s 1. government deficit (G – T) fell; thus trade deficit (X – M) should fall– ceteris paribus 2. ceteris paribus does not hold since S – I is also important. (I boomed but S fell): (S – I) moved in a negative direction, causing an increase in the trade deficit . Expected Effects of Policy in 2004 Variable Real interest rate Exchange rate Net exports Real GDP Inflation Fiscal Expansion Monetary Contraction Net Effect + + + + + + + - + ? ? Historically, trade deficit has been a problem • Economy as a whole -- the government and the private sector -- are consuming more than they are producing. • Upshot: U.S. must borrow the difference from foreigners. • The deficit simply mirrors the required capital inflows from foreigners. Two possible interpretations: 1. Capital inflows create debts requiring future interest and principal payments. (Future generations will have to pay the debt.) 2. US is an attractive place to invest capital. Investors want to invest (lend) to the US. This will tend toward a higher dollar and also the tendency will be to reduce net exports. In this case though, this should be viewed as a strength, not a weakness. Reducing the Trade Deficit • Tighten Fiscal Policy and loosen monetary policy. • Other countries need to grow faster. • Raise domestic saving or reduce domestic investment. • Raise tariffs and quotas as a form of protectionism