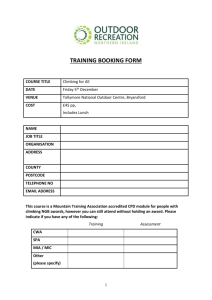

Leadership Level 1

(Paddling + Hiking)

Student Manual

(April 28, 2014)

Albi Sole and Will Woods.

© Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

Published by

The Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

KNA-101, 2500 University Drive NW.

Calgary, AB. Canada. T2N 1N4

First Published:

© 2012 and the Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

All rights reserved.

No part of this manual may be reproduced in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical

or other means, without permission in writing from the publisher

This first edition of this manual was written with assistance and guidance of the

following members of the Certification Committee of the Outdoor Council of Canada/

Conseil canadien de plein air:

Ian Sherrington (Chair)

Robyn Rankin

Jo-Anne Reynolds

Peter Tucker

Jeff Storck

Mike Crowtz

The Outdoor Council would like to thank the David Elton Outdoor Fund, The Outdoor

Centre at the University of Calgary, and the Mountain Equipment Coop for providing the

financial support that made the creation of this manual possible.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

1

Contents

Introduction ………………………………………………………………………

3

About this Course ……………………………………………………………….

4

Scope of Practice …………………………………………………………..…….

7

Chapter 1. Reasons to Become an Outdoor Leader ……………………..………..

9

Chapter 2. Pre-Event Planning (The Vision) ….………………………..…..….… 12

Chapter 3. The Water Environment and Hiking Matrixes …………..….……….

18

Chapter 4. Pre-Event Planning (Hazards and Defenses) …………………........... 25

Chapter 5. Pre-Event Planning (Team Building) ……………………..…………... 42

Chapter 6. Environmental Responsibility ……………………………..………… 46

Chapter 7. Last Minute Checks ………………………………………………….. 49

Chapter 8. Group Management ………………………………………………….. 52

Chapter 9. Situational Awareness ……………………...……………...….…........ 61

Chapter 10. Accident and Emergency Response …………………..……….…….. 64

Chapter 11. Debriefing ……………………………………………………………. 66

Appendix A. Participant - Equipment Lists ………..…….…….…………............. 72

Appendix B. Leader – Equipment List ……………………...…….…………..….. 76

Appendix C. Transport Canada regulations for watercraft………………………... 78

Appendix D. Important Components - Emergency Response Plan ………..……… 79

Appendix E. Non PFD Water Access Procedures……………..………..…………. 83

Appendix F. OCC PFD Protocol………………………………………………….. 84

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

2

Introduction

Welcome to the Outdoor Council of Canada's Level 1 Leadership Course. Perhaps this is

the first outdoor leadership course you have ever taken, or maybe you already have

substantial outdoor leadership experience. Either way, we hope that you find this course

to be an exciting and rewarding experience. Within this course you will find some of the

most current ideas on making outdoor leadership a satisfying and safe experience for you

and the people who will have the privilege of following your lead.

Outdoor environments offer a multitude of leadership possibilities ranging from a

neighbourhood walk or biology class in an urban park, to breathtaking adventures in a

remote and challenging wilderness. This course will provide a solid foundation for

planning different types of events in a multitude of outdoor environments.

Definitions

This course is designed for people leading many different types of outdoor experiences.

To avoid having to keep repeating a series of words to describe this diversity we have

chosen some words to refer to these lists. Thus:

We use the word ‘participant’ to describe the people who will be following your lead.

We use the word ‘event’ to describe all the sorts of things that you might organize for

others in either a Low Risk Water Environment or Class 1 Hiking Terrain.

We will use the phrase ‘Low Risk Natural Environments’ to describe both Low Risk

Water Environments and/or Class 1 Hiking Terrain.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

3

About this Course

The ‘Leadership Level 1’ course will provide you with a practical guide for organizing an

educational or activity-based experience in a ‘natural environment’. This course is as

much about designing and leading an event that provides a high quality experience for

your participants as it is about giving them a ‘safe’ experience. In fact, we believe that

quality and safety go hand in hand. The pre-event planning processes you need to make

before the event, the group leadership skills on the day of the event, and the de-briefing

processes that prepare you for the next event are the same processes that promote safety.

This course has two components, the leadership skills section and the technical skills

section. The leadership skills taught in this course are those needed to successfully plan

and lead a group in any sort of activity, indoors or outdoors. Since leadership has to be

attached to an activity, this version of the course has been matched with activities that

take place in ‘hiking’ or ‘paddling’ environments.

This course has been designed for people who plan to lead youth, however, a course

designed for adults would look almost identical.

This course is designed to certify people to lead others on a one-day event. Overnight

events require additional specialized skills to be managed well.

This course is designed to train and certify people to lead others in a Low Risk Water

Environment and/or Class 1 Hiking Terrain. We have defined criteria for what constitutes

a `Low Risk Water Environment` and ‘Class 1 Hiking Terrain’ in Chapter 3. Since this is

a certification course, successful completion of this course will certify you to lead others

on a one-day event in both of these environments.

This is an ‘entry level’ leadership course, which means that graduates need to be working

with other more experienced leaders upon completion of the course. This certification is

only valid while you are leading for an organization with a risk management plan written

by a suitably qualified person.

We recognize that at this time there are significant gaps in the certification available to

outdoor leaders. It is not the intention of the Outdoor Council of Canada (OCC) that

taking this course should by itself prevent you from leading others on longer events or on

events into higher risk terrain. However, this course will not provide you with any legal

safeguards regarding your leadership on such events. If you undertake such events, you

should be certain that you have the necessary additional training and experience and that

those qualifications has been validated as sufficient by other respected outdoor leaders

who agree that you have the required skills and experience.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

4

Prerequisites

Age

You must be 16 years of age or older to take this course. Those 18 or older who

successfully complete the course are designated as having a “Leadership Level

1(Paddling+ Hiking)” certification, while those 16 or 17-year old a designated as having

an “Apprentice Leadership Level 1(Paddling + Hiking)” certification. The word

“Apprentice” is automatically dropped on the graduate’s 18th birthday.

Skills

This is not a ‘technical skills’ course. By that we mean we will not be teaching paddling

or hiking skills. We expect you to come with some paddling skills; however our

expectations in this regard are not high because this course is for the entry-level leader.

In order to activate the water portion of this certification, you must have completed a

recognized relevant paddling skills certification and/or an industry standard in-house

training program, which at minimum has certified that you can:

1. Control the kind of paddle-craft you will be using for your event;

2. Perform an efficient rescue of the participants in the event of a capsize of a

participant’s paddle-craft, or your own paddle-craft, during your event;

Or, have demonstrated to a recognized paddling professional that you have these skills.

Course Requirements and Examination

Our goal is for you to pass this course. However, leadership is a big responsibility, so you

will have to exert some real effort. We can assure you that the more effort you put into

this course, the more you will take away from it.

Pre-course Reading

You will need to read this manual in advance and answer the quiz questions within it. At

the start of the course your instructor will confirm that you have done this. This will be

the time to ask your instructor for clarification if any of the material is not clear to you.

These quizzes prepare you for the final written test.

Course Participation

In order to cover a great deal of abstract material in a short time this course employs

many experiential learning exercises. Experiential learning can create a powerful learning

environment, but only if the participant is willing to become fully involved in the

experience. For maximum value you must actively participate.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

5

Field Portion

This portion of the course is not formally examined. However, we expect that you will

participate fully in the day. We also expect that you will come with the skills and

physical ability outlined in the ‘prerequisites’.

Written Test

You will write a test near the end of the last day. The mark required to pass the course

will be discussed with you at the beginning of the first day.

Pass/Fail

The written test provides an ‘objective’ measure of skills mastered. For most people this

will be the only recorded criteria for passing or failing. However, you should be aware

that in exceptional circumstances a person can fail the course based on ‘subjective’

criteria. These criteria are as follows:

An instructor can fail a person on ‘subjective’ grounds if they believe that the student:

a) Failed to demonstrate sufficient respect for the materials and/or learning processes

required for the course.

b) Failed to demonstrate sufficient respect for their fellow students or instructors.

c) Demonstrated obvious psychological distress that leads the instructor(s) to believe

that the person is struggling with psychological self-care.

d) Failed to demonstrate on the field day that they had the physical skills required to

care for themselves and their participants in a Low Risk Natural Environments

Conditions for the use of subjective criteria for failure:

a) Subjective failure will only be used under exceptional circumstances.

b) Where an instructor sees evidence during a course that leads them to suspect that

they may need to exercise their subjective judgment prerogative, and there is still

time for the student to reform their behaviour, the instructor must initiate a

discussion with the student telling him or her of their concerns and provide

specific instructions as to the change they wish to see.

c) A subjective failure can be appealed to the Outdoor Council Certification

Committee whose ruling shall be final.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

6

LL1 (Paddling + Hiking) Scope of Practice

The Leadership Level 1 (Paddling + Hiking) certification certifies a person to lead groups into a Low Risk Water

Environment (see page 19) on a one- day paddle providing the following conditions are met:

1) The Level 1 (Paddling + Hiking) Leader is being adequately supervised. Adequate supervision will typically mean:

a) The supervisor has 5 or more years of leadership experience, of which 2 years have been with participants of

the same demographic as those the LL1 graduate is leading.

b) The performance of the LL1 leader is actively monitored through direct observation from time to time and

there is a comprehensive trip reporting system in place.

c) The supervisor takes steps to ensure that the trip reporting system is capturing the information required to form

a judgment of the leader’s performance.

d) The supervisor is committed to creating participant centered programming.

2) The Level 1 (Paddling + Hiking) Leader has inspected every part of the terrain that their group will be using at

least once in the previous 12 months.

3) The Level 1 (Paddling) Leader has completed a recognized, relevant paddling skills certification and/or an industry

standard in-house training program, which at minimum has certified that he/she can:

1. control the kind of paddlecraft he/she will be using for the event

2. perform an efficient rescue in the event of a capsize of a participant’s paddlecraft, or his/her own paddlecraft

during the event

or has otherwise demonstrated to a recognized paddling professional that he/she has these skills.

The following restrictions apply:

1) If the Level 1 (Paddling + Hiking) Leader is under the age of majority in the Province in which they are leading,

they must be directly supervised by an adult who is also has the LL1 certification or higher. Directly supervised

means that the adult is leading the group and is able to observe or at least be in verbal contact with the minor

throughout the event.

2) If The Level 1 (Paddling + Hiking) Leader is a new leader, they must be directly supervised by an adult who also

has the LL1 certification or higher until a qualified supervisor judges that they have attained the skill, experience,

and judgment to become an equal partner in the leadership team, or leader of the event.

The following extensions apply:

1) The Level 1 (Paddling +Hiking) Leader may lead a group in a higher risk environment where they hold a valid

certificate for the risk factor that makes that environment higher risk. All other risk factors must remain compatible

with the descriptors for Low Risk Water Environments and/or Class 1 Hiking Terrain. For example: the Level 1

(Paddling) Leader with a Paddle Canada Moving Water Instructor certification can lead 1 day trips in a moving

water environment

2) The OCC is unable to vouch for any leader that leads in an environment not covered by the above scope of

practice. However, the OCC recognizes that there are many experienced outdoor leaders who do not have formal

certification for some of the trips they lead. In part this situation exists because accessible, affordable, and

appropriate leadership certification has not been available. Collectively, these people are providing an excellent

service to the community and the majority of them are competent to lead in the environments they do. However,

such leaders should be aware that the most serious incidents occurring to custodial groups have typically happened

to more experienced leaders who did not have certification specific to that environment. The OCC recommends

that such leaders, and their supervisors, take the necessary steps to assure themselves that other recognized outdoor

leaders with equivalent or higher qualifications agree that they have the necessary skill, experience and judgment

to lead the event.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

7

Quiz 1

A person may be qualified to lead an activity even though they are not certified to do

so. You will know that you are qualified to lead an event into environments you are

not certified for when:

a) You have more than 10 years of experience leading and feel you have the

necessary experience.

True False

b) You have 3 years of experience and over 100 days in the field and you have

not had an accident.

True False

c) Other respected outdoor leaders who agree that you have the required skills

and experience.

True False

d) Any of the above.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

True False

8

Chapter 1

Reasons to Become an Outdoor Leader

Outdoor Leadership – What’s in it for me?

There are many reasons why a person might become an outdoor leader, but you may be

surprised to find that what might seem like an exciting bonus for one person can seem

like an unpleasant chore for another. While preferences are natural, we must be careful

that our dislikes don’t result in our failing to do things that will be important for the

quality and safety of our program. We also need to be aware that we may make choices

that might please us, but which are not helpful to the success of our event.

Good Leaders Enjoy their Role

Outdoor leadership should be an enjoyable and rewarding experience. In fact it is

important that it be for two reasons:

1) Leaders who enjoy leading will convey this enthusiasm to their group.

2) Good leadership requires hard work, and it isn’t possible to pour your heart into a

job you don’t like. Being a good leader is only possible if you are getting

something valuable in return.

The requirement to enjoy leadership is not a license to do the things you enjoy and avoid

the bits that you don’t. There are ‘must do’ jobs that leadership requires of you, and it is

your responsibility to do them to the best of your ability. More than this, if you skip

‘must do’ jobs, both the safety and the quality of your event will be compromised. When

that happens, leader satisfaction will drop as well.

Not all Personal Rewards are Legitimate Rewards

There are rewards that you might enjoy, but which you will have to place on the back

burner. If you allow your need to experience these rewards to dominate how you run your

event, you will create an unpleasant, unproductive, or even risky experience for your

group. Here are some classic examples:

Challenge: Getting the level of challenge right is important for everyone, whether it

be physical or mental challenge. Set the challenge too low, and everyone is bored, but

set it too high and learning ceases and the risk goes up. A common leadership mistake

is to set the challenge too high because it seems comfortable to the leader.

Novelty: The advantage of running a similar event in a familiar place is that we can

work the ‘kinks’ out. An event that is new for us will tend to have lower quality and

more risk than an event we are familiar with. However, it can get boring for you to

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

9

run the same event over and over again. There are dangers associated with this

situation too. The bored leader is more likely to miss developing problems through

inattention.

Two things should be used to help with the novelty dilemma. The most important is

that you find the novelty you need within the group. By being people focused, you

will always find novelty as each unique group reacts in a unique way to their day. The

second thing to keep in mind is that you should change your routines and try new

ideas or events. The trick is to limit the number of new things that you introduce for a

particular event to a level that you can safely manage.

Resolving Leader’s and Participant’s Needs

To help you manage this balancing act we suggest that you follow a process that looks

like this:

Step 1): Identify those things that make or might make outdoor leadership

rewarding for you.

Step 2): Divide those ‘rewards’ into four types:

1) Those rewards that could be part of the event itself, but are

incompatible with maximizing the rewards of quality and safety for the

event (e.g. personal thrill-seeking while leading youth).

2) Those rewards that could be part of the event itself and are compatible

with the event (e.g. the pleasure of working in a natural environment).

3) Those rewards that are created by the event and contribute directly to

the quality and safety of the event (e.g. the satisfaction of a job well

done).

4) Those rewards and/or penalties (negative rewards) that are created by

being a leader of the event, but must be balanced with the interests of

the group (e.g. the need for payment, or a need for some personal time).

Step 3): Plan and execute your event so that:

1) Only those types of rewards found in 2), 3) and 4) are satisfied.

2) Use strategies to reinforce the value you place on the type 2) and 3)

rewards. We will cover how to do this in ‘Event Debriefing’.

3) When type 4) rewards are not met it will reduce your ability to lead

well. Try to find the right balance between your interests and your

participants’ interests for the type 4) rewards.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

10

For these reasons it is important for us to think about what we like, or think we would

like, about outdoor activity. To help you do this, please fill in the ‘Motivation and SelfDiscovery’ exercise below.

Motivation and Self-Discovery

(Try to be as honest as you can. There is no right or wrong response)

For each of the things that outdoor leadership could bring, circle how much

you like (or think you would like) each one where:

1 = I don’t like it at all

5 = I am passionate about it

Being outdoors

Learning from others

Physical activity

Working with adults

Working with children

Sharing my knowledge

Being the centre of attention

Role modeling

Challenging social situations

Challenging my physical skills

Working within the policies of my organization

To play a supporting role in a group

The difference I make in the lives of others

The freedom unplanned situations offer

New experiences

Risk taking

Being quiet and alone, or with a few close friends

The respect of others

Being in charge

Other? _______________

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

11

Chapter 2

Pre-Event Planning (The Vision)

Introduction

The odd thing about accidents is that they don’t happen by accident. Often there is a final

decision that triggers the accident, but before that there are typically many other decisions

that lead us step by step to that final decision. This sequence of decisions is called the

‘accident chain’.

Luckily there are ways to break the accident chain before it leads to a problem. By

planning your event in a systematic way, you can create the conditions for a safe event.

Great events don’t happen by accident either. In fact the same good decisions that break

the accident chain will be the building blocks for a great event.

The Vision

Each event starts with some sort of reason or purpose for creating the event. You have a

general idea of what you want but getting from that general idea to a real event and safely

back home will require careful planning. The first stage of that planning is to consolidate

that reason or purpose into a ‘Vision’. The ‘Vision’ stage of planning is critical and

requires you to consider exactly who will be on your event, what activities you will be

doing, and where the event will take place. These three elements will have to work

together if your vision is to become a successful event.

Your Participants

In the previous chapter we looked at our personal reasons for being a leader. We did that

because good leaders meet their own needs by doing a great job of meeting the needs of

their participants. For you to do this, you will have to know something about your

participants. More than that, you will have to anticipate how they will respond to the

event you are planning. These are some of the things you should consider:

-

How new will this experience be for them? To you a day in a Low Risk Natural

Environments may seem very non-threatening, but if your group has little experience

they may be either physically and/or psychologically unprepared for this new

experience. If this is the first event you have had with this group, make sure you find

out what experience they do have. Things to be aware of are:

i) They may exaggerate their experience or ability.

ii) The stress of anticipating the challenges the day offers may exhaust them

much earlier than you ever expected.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

12

iii) They may lack very basic skills like how to properly grip their paddle or how

to recognize that they have sunburn developing.

-

What is the right level of physical challenge for them? There are two components to

physical challenge: technical difficulty and the energy required to complete the

paddle. While paddling on calm flat water is technically easy, it can be surprisingly

challenging for people who have never paddled. It can become even more difficult if

paddling tandem and both partners need to communicate and work together to move

their boat efficiently. This sort of paddling also requires muscles that are rarely used.

Also, many people are psychologically unprepared for the experience of tiredness

while paddling. These factors should be taken into account before the event. The right

level of difficulty is the one that leaves participants feeling that they have met a

challenge, but not so difficult that they never want to paddle again.

-

How do these specific people work together as a group? Every group has its own

internal dynamic. A group of friends that are comfortable and uncompetitive with

each other is easy to lead. A group where people don’t know each other can be more

challenging. The most difficult group to lead is one where there is competition or

dislike between the members of the group. You will typically achieve less with this

group and have more difficulty in managing risk. Plan accordingly!

-

How well do you know the group (and vice versa)? Where you do not know the group

well you will need to make more conservative choices. For this sort of situation it is a

good idea to make a conservative ‘Plan A’ that is suitable for a weaker than average

group. Then, if the group turns out to be stronger than expected you can move to a

more ambitious ‘Plan B’.

-

How well do you know the group in an natural environment? Even if you know the

group well in one environment (such as the classroom), you may be surprised by how

differently they perform in a natural setting. Again, start with a conservative ‘Plan A’,

and only move to ‘Plan B’ if their performance warrants it.

Remember that individuals and groups can vary in their ability to be successful on your

event. If at all possible, consider a training day that will give you some idea of how they

will perform. If your adventure is more ambitious, a more in-depth training program

might be more appropriate.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

13

The Activity

There are many wonderful things that you can do in natural environments, but you cannot

do them all on the same day. As you consider this element of the vision stage your focus

should be to:

1) Identify clearly what the goal(s) or purpose(s) of the event are.

2) Scale the goals to the abilities of the group and nature of the field location.

We know that outdoor activity and education provide many learning and health benefits,

but these benefits do not just ‘happen’. In fact a poorly planned event can have exactly

the opposite effects. Physical injuries do not promote health, and poorly planned or

executed experiential education does not educate. Worse than that, because outdoor

events can be such powerful personal experiences, if they are negative experiences they

can create significant psychological damage to a student’s self-image, or forever

convince them that natural environments are hostile and dangerous places.

Having a clear vision of what the event’s goals are will help you design the best activities

you can to achieve them.

If you identify more than one goal/purpose for the event, you will need to consider how

compatible those goals are with each other. For example, a reasonable goal is to offer a

paddling event that will teach the basics of paddling while providing enough of a workout

that the group will feel a sense of physical achievement. Another reasonable goal is to use

a field day to bring together and provide context for a six-week aquatic ecology program.

However, these two goals cannot be achieved on the same day. Of course, a few elements

of environmental education might enrich a paddling event without detracting from the

main goals, and some preparation regarding the physical demands of an aquatic ecology

field event are essential if the students are to maximize their ecology learning.

The Venue

The venue, or place where the event will happen, is often the place that inspired the

leader initially. This can be an issue. It is very important that your desire to share a place

that is important to you does not encourage you to squeeze either of the other two

elements of a well-constructed vision (participants and activity) into a plan that cannot

work because the venue is wrong for either the activity or the participants. This ‘error’

has been a major contributor to many accidents in the past.

No matter what your goals for the event are, they need to be set at the right level for the

group. That means that they should be challenging enough to engage the attention and

enthusiasm of the group, but no so challenging that they fail to achieve them. The right

venue will support this balance.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

14

Quiz 2

a)

What are the three elements that need to be integrated during the vision stage of

event planning?

1) _______________________________________

2) _______________________________________

3) _______________________________________

b) A poorly planned event can erase the potential educational and health benefits of

outdoor activity.

True False

c) The better you know your participants, the better prepared you will be to plan an

event that meets their needs.

True False

d) Natural environments are really just the venue for your activity, and with a little

creativeness you can make any activity work in any natural environment.

True False

e)

A well-planned event does not need a back-up plan (Plan B). True False

f)

Since outdoor events can be powerful physical and emotional experiences for

your participants, it is important that they be positive experiences.

True False

g) A group that performs well in a classroom setting can be expected to perform

well in an outdoor setting.

True False

h) Having a clear goal or purpose for your event will assist you in choosing an

appropriate activity and venue for it

True False

The Activity Plan

So far we have talked in general terms about evaluating your participants, activity and

venue so that you can make sure that they all fit together. This is a great deal of

information to collect, organize, and compare. It is helpful to do this in an organized way

by creating an ‘activity plan’. This plan contains specific information that will help you

identify a problem if any of your three components don’t fit together. In general, this plan

will be a schedule of what you are going to do and when you are going to do it. This sort

of organizational tool will help you identify any aspect of your vision that is unrealistic.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

15

Typical elements of an activity plan might be:

a) Start & Finish Times: These are the times that will bracket your event and that

everything must fit in between.

b) Total Travel Time: All parts must be accounted for including, vehicle, paddling

and launching.

A standard calculation for paddling time on calm flat water for adults is 15-20

minutes per km without the effect of wind or tides. However, this will depend on

both the age and physical condition of the group. Also remember adding

considerable weight to your boats will slow your group down.

c) ‘Getting Ready to Go’ Organization Time: You will need to allow for some

time to get going at the beginning of the day. This is time is needed by

participants to get themselves ready, and for you to check that everything is

organized.

d) Dry-land Orientation: If this is a paddling event, before you set out on the water

for the day you should take some time to orient your group to the water

environment. This would include things like:

Teaching your group what to do if they end up in the water due to a

capsize.

What their role should be in getting themselves back into their boat.

How you will assist in that kind of situation.

How to safely carry and launch boats and other equipment

Remember your group likely doesn’t spend a lot of time in paddling, so you need

to prepare them for the experience.

e) Contingency Time: You need to set aside some time at the end of the day too,

particularly if it is very important that you finish on time. This will ensure that

small disruptions to your plan do not put the whole event under a time stress that

undermines its success.

f) Specific Activities: If you are incorporating specific activities other than hiking

or paddling into your day you will need to schedule these in too.

g) The Route: Being clear on the details of your route is critical. Obviously you

cannot match the venue to the participants and activity if you are not. Knowing

your route allows you to calculate travel time and to strategize for things such as

where you want to conduct non-travel activities, including food and water breaks.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

16

h) Lunch Spots: While you must always be ready to adjust your plans, it will not

only help you plan your day if you know where you will stop for lunch, it will

also help your participants manage their day and their own comfort if they know

in advance when and where key activities will take place.

i) Decision Points: Few events go exactly to plan, and it is wise to consider in

advance what might be a key clue that a major change is required. For many

routes this will include a ‘decision point’ such as turn-around time, or a point that

you must have reached by a certain time if you are going to be able to complete

your event

j) Plan B: You should consider in advance if there are any things that might cause

you to change your activity entirely. The most common would be adverse

weather. If such a change is required you need to know what you are going to do

with your participants for the time they will be with you.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

17

Chapter 3

Criteria for a Low Risk Environment

Complexity and Quality

Complex challenges can be fun and exciting, but they also come hand in hand with

unexpected outcomes. In natural environments, ‘unexpected outcomes’ usually disrupt

our program and increase our risk. Neither of these will help us build our quality event.

Leadership itself is complex and challenging. Although this course will help you prepare

for this role and accelerate your learning, experience will be the key ingredient that

enables you to put all the ideas in this course into a seamless performance. The beginning

leader would be wise to concentrate on learning to manage the complexities that come

with leadership before exposing themselves to the complexities that more ambitious

paddling offers.

As your skill and experience increase, both as a leader and as a backcountry traveler, you

will find that your ability to understand complex natural environments increases. The

time will come when you can provide a leadership performance that you can be proud of

in complex paddling.

One of the issues that makes complex paddling hazardous is that many of the hazards are

not obvious. The inexperienced leader simply doesn’t ‘see’ that they are stumbling into a

hazardous situation. A number of high profile and very serious accidents have happened

to leaders who simply had no idea that they were in over their heads until it was too late.

For this reason, leaders need to have very specific guidance as to what water

environments are safe for them to use for their events. To assist with this the OCC has

developed criteria for a ‘Low Risk Water Environment’ and ‘Class 1 Hiking Terrain’.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

18

A) The ‘Low Risk Water Environment’

About the Criteria

The general term ‘Water Environment’ describes an enormous variety of natural

environments. Some of these environments are very safe places to be, others are complex

and hazardous. To understand the criteria for a Low Risk Water Environment you will

need to be clear as to what the OCC means by the following terms:

Water Environment:

Is any natural environment that is:

a) Water as opposed to land, and

b) Is not in a winter condition. That is, snow and ice

are absent except in a few small patches that pose

little risk to paddlers.

A Natural Environment: Is any outdoor environment that is not dominated by

manmade structures. This includes both man-made body and

naturally occurring bodies of water.

Now that we have defined what sort of environment we are talking about, we need to

consider the type of complexities or ‘factors’ in that environment that we know have

historically resulted in a source of risk for youth groups. For this course we will restrict

our comments to Low Risk Paddling. The ‘risk factors’ are:

a) Distance to Additional Resources. Most common paddling emergencies can be

easily managed with the assistance of a warm dry place and some addition resources

such as dry clothing or hot drinks and transport to a medical facility. These resources

should be close enough to be accessed within one hour of an event.

b) Access to Shore. Land is a relatively safe environment compared to water. For many

of the common hazards threatening paddlers are best managed by leaving the water.

Note that ‘15 minutes from shore’ means 15 minutes from a shore where you can

quickly and safety get your group off the water. Beaches, boat launches or docks

would all be examples of ‘accessible’ shore where you can get your group on land

and out of a water-based hazard.

c) Current. Currents are powerful water forces that can carry boats and swimmers great

distances, especially if the paddlers don’t understand how or have the skills to

navigate their boats in the current. Travelling with boats in anything but light currents

requires further training and experience than is covered in the LL1 (Paddling)

program.

d) Other Boat Traffic. On many bodies of water in Canada paddlers are not the only

water users, and must share with motorized boats. Since motorized watercraft can

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

19

travel very fast and turn quickly they can cause significant injuries to participants in a

collision. The aim in Low Risk Paddling is to reduce your exposure to the fastest,

least predictable boats by staying close to the shoreline and in shallower water, where

these users usually must slow down and exert more caution.

e) Wind Exposure. Large bodies of water often have significant wind action because

there is no topography to slow the wind down. Strong winds can easily overwhelm

smaller boats under the control of novice paddlers. Wind can also carry paddlers and

boats very quickly in an undesired direction, or turn wet paddlers into hypothermic

paddlers. Strong winds can also create dangerous wave conditions.

f) Wave Exposure. Waves can create some of the most difficult challenges for novice

paddlers. Waves can overwhelm paddlers physically and mentally and also cause

boats to capsize. Paddling with waves capable of capsizing the boats you are using is

beyond the scope of the LL1 (Paddling) program.

g) Navigation. When the shore is in close proximity during your whole event,

navigational decisions are easily made using a technique called “hand-railing”. When

sight of the shore, or good definition on the shore is lost, navigational decisions

become harder and require additional skills and experience with a map, chart,

compass and/or GPS, which is beyond the scope of the LL1 (Paddling) program.

h) Visibility. Navigation and Group Management on the water are both easier when

visibility is good. Fog or other weather can reduce visibility and disorient you as a

leader. Low or poor visibility situations require special training and techniques to

manage safely and are beyond the scope of this course.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

20

OCC Criteria for a Low Risk Water Environment

Risk Factor

Low Risk

Distance to Additional

Resources at Road or Lodge

No more than 1 hr. to a warm dry place

and transport to a medical facility.

Access to Shore

All group members can exit to shore

quickly, easily and safely within 15

minutes.

Current

Currents less than 0.5 knots or 1 km/hr.

Other Boat Traffic

Within the activity area: No boats

traveling faster than 5 knots or 10

km/hr. and other boats not impacting

group management.

Wind Exposure

Prevailing winds greater than 10 knots

or 20 km/hr. are onshore. No wind

speeds exceed 20 knots or 40 km/hr.

Wave Exposure

Waves too small to capsize the least

stable vessel in use.

Navigation

Visibility

Destination is visible and/or shore handline can be followed.

Visibility allows for navigation without

map and compass and doesn’t

complicate group management

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

21

B) The OCC Hiking Terrain Matrix

About the Matrix

The general term ‘Hiking Terrain’ describes an enormous variety of natural

environments. Some of these environments are very safe places to be; others are complex

and hazardous. The ‘Hiking Terrain Matrix’ has been created by the OCC through the

expertise of highly experienced panel members that used defined criteria to divide hiking

terrain into three ‘classes’. To use and understand the Matrix you will need to be clear

about what the OCC means by the following terms:

Hiking Terrain:

Is any natural environment that is:

c) Land as opposed to water, and

d) Is not in a winter condition. That is, snow and ice

are absent except in a few small patches that are

either avoidable or flat.

A Natural Environment: Is any outdoor environment that is not dominated by

manmade structures. This could include a large public garden

or a small urban park.

Now that we have defined what sort of environment we are talking about, we need to

consider the type of complexities or ‘factors’ in that environment that we know have

historically resulted in a source of risk for youth groups. For this course we will restrict

our comments to ‘Class 1 Hiking Terrain’. The ‘risk factors’ are:

i) Distance to Additional Resources. When you set out on a hike you have a finite set

of resources like food, clothing and personal energy. If something does go wrong, the

length of time it takes to get additional resources can affect how serious things

become. For example, getting wet in a rainstorm is not usually serious unless you are

wet for so long that you get hypothermia. So ‘additional resources’ in the matrix

include things like shelter, transport, and additional clothing or food.

j) Fall Exposure. A person can trip on their shoelaces, fall, and hurt themselves, but

this is not the type of ‘fall exposure’ we are talking about. For the matrix ‘fall

exposure’ is any drop that is high enough that a participant could not step down in

slow motion without using their hands. ‘Easily managed or avoided’ means that you

can either walk around it (at a safe distance for larger drops), or it is guarded by a

sturdy rail or fence. Also acceptable would be a single step down that could be

managed easily with a helping hand.

k) Technical Difficulty. Since this is ‘hiking’ terrain, technical difficulty refers to how

hard it is to walk confidently in the coordinated and balanced way we expect to see on

pavement. We expect trails to be rougher than pavement, but when the ground is

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

22

slippery, is covered in small rocks that roll under your feet, larger rocks that you can

slip between, or is quite sloped, we consider this to be ‘unstable footing’. Unstable

footing is tiring to walk on and easy to fall on. Most groups can manage a short

section of unstable footing with the use of extra energy and extra concentration.

When these sections become longer, energy gets used up, concentration wanes, and

so the chance of an accident increases significantly.

l) Fresh Water. Open water is a major source of risk in natural environments. It may

even be the greatest source of risk. Class 1 terrain tries to exclude the possibility of

drowning by excluding still and slow moving water deep enough to drown in and

flowing water that can sweep you away.

m) Tidal Water. The intertidal zone and places close to it can be very hazardous and the

danger is often very hard for the inexperienced person to see. Only those places

where there is no surge, where rising tides cannot cut you off from safe terrain, and

there is no possibility of a slip into the ocean, are included in Class 1 terrain.

n) Weather Exposure. Weather is a highly unpredictable factor that can seriously

impact your event. We will discuss protecting ourselves against weather in the next

chapter, but even with this protection, prolonged exposure to a storm can have serious

consequences. In particular, if we get wet, we may get cold. If it is windy we will get

colder faster. Thunderstorms expose us to the possibility of lightning strikes. We can

reduce the impacts of bad weather by retreating out of the wind and away from the

places most likely to be hit by lightning.

o) Navigation. Getting lost has many potentially serious consequences including the

possibility that you may stray into more complex and dangerous terrain. ‘Staying

found’ can require having a high level of navigational ability. However, in Class 1

terrain, a simple trail/site map will be sufficient for you to find your trail/position.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

23

The Hiking Terrain Matrix

(Note: Definitions for Class 2 and 3 terrain are provisional

and are only included for reference)

Risk Factor

Distance to

additional

resources at

road or lodge

Class 1

Class 2

Class 3

No more than 3 hrs to

trailhead.

Multiple days, but 8 hrs.

hike to base.

No Limit.

Fall Exposure

Easily managed or

avoidable.

Fall hazard exists but

manageable with

moderate consequence.

Short sections with

unavoidable & serious

consequence, but can be

managed without a rope.

Technical

Difficulty

Smooth & Easy.

Sections of unstable

footing are short &

isolated.

Talus and loose footing,

some rough sections,

trails may be poorly

maintained.

Use of hands may be

required. Fixed hand

lines or chains may be

present. May be

sustained sections of

unstable footing.

Fresh Water

25cm deep for

stationary/slow moving

and 15cm for fast

moving with no downwater hazards.

25-50cm deep for slow

moving and 15-30cm for

fast moving with no

down-water hazards.

50cm+ deep for slow

moving and 30cm+ for

fast moving with downwater hazards.

Tidal Water

Gently sloping and nonslippery intertidal zone.

No surge.

Surge channels and tidal

entrapment easily

avoided. Moderate wave

hazard may exist.

Moderately sloping. Some

slipping hazard.

Surge channels, tidal

entrapment and wave

hazards may be present.

Steeply sloping, rocky,

and slippery intertidal

zone.

Weather

Exposure

Generally sheltered, or

easy retreat to shelter.

May be exposed but can

retreat to shelter within 45

minutes.

Exposed areas with

difficult or no retreat.

Navigation

On trails, or untracked

with natural boundaries

and/or handrails.

Simple route choices.

May require a compass

and/or GPS.

Complicated navigation,

difficult route finding or

minimal landmarks.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

24

Chapter 4

Pre-Event Planning (Hazards and Defenses)

Compared to many other sports paddling in a Low Risk Water Environment or hiking in

Class 1 Hiking terrain are low risk activities, but there are still risks. As leaders, it is our

responsibility to anticipate these risks as best we can, and take appropriate measures to

reduce them to an acceptable level. This chapter will talk about some of the principles

and techniques used in this process.

Hazard and Mitigation Factors

A hazard is anything that might give rise to a negative consequence for our group. Wind

is a typical summer hazard. There could be many consequences of being caught in a

strong wind event. This could range from increased physical exertion to move the boats,

to life-threatening hypothermia, loss of effective communication between paddlers,

capsized boats, etc.

A hazard defense is anything that reduces the consequence to our group if we become

involved with the hazard, or prevents us from being exposed to the hazard at all. Boat

control skills are a defense that helps reduce the risk of capsizing. Staying close to shore

is a defense that reduces the hypothermia hazard associated with capsizing.

Vulnerability and Resilience

Our vulnerability is the degree to which we can be affected by a hazard. For instance,

children are typically more vulnerable to hypothermia when they get wet after capsizing

than are adults.

Our resilience is our ability to respond to unexpected adversity in ways that reduce the

consequences of that adverse situation. In many ways resilience is just the opposite of

vulnerability. For example, a person with rain gear is more resilient to the consequences

of rain than a person without rain gear.

Since the risk of being adversely affected by any one of a multitude of hazards during our

event can never be reduced to zero, a key risk-reduction strategy is to identify potential

hazards, recognize our level of vulnerability to those hazards, and plan so that we can

increase our resilience to them.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

25

Good Planning Creates Resilience

Choosing a lee-side water environment on a windy day not only increases our resilience

to capsizing, but it also increases our groups’ resilience to psychological harm that might

result from a cold and exhausting day out in the full force of the wind. A good defense

adds to our resilience in unexpected ways. Since accidents happen when the unexpected

happens, the group that has a network of good defenses will be more resilient to the

unexpected. A well planned, appropriately equipped, and well led event leads to a

resilient group that has an excellent chance of surviving the unexpected without harm.

Measuring Risk

Every accident that ever happened could have been avoided had people made different

decisions. That doesn’t necessarily mean that the people who had those accidents were

foolish. We experience risk because we are not able to predict all possible outcomes from

our decisions, and sometimes things do not work out as we hoped they would. Accidents

can and do happen to everyone.

While accidents can and do happen to everyone, we can plan to reduce risk. It is useful to

know that there is a standard way of measuring risk:

The Size of a Risk = Probability (of the event) x Consequence (of the event)

We can reduce risk by either reducing the probability of something going wrong, or by

reducing the consequences if it does go wrong. For example, we can reduce the

probability of being involved in a bad rainstorm by reading the weather forecast and

canceling our event if it looks like it is going to rain hard. If we decide the weather looks

good enough to go and the weather forecast is wrong, we can reduce the consequences by

having good rain gear.

Reducing Risk by Reducing Complexity

As we have already mentioned, risk occurs because we cannot possibly predict all

possible outcomes from our decisions.

However, the more skilled and experienced we are in a particular environment, the better

able we are to predict outcomes, and so we become better at reducing the chance of a

serious mistake. On the other hand the more complex the environment, the harder it is to

predict outcomes, and the more skill and experience we need to lead an event there.

This course is designed to train you to the degree that you will be able to lead a youth

group into a Low Risk Water Environment or into Class 1 Hiking Terrain. This

environment has been defined so that:

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

26

-

Many types of natural hazards don’t exist there – so you don’t need any

specialized training to manage them.

-

Where a natural hazard exists, the Leadership Level 1 Leader should be able to

predict and/or manage it well.

-

If an unforeseen event occurs, the Leadership Level 1 Leader will still have a

good chance of managing things so as to keep the long-term consequences small.

If you go into more complex water and/or hiking environments, without additional

training and experience that has been validated as sufficient by other respected outdoor

leaders, then there is a good chance that you are exposing your group to an unacceptable

level of risk.

Reducing Risk by Recognizing the Hazards and Building Resiliency to Them

Risk will be our constant companion, not just on our events, but also throughout our

endeavours. Our job for the hazard management part of event planning is to navigate the

path through a 4-step process:

1) Correctly identify the likely hazards – what things might go wrong?

2) Correctly assess our vulnerability to those hazards, i.e. what will the possible

consequence be for us if something happens?

3) Correctly identify the appropriate defenses that will either help us avoid those

hazards, and/or build our resilience to them.

4) Plan and prepare accordingly.

An Important Note about the Nature of Risk

Before we begin the process of hazard management, we need to be clear that this process

is not about reducing risk to zero. That is not possible.

If risk can’t be eliminated, one might think that the right course of action is to do

whatever it takes to reduce the risk to a minimum, but that isn’t correct either. Every

defense we build carries costs. These costs will be things like the planning effort

required, the financial cost, the cost of too heavy a boat full of gear, etc. Eventually,

adding too many defenses will make our event impossible and then it can never deliver

the benefits it was run for in the first place.

Our goal is to match the defenses to the risk the hazard presents. Where the risk is

greater, you need better defenses, but where it is less you need fewer defenses. If the risk

is very small you may need no special provisions at all.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

27

Quiz 4a)

a) Good planning will eliminate risk.

True False

b) If a risk exists you should make every effort to prevent it from impacting your

event.

True False

c) You should try to match the size of your defense to the size of the risk.

True False

d) Many types of hazards do not exist in Low Risk Water Environments and Class 1

Hiking Terrain, so you do not need to include risk management in your event

planning.

True False

e) What two factors are considered when measuring the size of a risk?

1. ___________________________

2. ____________________________

Low Risk Natural Environments Hazards

Low Risk Natural Environments are places where the sorts of accidents that result in

serious injury or death are extremely rare. However, ‘minor’ physical and psychological

injuries are quite common. As these injuries are ‘minor’, it is easy to discount them, but

collectively these ‘minor’ issues are a big deal for two reasons:

1) The risk equation tells us that risk = probability x consequence. This means that if

minor injuries are common, then even though the consequence of each one is

small, the risk may be quite high.

2) When we talk about risk in natural environments we tend to focus on physical

risk. This is because physical injuries are ‘in your face’ since they are easy to see

and measure, they create paperwork, and are more likely to result in a lawsuit. As

leaders we need to be equally concerned about psychological injury. You will

never be sued for giving a participant such a horrible experience that they resolve

to never go paddling and/or hiking again. You may not even know that your event

has had such a profoundly negative effect on their life, but this sort of injury is

common, serious, and mostly avoidable though good planning and leadership.

As we prepare to identify and defend against hazards, it is useful to think about hazards

as being grouped into two types: those that originate in the environment, and those that

originate in the person.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

28

Environmental Hazards - Introduction

Although Low Risk Natural Environments are comparatively relatively safe places, there

are still environmental hazards that need to be managed. These include weather effects,

wild animals, and physical injury.

Low Risk Natural Environments are very different environments. The way in which

environmental hazards interact with these two environments to create a threat to your

group also varies. For example, a moderate wind may present no great threat to a hiking

group but may create dangerous conditions for a paddling group.

In particular, note that Class 1 Hiking terrain has very stringent restrictions on water

depth. This is because water that is deep enough to drown in can be a real hazard for the

unprepared hiker. Deep water is manageable on a paddling trip because appropriate

defenses are employed.

The Paddling Leader encounters the interface between hiking terrain and deep water

every day and needs to be careful to ensure that everyone in the group is in paddling

mode when in that transition zone.

Water Hazards

Water can be a very unforgiving medium, and water environments can change their

character very quickly. This is why the restrictions on flat and flowing water are so

stringent for Class 1 Hiking Terrain. However, the Paddling Leader must engage water

directly and so needs to be aware of and alert for water hazards and how they may affect

the group.

a) Drowning: This is the most serious hazard that you will face in water environments.

If we use the risk equation, the consequence is extremely high so if even if the

probability is small, the risk is still significant. This risk can be reduced to near zero

by ensuring that every member of the group, including you is wearing a properly

fitted and approved Personal Flotation Device (PFD). Many water environments

appear quite benign, but many have drowned in situations where the threat appeared

to be very remote. Factors to consider include:

- When immersed in cold water, people lose their ability to defend themselves very

quickly. Being a strong swimmer does not help, and in fact the fit person can

actually succumb to hypothermia more quickly than an overweight person.

- While a trained person can put on their PFD after they have fallen in the water

when the water is warm, cold water can make this impossible within a few

minutes.

- If a participant falls into the water, either off the shore or out of a paddle craft

there is the possibility of a head injury that could leave them unconscious. If they

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

29

-

are not wearing a PFD they will not stay floating very long and could drown

extremely fast.

If a person panics they can drown even in standing height water. Even strong

swimmers can panic if they are psychologically overwhelmed by the situation.

Any situation where a head injury is possible could lead to a person drowning if

they lose consciousness.

The young are particularly vulnerable. Being shorter they get ‘in over their heads’

more easily; they are more likely to panic; and they are less likely to realize a

dangerous situation is evolving.

Because of these complications, the OCC recommends that everyone should wear a

PFD in any situation where drowning is possible unless the following situations

apply:

i.

An activity, such as swimming, does not permit wearing a PFD. In which case

a protocol similar to the OCC ‘Non-PFD Water Access Procedures’ should be

in place (Appendix E)

ii.

An activity can be conducted while wearing a PFD, but is significantly

compromised by wearing one. In this case the ‘OCC PFD Protocol’

(Appendix F) should be consulted to discover if the PFD may be not worn.

Finally, all major waterways and the ocean are under federal jurisdiction and the

Federal Government requires that every vessel be equipped with a PFD for every

passenger. While this law does not apply to water bodies under municipal, provincial

or private jurisdiction, it only makes sense to follow the same policy.

b) Wet Gear and Clothing: In the event of a capsize, it is possible to get all of your

equipment soaking wet. If the weather is nice and hot, and being wet to cool off isn’t

a problem, then this is not serious. But if the weather is cold, windy and rainy and a

participant capsizes then you need things like warm dry spare clothes, emergency

shelter, first aid kit and fire starters. As a leader, make sure that your own gear, the

group emergency gear and your groups’ dry spare change of clothes are waterproofed

in some fashion for the duration of your activity on the water, and that that gear stays

dry. Wet and Dry suits also increase your groups resilience. They increase the time

that you need to get everyone to shore and back into dry clothes.

c) Submerged Hazards: Things like dead trees (dead heads) or submerged man-made

structures can pose a variety of hazards to your group, but in general, a participant

hitting one of them with their boat could mean anything from a damaged boat to a

capsize. You will need to spend some time teaching your participants how to identify

and avoid these types of hazards.

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

30

Shore Hazards

Because of the seriousness of drowning and/or hypothermia it is easy to overlook the

hazards that the shore itself can present. This transition between land and water could

have features that make it easy for an injury to occur. These features include steeply

sloping surfaces, short drops, slippery/vegetated surfaces, and sharp rocks. The chance of

injury can increase by having to carry boats or other equipment through this transition

space. These hazards can be mitigated by:

a) Choosing put-ins/pull-outs that are easy for people to navigate.

b) Making a plan as to how you will manage the group during the transition to

and/or from the water, and make sure everyone knows what the plan is.

c) Reminding/alerting your group about the specific hazards that the environment

presents.

d) Making sure there are enough people to manage awkward or heavy loads, and that

they know how to work as a team. Each person should be briefed on how to avoid

injury in this scenario.

e) Considering having yourself or another person remain detached from any work so

that they can monitor progress and intervene if an unsafe situation starts to

develop.

f) Having people wear protective equipment (such as gloves, lugged shoes, long

pants, etc.) for particularly difficult transition areas.

Weather Hazards

Historically, weather has been a major factor in most serious accidents that have

happened in natural areas. Weather can cause serious injury or death even in Low Risk

Natural Environments. We can defend ourselves from weather in two ways: we can avoid

extreme weather by canceling our event or turning back early and/or we can take

equipment that protects us against the effects of strong weather.

Major weather factors to consider are:

a) Rain: Rain can be a hazard to both paddlers and hikers because it can result in people

getting wet and cold. Rain is often accompanied by wind and colder weather, which

are the perfect ingredients for hypothermia. Rain also makes trails and rocky shores

slippery, and reduces visibility particularly in paddling environments. When planning

for rain, consider the following:

- Remember that weather forecasts are not completely reliable predictors of the

possibility or severity of rain. For that reason, you must plan for a severe

rainstorm, even if one appears to be unlikely.

- Consider cancelling an event if the forecast indicates that there will be enough

rain to result in people getting seriously wet and cold. The level at which this call

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

31

-

-

-

-

will be made should take into account the vulnerability of the group. Vulnerability

is influenced by the age of the participants, the quality of their rain gear, and their

level of experience with natural environments.

You can defend against rain by making sure everyone has appropriate rain gear.

The quality of this gear will influence how much protection your group gets. For

this reason, you will need to take this into account when planning your event.

Where your event will take you further from a warm dry environment, quality rain

gear for everyone is absolutely essential.

The quality of the rest of a person’s clothing is also a factor. In particular, if

participants are wearing cotton, they are very vulnerable to rain. Even good rain

gear will not keep the water out completely, so for events that take you further

from a warm, dry environment you will need to consider how effectively the

participants' clothing will keep them warm once it is wet.

If your event takes place very close to a warm, dry environment, then rain gear

may not be essential, but that will mean that your event may have to be cancelled

or cut short if it rains.

Since rain can make trails, and put-ins and pull-outs slick – good footwear is an

essential. Ideally this footwear should be close-toed and provide warmth for the

feet (i.e. neoprene for paddlers), but at the very least it should have a lugged sole

that will grip on slimy and muddy surfaces.

b) Cold and Hypothermia: The Leadership Level 1 (Paddling + Hiking) course will

prepare you for land and water-based activities in natural environments providing the

temperatures are relatively warm. Additional training is required for winter events.

However, even in mid-summer, the weather can be cold in Canada, and rain or wind

will only worsen this cold. Obviously, everyone in your group needs to have

sufficient clothing to protect against the cold. This may include a hat, gloves and an

extra warm layer.

If it looks like your event will take place in cool or cold weather, you also need to

make sure that everyone brings extra clothing. Typically people bring enough clothes

to keep warm while moving, but if you have to stop for a long time they will quickly

become cold. You may not be planning to have such a long stop, but you need to be

prepared anyway just in case you have a medical emergency that immobilizes one of

the group.

In Low Risk Water Environments the chance of participants getting cold is increased

by the possibility that they might get wet either intentionally or unintentionally during

the course of the activity. When people get cold they become more vulnerable to

other hazards and they may also become hypothermic. Hypothermia is a serious

condition that can result in death. Beyond warm clothing, the following points should

be taken into account regarding defenses against cold and hypothermia:

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

32

-

-

-

-

If your activity plan includes participants swimming or otherwise getting wet in

colder weather everyone needs to have clothing and equipment (i.e. neoprene

wetsuits) that will allow them to regulate their body temperature during the

activity. In general it is never a good idea to plan for a group to spend much time

in cold water, or in the water in cold weather. Have a plan for how you will get

the group warm and dry after the activity has finished.

If your activity plan does not include getting wet, you still need to make sure you

have the ability to evacuate your group to a warm dry place quickly in the event

they get wet anyway.

Wet or Dry suits maybe appropriate to prevent Immersion Hypothermia if a

participant might have the possibility of ending up in the water.

Immersion Hypothermia starts at an air temperature plus water temperature of

colder than 38 degrees Celsius. Immersion Hypothermia, like land-based

hypothermia can be mild or severe. In severe hypothermia the person must be

evacuated to a hospital.

Mild immersion hypothermia - less than 20 minutes in still water

less than 7 minutes in moving water

Severe immersion hypothermia - more than 20 minutes in still water

more than 7 minutes in moving water1

It is important to evacuate the person if they have experienced the potential for

severe hypothermia even if they look “okay” They could be at risk for severe

complications.

c) Wind: Wind can be a powerful force. Wind not only wicks away heat but can also be

very tiring and confusing for your participants. Where strong winds are mixed with

cold or rain, as they often are, they can create a very challenging environment. Issues

with this sort of environment include:

- Wind cools participants quickly

- Hiking in an overpowering wind is very tiring.

- Strong winds can topple trees or blow down branches creating dangerous

situations for your group

- On water strong winds can:

Carry boats long distances in a relatively short amount of time and/or make it

impossible for people to steer their boats effectively. Under these conditions

participants can quickly become exhausted and your group could end up

dangerously far from shore, driven onto a dangerous shoreline, or into busy

boat traffic lanes.

1

From: Anna Christensen. Beyond help: Explorer First Aid. (2008).

Leadership Level 1 (Paddling) ©

Outdoor Council of Canada / Conseil canadien de plein air

33

Cause boats to capsize by blowing them over or by creating large and/or

choppy waves.

Make it difficult for the group to stay together and may reduce your ability to

communicate with your group. Teaching paddle signals to your group and

using them can be a good defense against loss of communication on the water.

Defenses include:

- A windproof outer shell and clothing

- On land, trees will provide shelter but not during extreme winds. Consider

canceling a hiking event if exceptionally strong winds are forecast.

- Choosing a venue where you will be protected from the wind or, on water, where

the expected winds tend to push you toward a safe shore.

- Consider canceling the event if strong winds are forecast.

- Becoming knowledgeable about what sort of weather creates dangerous winds in

your area.

- Monitoring the weather continuously, even on good weather days.

d) Thunderstorms: Thunderstorms can happen at any time of the day, but are usually

an afternoon and evening phenomenon. They are also quite unpredictable, so even if

the weather forecast does not mention thunderstorms, you should be alert to the

possibility that you may encounter them. Since heavy rain and wind are features of

thunderstorms, our defenses include good rain and wind equipment. However, a

lightning strike is a particularly dangerous feature of thunderstorms. Lightning kills

Canadians every year. Fortunately, we can defend ourselves against lightning strikes

by recognizing and avoiding high-risk areas. In general, the electricity in lightning is

seeking the shortest route between the ground and the sky so:

On Land:

- Avoid ridge crests and especially small summits on ridge crests.