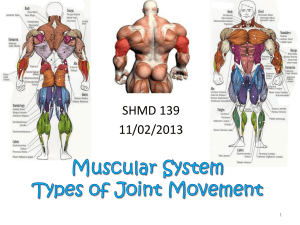

joints and movement types

advertisement

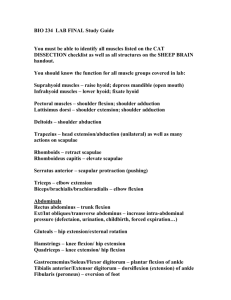

JOINTS AND MOVEMENT TYPES Axes of rotation Complete the table below KEY TERM Planes and axes of movement DEFINITION EXAMPLE Annotate the drawings below as you watch the video. Include the key terms in the boxes. FRONTAL PLANE ANTEROPOSTERIOR AXIS ABDUCTION ADDUCTION SAGITTAL PLANE TRANSVERSE AXIS FLEXION EXTENSION TRANSVERSE PLANE VERTICAL AXIS MEDIAL ROTATION LATERAL ROTATION Joint movements Label the diagrams below with the different terms to describe joint movements. Words may be used more than once. circumduction abduction adduction pronation supination eversion inversion rotation flexion extension dorsiflexion plantarflexion Movements at each joint Joint Wrist Movements possible Flexion Extension Radio/Ulnar Pronation Supination Elbow Flexion Extension Shoulder Spine Hip Knee Ankle Type of joint Flexion Extension Horizontal flexion Horizontal extension Abduction Adduction Rotation Circumduction Flexion Extension Lateral flexion Flexion Extension Abduction Adduction Rotation Flexion Extension Dorsiflexion Plantar flexion Sporting example Movement at joints – practical activity Joint movements – sporting examples Muscles and movement review 1. What movement does iliopsoas produce? 2. Label the 4 parts of quadriceps 3. What movement does the quadriceps produce at the knee? 4. Label the 3 parts of the hamstrings 5. Which muscles produce plantarflexion – pointing toes? 6. Which muscle produces inversion? 7. What are the movements of the trapezius? 8. When you turn your head to look at someone next to you – what is this called? 9. Which are the only two joints that can perform circumduction? Why? 10. What muscle is being used as you straighten out from a pike dive? 11. What two movements does the triceps brachii produce? 12. What is the main muscle which causes knee flexion? 13. What is the main muscle which causes hip extension? 14. Describe the six key parts of the spine? How many vertebrae are at each section What factors affect the range of motion (ROM) at a joint? 1. 2. 3. 4. Types of muscle contraction Outline the different types of muscle contractions and give an example of each. ROLES OF MUSCLES IN JOINT MOVEMENTS Define the following key terms Key term agonist (prime mover) Definition Example (bicep curl) antagonist fixator Synergist (neutralizer) reciprocal inhibition Complete the following table MOVEMENTS 1) Wrist flexion AGONIST (prime mover) ANTAGONIST (relaxed) Flexor Digitorum Extensor Digitorum Biceps Brachii Triceps Brachii Anterior Deltoid Posterior Deltoid Pectoralis Major Latissimus Dorsi Latissimus Dorsi Deltoid (middle) Wrist extension 2) Elbow flexion Elbow extension 3) Shoulder flexion Shoulder extension Shoulder adduction Pectoralis major 4) Shoulder abduction Deltoid (middle) Spine/ Trunk flexion Rectus Abdominis Spine extension – 5) Erector Spinae Rectus Abdominis Hip flexion – Hip extension – 6) Knee flexion – Gluteus Maximus Iliopsoas Hamstrings Quadriceps Hamstrings Quadriceps Gastrocnemius Knee extension – 7) Dorsiflexion – Plantarflexion – Gastrocnemius Tibialis Anterior Soleus Core Stability Core stability muscles contract to act as stabilisers, prior to movement. Which are the core stability muscles? A strong core stability gives you: A more stable centre of gravity/mass Reduced risk of injury/pain (especially lower back) Improved posture and body/spine alignment Creates a more stable platform allowing more efficient movement Weak core muscles can make you susceptible to poor posture, muscular instability/injuries, nerve irritation & lower back pain Give some examples of training you can do to help improve core stability...... Read the following article about DOMS 1. Read the article about DOMS individually 2. Highlight any key terms that you have met in the SEHS course so far 3. Divide the text mentally into 4 main themes 4. Using the graphic organizer provided, give each theme a main heading 5. In the space below the main heading, summarise the relevant information from the text using no more than 3 BULLET POINTS 6. To finish your analysis, write 3 full meaningful sentences that summarise the text in the final box provided 3 key ideas 25 July 2012 BBC FUTURE – Medical Myths Claudia Hammond http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20120724-you-must-stretch-before-exercise/all Is stretching before and after exercise necessary? We’re all told to limber up to prevent injury and pain. But is there any evidence that it actually works? Earlier this year, I was making a programme about Olympic sprinters and I was lucky enough to attend a training session in Jamaica where former 100 metres world record holder Asafa Powell and his teammates worked through a lengthy series of meticulous leg and abdomen stretches afterwards. An hour later they finally completed them. If you’re going to push your body to the limits of what’s humanly possible and run 100m in less than ten seconds I can see why you need you make sure your muscles are well and truly warmed up and cooled down. But these are elite athletes – the world’s best. What if you’re not quite that good and are just going for a leisurely run? We are often told that stretching muscles is the best way to avoid aching limbs the following day, or to minimise the risk of injury. I’m sure you feel better after stretching your calves or thighs. The problem is that no one seems to agree on the optimum time to do them. In Australia there is an emphasis on stretching before you start exercising. In Norway it’s afterwards. Some people swear by doing both. But what is the evidence that it really makes a difference whether you do it all? Sore point There are two separate issues here. First is soreness, and by that I mean the kind of tenderness that creeps into your muscles a day or two after you’ve exercised. The kind that painfully reminds you of your previous exertions every time you move (followed rapidly by a vow never to do them again). This is especially likely to happen if you’ve done an activity you’ve not done for a while, such as riding a bike for the first time in months because the weather has finally picked up. This type of delayed discomfort reaches its peak after two days, but the idea that stretching will prevent it stems from outdated theories as to its cause. It used to be thought that exercising for the first time after weeks or months caused the muscles to spasm, reducing the flow of the blood to the muscles, and resulting in pain. The theory went that stretching the muscles would reduce the spasm and restore the blood flow. But more recently physiologists have established that this isn’t the cause of this form of muscle soreness. Some now believe that the pain results from elongation of sarcomeres, the parts of the muscle that help them to contract. They contain thick and thin filaments, which slide past each other; in principle stretching could still help the filaments to slide smoothly, but the evidence is surprisingly limited. There are only a small number of randomised controlled studies on stretching and exercise. A recent Cochrane Review found just twelve, and all but one had fewer than 30 participants. For the most part these studies found stretching had little impact on soreness. By far the largest study, carried out in Australia and Norway, with more than two thousand participants, found there was a small reduction in soreness in those in the stretching group. Even then this effect was very small – 24% of the stretchers were bothered by soreness the following week compared with 32% of people who didn’t stretch. Injury time If stretches make no difference, or at best a small difference to soreness, how about injury? I’d always assumed the idea was that if you gently loosened your muscles by stretching, then you wouldn’t suddenly pull a hamstring when you ran for a bus or leapt a puddle. Just six randomized controlled trials have been conducted on the prevention of injuries, some with the general public, others with members of the armed forces undergoing training. Overall there was no difference in the number of leg injuries sustained in those who did or did not stretch. So what are we to make of these results that conclude stretching has little or no impact, when it’s something we are all encouraged to do? I turned to the author of one of those reviews, Rob Herbert, from the George Institute in Australia, to get his advice. He gave me an answer which, as someone who can’t be bothered to stretch before I go running, I have to confess I like. He said if you enjoy stretching then it’s fine to carry on and it will do you no harm, but that taking all the evidence into account, it probably won’t help much. I was glad to see he puts his evidence-based results into practice in his own life. When I interviewed him from a studio in Sydney he had just come from playing football. Had he stretched beforehand? No.