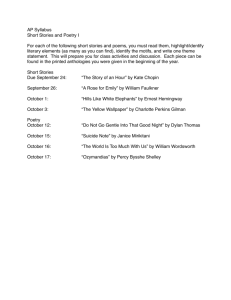

Lecture One of Book Two The Romantic Period William Wordsworth

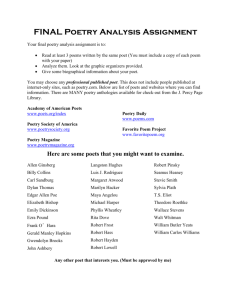

advertisement

Lecture One of Book Two

The Romantic Period;

William Wordsworth

I. Introduction

• Romanticism:

• literary and artistic movements of the late 18th and 19th century.

• a rejection of the precepts of order, calm, harmony, balance,

idealization, and rationality that typified classicism in general and

late 18th-century neoclassicism in particular.

• a reaction against the Enlightenment and against 18th-century

rationalism and physical materialism in general.

• Inspired in part by the libertarian ideals of the French Revolution,

• believed in a return to nature and in the innate goodness of humans,

as expressed by Jean Jacques Rousseau;emphasized the individual,

the subjective, the irrational, the imaginative, the personal, the

spontaneous, the emotional, the visionary, and the transcendental.

• interest in the medieval, exotic, primitive, and nationalistic.

• From William Wordsworth and S.T. Coleridge's Lyrical Ballads in

1798 to the death of Sir Walter Scott and the passage of the first

reform bill in the Parliament in 1832.

II. Background knowledge of

Romanticism

• 1. Historical background

• (1) Romanticism as a literary movement appeared in England from

the publication of Lyrical Ballads in 1798 to the death of Sir Walter

Scott and the passage of the first reform bill in the Parliament in

1832.

• (2) The American and French revolutions greatly inspired the

English people fighting for Liberty, Equality and Fraternity.

• (3) The Industrial Revolution brought great wealth to the rich but

worsened the working and living conditions of the poor, which gave

rise to sharp conflicts between capital and labor.

• (4) In England the primarily agricultural society was replaced by a

modern industrialized one.

• (5) Political reforms and mass demonstrations shook the foundation

of aristocratic rule in Britain.

• 2. Cultural background

• Inspiration for the romantic approach initially came from two great

shapers of thought, French philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau

and German writer Johann Wolfgang yon Goethe. It is Rousseau

who established the cult of the individual and championed the

freedom of the human spirit; his famous announcement was "I felt

before I thought". Goethe and his compatriots extolled the romantic

spirit as manifested in German folk songs, Gothic architecture, and

the plays of English playwright William Shakespeare.

• (2) The Romantic Movement expressed a more or less negative

attitude toward the existing social and political conditions, for the

romantics saw both the corruption and injustice of the feudal

societies and the fundamental inhumanity of the economic, social

and political forces of capitalism.

• (3) Romanticism constitutes a change of direction from attention to

the outer world of social activities to the inner world of the human

spirit, tending to see the individual as the very center of all life and

all experience.

• (4) In literature, the romantics shifted their emphasis from reason,

which was a dominant mode of thinking among the 18th-century

writers and philosophers, to instinct and emotion, which made

literature most valuable as an expression of an individual's unique

feelings.

• 3. Features of the romantic literature

• (1) Expressiveness: Instead of regarding poetry as "a mirror to

nature", the romantics hold that the object of the artist should be the

expression of the artist's emotions, impressions, or beliefs.

• The role of instinct, intuition, and the feelings of "the heart" is

stressed instead of "neoclassicists" emphasis on "the head", on

regularity, uniformity, decorum, and imitation of the classical writers.

poetry as "the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings".

• (2) Imagination: emphasis on the creative function of the imagination,

seeing art as a formulation of intuitive, imaginative perceptions.

• (3) Singularity: a strong love for the remote, the unusual, the strange,

the supernatural, the mysterious, the splendid, the picturesque, and

the illogical.

• (4) Worship of nature: Romantic poets see in nature a revelation of

Truth, the "living garment of God". nature to them is a source of

mental cleanness and spiritual understanding.

• (5) Simplicity: turn to the humble people and the everyday life for

subjects, employing the commonplace, the natural and the simple as

their materials; take to using everyday language spoken by the

rustic people as opposed to the poetic diction used by neoclassic

writers.

• (6) The romantic period is an age of poetry with Blake, Wordsworth,

Coleridge, Byron, Shelley and Keats as the major poets.

III. William Wordsworth

• William Wordsworth.

• the representative poet of the early romanticism

• born in 1770 in a lawyer's family at

Cockermouth, Cumberland.

• His mother died when he was only eight. His

father followed her six years later.

• The orphan was taken in charge by relatives,

who sent him to school at Hawkshead in the

beautiful lake district in Northwestern England.

• the unroofed school of nature attracted him

more than the classroom, and he learned more

eagerly from flowers and hills and stars than

from his books.

• He studied at Cambridge from 1787 to 1791.

While at university, he associated with those

young Republicans roused by the French

Revolution.

• In the year 1790-1792 he twice visited France.

On his second visit he became acquainted with

Beaupuy, an army officer of the new-born

Republic of France, who kindled the heart of the

young English man with a spirit of revolt against

all social iniquities and a sympathy for the poor,

humble folk.

• In 1795, Wordsworth settled, with his sister

Dorothy, at Racedown in Somersetshire. They

lived a frugal life and Dorothy, as his confidante

and inspirer, made him turn his eyes to ' the face

of nature' and take an interest in the peasants

living in their neighbourhood.

• In 1797 be made friends with Coleridge. Then

they lived together in the Quantock Hills,

Somerset, devoting their time to writing of poetry.

• In 1798 they jointly published the “Lyrical

Ballads”. Coleridge’ s contribution was his

masterpiece ' The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'.

The majority of poems in this collection, however,

were written by Wordsworth.

• The publication of the ' Lyrical Ballads' marked

the break with the conventional poetical tradition

of the l8th century, i.e. with classicism, and the

beginning of the Romantic revival in England.

• In the Preface to the "Lyrical Ballads', Wordsworth set forth his

principles of poetry.

• "all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feeling.'

individual sensations, i.e. pleasure, excitement and enjoyment, as

the foundation in the creation and appreciation of poetry.

• Poetry “takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility."

• A poet's emotion extends from human affairs to nature. Tranquil

contemplation of an emotional experience matures the feeling and

sensation.

• The function of poetry lies in its power to give an unexpected

splendour to familiar and commonplace things, to incidents and

situations from common life just as a prism can give a ray of

commonplace sunlight the manifold miracle of colour.

• Ordinary peasants, children, even outcasts, all may be used as

subjects in poetical creation.

• As to the language used in poetry, Wordsworth "endeavoured to

bring his language near to the real language of men”.

• The Preface to the “Lyrical Ballads” as the manifesto of the English

Romanticism.

• Wordsworth, Coleridge and Southey have often been mentioned as

the “Lake Poets” because they lived in the lake district in the

northwestern part of England. The three traversed the same path in

politics and in poetry, beginning as radicals and closing as

conservatives.

• Wordsworth lived a long life and wrote a lot of poems. He was at his

best in descriptions of mountains and rivers, flowers and birds,

children and peasants, and reminiscences of his own childhood and

youth. As a great poet of nature, he was the first to find words for the

most elementary sensations of man face to face with natural

phenomena. These sensations are universal and old but, once

expressed in his poetry, become charmingly beautiful and new.

• His deep love for nature run through such short lyrics as Lines

Written in Early Spring". “To the Cuckoo” “ I Wandered Lonely as a

Cloud” .” My Heart Leaps Up”, Intimations of Immortality' and - Lines

Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey'. The last is called his

"lyrical hymn of thanks to nature:

• Wordsworth was also a masterhand in searching and

revealing the feelings of the common people.

• The themes of many of his poems were drawn from rural

life: and his characters belong to the lower classes in the

English countryside. This is so because he was

intimately acquainted with rural life and believed that in

rural conditions man's elementary feelings find a better

soil than in town life and can be better cultivated and

strengthened in constant association with nature.

• (' The Solitary Reaper' ). in depicting the naivety of

simple peasant children (' We Are Seven' ) and in

delineating with deep sympathy the sufferings of the poor.

humble peasants ("Michael'," The Ruined Cottage'.

"Simon Lee", and "The Old Cumberland Beggar' ).

• His "Lucy" poems are a series of short pathetic lyrics on

the theme of harmony between humanity and nature.

• Wordsworth's poetry is distinguished by the simplicity

and purity of his language. "His theory and practice in

poetical creation started from a dissatisfaction With the

social reality under capitalism, and hinted at the thought

of' back to nature ' and back to the patriarchal system of

the old time"

• "The Prelude" is Wordsworth’s autobiographical poem, in

14 books, which was written in 1799-1805 but not

published until 1850. it is the spiritual record of the poet's

mind, honestly recording his own intimate mental

experiences which cover his childhood, school days,

years at Cambridge, his first impressions of London, his

first visit to France, his residence in France during the

Revolution, and his reaction to these various

experiences, showing the development of his own

thought and sentiment.

Points of view

• (1) Politically Wordsworth was a radical democrat in the early days,

attracted to the slogans of liberty, equality and fraternity but became

a conservative in his later years. However, in his whole life, he held

a critical attitude towards the government and the upper class. He

was strongly against the Industrial Revolution which, he believed,

had caused the miseries of the poor people and destroyed the quiet

simple life of the country people. He had great sympathy for the poor

and regarded them as the victims of the fortune-hunting capitalists.

• (2) Literarily, he was strongly against the neoclassical poetry,

especially that of Dryden, Pope and Johnson, and tried to restore

the tradition of Spenser, Shakespeare and Milton. He was the

leading figure of the English romantic poetry. He thought the source

of poetic truth was the direct experience of the senses. Poetry, he

asserted, originated from "emotion recollected in tranquility". He

maintained that the scenes and events of everyday life and the

speech of ordinary people were the raw material of which poetry

could and should be made. The most important contribution he hag

made is that he has not only started the modern poetry, the poetry of

the growing inner self, but also Changed the course of English

poetry by using ordinary speech of the language and by advocating

a return to nature.

2. Major works

• Tintern Abbey

Composed A Few Miles Above Tintern

Abbey, On Revisiting The Banks Of The

Wye During A Tour. July 13, 1798.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

FIVE years have past; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters! and again I hear

These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs

With a soft inland murmur. -- Once again

Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs,

That on a wild secluded scene impress

Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect

The landscape with the quiet of the sky.

The day is come when I again repose

Here, under this dark sycamore, and view

These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts,

Which at this season, with their unripe fruits,

Are clad in one green hue, and lose themselves

'Mid groves and copses. Once again I see

These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Of sportive wood run wild: these pastoral farms,

Green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke

Sent up, in silence, from among the trees!

With some uncertain notice, as might seem

Of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods,

Or of some Hermit's cave, where by his fire

The Hermit sits alone.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

These beauteous forms,

Through a long absence, have not been to me

As is a landscape to a blind man's eye:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and 'mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind,

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

With tranquil restoration: -- feelings too

Of unremembered pleasure: such, perhaps,

As have no slight or trivial influence

On that best portion of a good man's life,

His little, nameless, unremembered, acts

Of kindness and of love. Nor less, I trust,

To them I may have owed another gift,

Of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world,

Is lightened: -- that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on, -Until, the breath of this corporeal frame

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

If this

Be but a vain belief, yet, oh! how oft -In darkness and amid the many shapes

Of joyless daylight; when the fretful stir

Unprofitable, and the fever of the world,

Have hung upon the beatings of my heart -How oft, in spirit, have I turned to thee,

O sylvan Wye! thou wanderer thro' the woods,

How often has my spirit turned to thee!

And now, with gleams of half-extinguished thought,

With many recognitions dim and faint,

And somewhat of a sad perplexity,

The picture of the mind revives again:

While here I stand, not only with the sense

Of present pleasure, but with pleasing thoughts

That in this moment there is life and food

For future years. And so I dare to hope,

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Though changed, no doubt, from what I was when first

I came among these hills; when like a roe

I bounded o'er the mountains, by the sides

Of the deep rivers, and the lonely streams,

Wherever nature led: more like a man

Flying from something that he dreads, than one

Who sought the thing he loved. For nature then

(The coarser pleasures of my boyish days,

And their glad animal movements all gone by)

To me was all in all. -- I cannot paint

What then I was. The sounding cataract

Haunted me like a passion: the tall rock,

The mountain, and the deep and gloomy wood,

Their colours and their forms, were then to me

An appetite; a feeling and a love,

That had no need of a remoter charm,

By thought supplied, nor any interest

Unborrowed from the eye. -- That time is past,

And all its aching joys are now no more,

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

And all its dizzy raptures. Not for this

Faint I, nor mourn nor murmur, other gifts

Have followed; for such loss, I would believe,

Abundant recompence. For I have learned

To look on nature, not as in the hour

Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes

The still, sad music of humanity,

Nor harsh nor grating, though of ample power

To chasten and subdue. And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man;

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things. Therefore am I still

A lover of the meadows and the woods,

And mountains; and of all that we behold

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

From this green earth; of all the mighty world

Of eye, and ear, -- both what they half create,

And what perceive; well pleased to recognise

In nature and the language of the sense,

The anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse,

The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul

Of all my moral being.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Nor perchance,

If I were not thus taught, should I the more

Suffer my genial spirits to decay:

For thou art with me here upon the banks

Of this fair river; thou my dearest Friend,

My dear, dear Friend; and in thy voice I catch

The language of my former heart, and read

My former pleasures in the shooting lights

Of thy wild eyes. Oh! yet a little while

May I behold in thee what I was once,

My dear, dear Sister! and this prayer I make,

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Knowing that Nature never did betray

The heart that loved her; 'tis her privilege,

Through all the years of this our life, to lead

From joy to joy: for she can so inform

The mind that is within us, so impress

With quietness and beauty, and so feed

With lofty thoughts, that neither evil tongues,

Rash judgments, nor the sneers of selfish men,

Nor greetings where no kindness is, nor all

The dreary intercourse of daily life,

Shall e'er prevail against us, or disturb

Our cheerful faith, that all which we behold

Is full of blessings. Therefore let the moon

Shine on thee in thy solitary walk;

And let the misty mountain-winds be free

To blow against thee: and, in after years,

When these wild ecstasies shall be matured

Into a sober pleasure; when thy mind

Shall be a mansion for all lovely forms,

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Thy memory be as a dwelling-place

For all sweet sounds and harmonies; oh! then,

If solitude, or fear, or pain, or grief,

Should be thy portion, with what healing thoughts

Of tender joy wilt thou remember me,

And these my exhortations! Nor, perchance -If I should be where I no more can hear

Thy voice, nor catch from thy wild eyes these gleams

Of past existence -- wilt thou then forget

That on the banks of this delightful stream

We stood together; and that I, so long

A worshipper of Nature, hither came

Unwearied in that service: rather say

With warmer love -- oh! with far deeper zeal

Of holier love. Nor wilt thou then forget,

That after many wanderings, many years

Of absence, these steep woods and lofty cliffs,

And this green pastoral landscape, were to me

More dear, both for themselves and for thy sake!

She Dwelt Among Untrodden Ways

•

•

•

•

She dwelt among the untrodden ways

Beside the springs of Dove,

Maid whom there were none to praise

And very few to love:

•

•

•

•

A violet by a mosy tone

Half hidden from the eye!

---Fair as a star, when only one

Is shining in the sky.

•

•

•

•

She lived unknown, and few could know

When Lucy ceased to be;

But she is in her grave, and, oh,

The difference to me!

I traveled among unknown men

•

•

•

•

I TRAVELLED among unknown men,

In lands beyond the sea;

Nor, England! did I know till then

What love I bore to thee.

•

•

•

•

'Tis past, that melancholy dream!

Nor will I quit thy shore

A second time; for still I seem

To love thee more and more.

•

•

•

•

Among thy mountains did I feel

The joy of my desire;

And she I cherished turned her wheel

Beside an English fire.

• Thy mornings showed, thy nights concealed

• The bowers where Lucy played;

• And thine too is the last green field

• That Lucy's eyes surveyed.

I wandered lonely as a cloud

•

•

•

•

•

That That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils:

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

•

•

•

•

•

•

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

•

•

•

•

•

•

The waves beside them danced; but they

Outdid the sparkling waves in glee;

A poet could not but be gay;

In such a jocund company;

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

•

•

•

•

•

•

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

Sonnet: Composed upon Westminster Bridge,

September 3, 1802

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Earth has not anything to show more fair:

Dull would he be of soul who could pass by

A sight so touching in its majesty:

This City now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

•

•

•

•

•

•

Never did sun more beautifully steep

In his first splendour, valley, rock, or hill;

Ne'er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! The very houses seem asleep;

And all that mighty heart is lying still!

Sonnet: London,1802

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour;

England hath need of thee: she is a fen

Of stagnant waters: altar, sword, and pen,

Fireside, the heroic wealth of hall and bower,

Have forfeited their ancient English dower

Of inward happiness. We are selfish men;

Oh! raise us up, return to us again;

And give us manners, virtue, freedom, power.

Thy soul was like a Star, and dwelt apart;

Thou hadst a voice whose sound was like the sea:

Pure as the naked heavens, majestic, free,

So didst thou travel on life's common way,

In cheerful godliness; and yet thy heart

The lowliest duties on herself did lay.

The Solitary Reaper

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

BEHOLD her, single in the field,

Yon solitary Highland Lass!

Reaping and singing by herself;

Stop here, or gently pass!

Alone she cuts and binds the grain,

And sings a melancholy strain;

O listen! for the Vale profound

Is overflowing with the sound.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

No Nightingale did ever chaunt

More welcome notes to weary bands

Of travellers in some shady haunt,

Among Arabian sands:

A voice so thrilling ne'er was heard

In spring-time from the Cuckoo-bird,

Breaking the silence of the seas

Among the farthest Hebrides.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Will no one tell me what she sings?-Perhaps the plaintive numbers flow

For old, unhappy, far-off things,

And battles long ago:

Or is it some more humble lay,

Familiar matter of to-day?

Some natural sorrow, loss, or pain,

That has been, and may be again?

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Whate'er the theme, the Maiden sang

As if her song could have no ending;

I saw her singing at her work,

And o'er the sickle bending;――

I listen'd, motionless and still;

And, as I mounted up the hill,

The music in my heart I bore,

Long after it was heard no more.

• (1) Lyrical Ballads (1798)

• the landmark in English literature, for it started a poetical revolution

by using the common, simple and colloquial language in poetry. The

poems were written in the spirit and in the pattern of the early

storytelling ballads. They are simple tales about simple life told in

simple style and simple language to express the simple emotions in

simple lyricism.

• (2) Preface to Lyrical Ballads (1802)

• The Preface deserts, its reputation as a manifesto in the theory of

poetry. Most discussions of the Preface focused on his assertions

about the valid language of poetry, that is, "all good poetry is the

spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings." He attributed to

imaginative literature the primary role in keeping man emotionally

alive and morally sensitive, i. e. keeping him essentially human, in

the face of the pressures of a technological and increasingly urban

society. He claimed that the great subjects of poetry were "the

essential passions of the heart" and "the great and simple

affections" as these qualities interact with "the beautiful and

permanent forms of nature" and are expressed in a "naked and

simple" language that is "adapted to interest mankind permanently."

• (3) Prelude, or Growth of a poet's Mind(1850)

• The Prelude is Wordsworth's masterpiece, the greatest

and most original long poem since Milton's Paradise Lost.

It is a personal history which turns on a mental crisis and

recovery, and for such a narrative design the chief

prototype is not the classical or Christian epic, but the

spiritual autobiography of crisis. The recurrent metaphor

is that of journey, whose end is its beginning, and in

which it turns out that the end of the journey is "to arrive

where we started / And know the place for the first time".

The journey goes through the poet's personal history,

carrying the metaphorical meaning of his interior journey

and questing for his lost early self and the proper

spiritual home. The poem charts this growth from infancy

to manhood. We are shown the development 0f human

consciousness under the sway of an imagination united

to the grandeur of nature.

• 3. Special features

• (1) best at the truthful presentation of nature. He not only sees

clearly and describes accurately, but penetrates to the heart of

things and always finds some exquisite meaning that is not written

on the surface. He gives the reader the very life of nature and the

impression of some personal spirit.

• (2) The theme is about incidents and situations of common life

(generally "low and rustic"). Wordsworth considers that man is not

apart from nature, but is the very "life of her life". So he thinks the

common life is the only subject of literary interest.

• (3) Wordsworth advocates a return to nature. According to him,

society and the crowded unnatural life of cities tend to weaken and

pervert humanity; and a return to nature and simple living is the only

remedy for human wretchedness. He Shows sympathy to the

common people.

• (4)The language used in his poetry is a selection of language really

used by men. In other words, he uses simple, colloquial language in

poetry.

• "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud"

• (A) Main idea

• The poem is crystal clear and lucid. By recounting a little

episode, the poet gives a description of the scene and of

the feelings that match it. Then he abstracts the total

emotional value of the experience and concludes by

summing that up. Below the immediate surface, we find

that all the realistic details of the flowers, the trees, the

waves, the wind, and all the accompanying sensations of

active joy, are absorbed into an over-all concrete

metaphor, the recurrent image of the dance, which

appears in every stanza. The flowers, the stars, the

waves are units in this dancing pattern of order in

diversity, of linked eternal harmony and vitality. Through

the revelation and recognition of his kinship with nature,

the poet himself becomes as it were a part of the whole

cosmic dance.

• (B) Comprehension notes

• (a) "I wandered lonely as a cloud / That floats on high o'er vales and

hills": While the poet was taking a walk in the woods, he felt lonely

and detached from earthly fellowship just like a lonely cloud,

wandering and floating in the sky.

• (b) "When all at once I saw a crowd, / A host, of golden daffodils... ";

Suddenly the poet sees the host of dancing daffodils. The daffodils

remind him of the stars at night in brightness and multitude; they

match the waves in radiance and gaiety. In a flash, the poet's

loneliness is transformed into fellowship; he becomes a part of all

this "jocund company".

• (c) "Fluttering and dancing in the breeze": The dancing image (such

as fluttering, dancing, shining, twinkling, sparkling and tossing)

recurs in every stanza of the poem, revealing a sense of joy and

unity and continuity in the natural elements of air, water and earth.

• (d) "What wealth the show to me had brought": The moment of

vision is a revelation, an intuition of a vital union between him and

the forces around him, which enriches his life forever.

• (e) "They flash upon that inward eye": Through that "inward eye" of

memory, other moods of loneliness, and listlessness can be

animated with the sense of fulfillment which was captured on that

first spring morning. It is an intensely personal poem. It creates a

purely subjective experience. The poet tells us about the daffodils in

order to tell us something about himself.

• (f) In the last two stanzas, we notice that the speaker uses in

succession five words denoting joy ("glee", "gay", "jocund", "bliss",

and "pleasure") in a crescendo that suggests the intensity of the

speaker's happiness. Although Wordsworth uses various words to

indicate joy, he occasionally repeats rather than varies his diction.

The repetitions of the words for seeing ("saw", "gazed") inaugurate

and sustain the imagery of vision that is Central to the poem's

meaning; the forms of the verb to dance ("dancing", "dance", and

"dances") suggest both that the various elements of nature are in

harmony with one another and that nature is also in harmony with

man. The poet conveys this by bringing the elements of nature

together in pairs: daffodils and wind (stanza 1); daffodils and stars

(stanza 2); water and wind (stanza 3). Nature and man come

together explicitly in stanza 4 when the speaker says that his heart

dances with the daffodils. A different kind of repetition appears in the

movement from the "loneliness" of line one to the "solitude" or line

22.

• Both words denote an alone-ness, but they suggest a radical

difference in the solitary person's attitude to his state of being alone.

The poem moves from the sadly alienated separation felt by the

speaker in the beginning to his joy in recollecting the natural scene,

a movement framed by the words "lone" and "solitude". An

analogous movement is suggested within the final stanza by words

"vacant" and "fills". The emptiness of speaker's spirit is transformed

into a fullness of feeling as he remembers the daffodils.

• (2) "Composed upon Westminster Bridge" (September3,

1802)

• (A) Main idea

• The poem is a kind of dramatic monologue, in the

present tense, to express immediate pleasure in the eye

and ear and to celebrate qualities of a particular personal

experience. The tone is solemn but not heavy. The first 8

lines present a very beautiful picture of London in the

early morning, with its "ships, towers, domes, theatres,

and temples" glittering "in the smokeless air". By linking

the city buildings with the open fields and the sky, the

speaker tries to put the stress to the scenes of the whole

country in which the city is only a part. In doing so, the

speaker intends to connect the valley, rock and hill and

river in the next few lines to present the natural beauty.

• (B) Comprehension notes

• (a) "This City now doth, like a garment, wear / The beauty of the

morning": The poet chose the word "wear" to say that the city wears

its beauty just like people wearing a garment. Generally people wear

something for two purposes: one is to keep them warm; the other is

to cover up something ugly. The beauty of the morning might be the

calm and the quiet of the city. Thus, the speaker would observe the

city in such a way that his eyes as if went on tiptoe over the scene,

anxious not to awaken the city into the ugliness and confusion of

noisy activities he hated.

• (b) "All bright and glittering in the smokeless air": The air of London

was severely polluted during the early Industrial Revolution in the

19th century. Smokeless air could only be seen in the early morning.

• (c) "The river glideth at his own sweet will": The river runs freely, for

there is no barges or steamers to hinder its running in the early

morning. Here the river is personified so that it has its own will.

• (3) "She Dwelt Among the Untrodden Ways"

• (A) Main idea

• This is One of the five well-known "Lucy poems"

by Wordsworth. It tells us that since Lucy lived

remote from the great world, her death passed

unnoticed. Few people knew her, and the few

simple, unlettered folk who knew her lacked the

means to set forth to the world the tributes due

to her. Yet, though Lucy's passing made no

difference to the great world, it has made all the

difference to her lover, who speaks the poem.

The poem is written with rare elusive beauty of

simple lyricism and haunting rhythm.

• (B) Comprehension notes

• (a) "She dwelt among the untrodden ways": The speaker tries to say

that the lowly country girl led her simple life of obscurity far away

from "the madding crowd".

• (b) "A violet by a mossy stone / Half hidden from the eye! /--Fair as a

star, when only one / Is shining in the sky": By using a metaphor and

a simile, the poet compares Lucy with a Violet, a wild flower growing

by a mossy stone, and a fair star, shining in the sky. The two

comparisons are meant to enhance Lucy's charm by associating her

with such attractive objects as flowers and stars. Lucy's natural

charm, like that of the violet, was derived from her modesty; She,

too, was "half-hidden from the eye", obscure and unnoticed. Though

Lucy was, to the world, as completely obscure as the modest flower

in the shadow of the mossy stone, to the eye of her lover she was

the only star in his heaven, shining like the planet of love itself.

• (c) "The difference to me": This phrase reveals the speaker's strong

love-for Lucy. Although others may be indifferent to her whether

dead or alive, he still loves her and her beauty. And her fine qualities

are also living in his memory.

• (4) "The Solitary Reaper"

• (A) Main idea

• This is a deceptively simple poem, in which

Wordsworth describes vividly and

sympathetically a young peasant girl working in

the fields and singing as she works. The plot of

the little incident is told rather straightforwardly.

Wordsworth did not experience the incident

himself; it was suggested by a passage in his

friend Thomas Wilkinson's Tour of Scotland. Yet

the short lyric is an admirable poem of a simple

peasant girl who obviously enjoys her work and

whose plaintive song leaves strong and lasting

impression upon the chance listener.

• (B) Comprehension notes

• (a) "Nightingale", "Cuckoo bird": By using both images as metaphors,

the poet compares the beautiful song, sung by the peasant girt with

those by the birds. On hearing a bird sing, we sometimes feel that

we are heating the voice of nature itself. In the similar way, we could,

in overhearing the girl's song (under the circumstances described),

feel that we were overhearing the voice of human nature itself.

• (b) "Will no one tell me what she sings": The traveler cannot make

out the words of the song, because, presumably, they are in Gaelic,

the native language of the Scottish Highlands.

• (c) "Some natural sorrow, loss, or pain, /That has been, and may be

again": Sorrows, losses and pains are the common sufferings the

poor people had in the past and may have again in their future.

• (d) "The music in my heart I bore, / Long after it was heard no more":

The music, which is both lovely and sad, touches the poet so greatly

that he can hardly forget it. With mixture of happiness and sorrow,

the poet celebrates the beautiful rural life and expresses his

sympathy for the suffering of the peasants.