Movement in Art: Visual Design Principles

advertisement

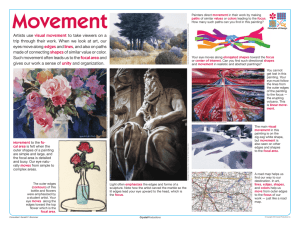

Movement Used by artists to direct viewers through their work, often to the focal area. Such movement can be directed along the lines and edges; also by way of spaces and colors within the works. Movement is directed most easily on paths of equal value. What does movement do? • Artists use visual movement to take viewers on a trip through their work. When we look at art, our eyes move along edges and lines, and also on paths made of connecting shapes of similar color or value. Such movement often leads us to the focal area and gives our work a sense of unity and organization. Moving along edged (contours) • The outer edges (contours) of the bottle and flowers were emphasized by a student artist. Your eye moves along the edges toward the top flower which is the focal area. Movement in Sculpture – 3D • Light often emphasizes the edges and forms of a sculpture. Note how Michelangelo carved the marble to the lit edges lead your eye upward to the head of Moses, which is the focus. Your eyes follow shapes toward the center of focus, or focal point. • Your eye moves along elongated shapes toward the focus or center of interest. • Do you think you can find such directional shapes and movement in realistic and abstract paintings? • Painters direct movement in their work by making paths of similar values or colors, leading to the focus. • How many such paths can you find in Mendocino Morning, by Gerald Brommer? Value Paths Create movement to focal points • Movement is created in the painting on the left as your eye travels from the little girl on the blanket and moves up the stairs. The light value paths of the blanket & the wall behind the girl on the stairs is repeated. Our eyes move back and forth from these two areas, leading us to the focal points of the image, which are the girls on the blanket, as well as the girl going up the stairs. Lines and Linear Movement • You cannot get lost in this painting. Your eye must follow the lines from the outer edges of the painting to the focus – the erupting volcano. This is called linear movement. Lines, Edges, Shapes & Colors Lead us through artwork • A road map helps us find our way to our destination. In art, lines, edges, shapes, and colors help us move from outer edges to the focus of our work – just like a road map. Large Shapes lead us to Detailed Focal Area • Movement to the focal area is felt when the outer shapes of a painting are simple and large, and the focal area is detailed and busy. Our eye naturally moves from simple to complex areas. Visual Movement with shapes • The main visual movement in this painting is on the zigzag white shape, but movement is also seen on other edges and shapes to the focal area. Using Repetition to Create Movement • The use of repetition to create movement occurs when elements which have something in common are repeated regularly or irregularly sometimes creating a visual rhythm. Repetition doesn’t have to be exact to create movement. • Repetition doesn't always mean exact duplication either, but it does mean similarity or near-likeness. Actually, slight variations to a simple repetition will add interest. Repetition tends to tie things together whether they are touching or not and is an easy way to achieve unity. This can be done with any of the elements of art (form, line, shape, value, texture or color). Effective Use of Repetition to Create Movement • Repetition creates the movement in the painting on the left. The color of the gowns is repeated leading the eye into the painting. The pattern on the floor also creates repetition. Using Rhythm to create movement • Rhythm is the result of repetition which leads the eye from one area to another in direct, flowing, or staccato movement. • It can be produced by continuous repetition, by periodic repetition, or by regular alternation of one of more forms or lines. A single form may be slightly changed with each repetition or be repeated with periodic changes in size, color, texture, or value. A line may regularly vary in length, weight, or direction. Color may also be repeated in various parts of the composition in order to unify the various areas of the painting. Using Action to create movement • Movement can also be created by action. In two• • • dimensional works of art, action must be implied. Implied action in a painting creates life and activity within the composition. This is best illustrated by the direction the eye takes along an invisible path, which is called implied line, created by an arrow, a gaze, or a pointing finger. Action can also be indicated by the "freeze frame" effect of an object in motion, such as bouncing ball suspended in mid air, a jogger about to take that next step, or a swimmer taking a dive, etc. Using Optical Movement • Optical Movement can also be used in a work of art. Artists such as Bridget Riley and Victor Vasarely used shape, color and line to create a physical sense of movement in works of art. This period of art is often times referred to as The Op Art Movement. Optical movement produces a disorienting physical effect on the eye. Summary: make sure this information is on your journal pages. • • 1. Definition of Movement: used by artists to direct viewers through their work, often to a focal point. Such movement can be directed along the lines and edges: also by way of shapes and colors within the work. Movement is directed most easily on paths of equal value. • 2. The purpose of movement is to create unity in artwork with eye travel. • 3. Movement in a work of art often leads us to the focal area and gives the work a sense of unity and organization. Movement can be achieved in art by using: • 1. Repetition – elements which have something in common are repeated in a work of art • Rhythm - produced by continuous repetition, by periodic repetition, or by regular alternation of one of more forms or lines which leads the eye from one area to another in direct, flowing, or staccato movement (abrupt changes in forms or lines) • 1. In Art Staccato refers to: detached, short and disconnected, often using shapes, lines or forms • 2. Action - In two-dimensional works of art, action must be implied. The direction the eye takes along an invisible path created by an arrow, a gaze, or a pointing finger. Action can also be indicated by the "freeze frame" effect of an object in motion • 3. Linear movement – the eye travels along a line path. The line can be either solid, broken or implied. • 1. Implied Line: A line that is visually suggested by the arrangement of forms, lights and darks, or other elements in a work of art. An implied line is not actually there, but leads the eye from one shape or form to another. (An example might be, if a person were pointing in a certain direction, you would look in that direction) • 2. Size Paths – the eye follows larger elements to smaller elements • 3. Value Paths – The eye follows dark elements to lighter elements • 4. Color Paths – From colored areas to non colored areas, or changes in color values (light colors to darker colors) • Shape Paths – The eye follows unusual shapes to usual shapes, or larger shapes to smaller shapes • 1. Our Eyes naturally move from simple to complex areas of a piece of artwork. • 2. Light Often Emphasizes the edges and forms of a three dimensional sculpture. • 3. Optical Movement is another way to create movement in a work of art. Using shapes, color and line to create a physical sense of movement in works of art. This period of art is often times referred to as The Op Art Movement. Optical movement produces a disorienting physical effect on the eye. Activity: Classroom • Movement can be seen in the following artwork. Choose from the following list, or from your own observations, elements the artist may have used to create movement in their work. Write at LEAST 4 things about movement within each piece. Be specific in your answers. • Work with one partner. Follow the paths of movement in each and write down, in order what you see. Compare your answers with your partner. Use the following words where appropriate when describing the slides • • • • • Repetition Rhythm Action Lines/Linear Texture • • • • • Size Value Color Shape/Form Optical Movement Example: In the first work, Juggling Man, you might list: • 1. It is a three dimensional sculpture • 2. Light allows our eyes to see shapes and forms. • 3. Our eyes follow value paths to the focal point which is the face. We look at the lighter areas first, and then follow the linear contour lines of the arms and legs until we come to the face. • Because the arms are outstretched, creating linear movement, our eyes keep moving along them, bringing us back and forth to see what he has in his hands. 1 Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Spanish, 1746-1828), The Forge, between c. 1815 and 1820, oil on canvas, 71 1/2 x 49 1/4 inches (181.6 x 125.1 cm), Frick Collection, NY. • 1. • 2 • 3 • 4 2 Eadweard Muybridge, Jumping a hurdle; saddle; bay horse Daisy Plate 640 of Animal Locomotion, 1887, collotype, Worcester Art Museum, MA. • 1. • 2. • 3. • 4. 3 Winslow Homer (American, 1836-1910), Snap the Whip, 1872, oil on canvas, 12 x 20 inches, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. • 1. • 2. • 3. • 4. 4 Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853-1890), The Starry Night, June 1889 (Saint-Rémy), oil on canvas, 29 x 36 1/4 inches (72 x 92 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York, F 612 • 1. • 2. • 3. • 4. Georges Seurat (French, 1859-1891), The Circus, 1891, oil on canvas, 73 x 59 1/8 inches, Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Georges Seurat used pointillism to create this painting. Dots of pure color are placed very close together, and visually mix together to create changes in value. • 1. • 2. • 3. • 4. 5 6 Henri Matisse (French, 1869-1954), Dance (first version), 1909, oil on canvas, 8 feet 6 1/2 inches x 12 feet 9 1/2 inches (259.7 x 390.1 cm), Museum of Modern Art, NY. • 1. • 2. • 3. • 4. 7 Matisse painted a second version of Dance in 1910, oil on canvas, 102 x 154 inches (260 x 391 cm), Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. • 1. • 2. • 3. • 4. 8 Henri Matisse, Music, 1910, oil on canvas, 102 x 153 inches (260 x 389 cm), Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. • 1. • 2. • 3. • 4. 9 Umberto Boccioni (Italian, 1882-1916), Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio), 1913, cast 1972, bronze, 117.5 x 87.6 x 36.8 cm, Tate Gallery, London. • 1. • 2. • 3. • 4. 10 Robert Minor (American, 1884-1952), Pittsburgh, 1916, lithographic crayon and India ink, published in The Masses, no. 8, August 1916. • 1. • 2. • 3. • 4. By the way……….. • Robert Minor produced this drawing as an editorial cartoon, commenting on a 1916 steel workers' strike. He was among the first American editorial cartoonists to employ grease pencil and ink brush, when most were using pen and ink. He emphasized the thrust of the soldier's bayonet by drawing its direction as the counterpoint to that of the worker's body. The grace of this juxtaposition results in our feeling all the more shock at the sight of the pointed blade. Minor drew inspiration for this approach from such European masters as Francisco Goya and Honoré Daumier, coming to produce many such spare, forceful drawings as this. 11 Marcel Duchamp (American, born France, 1887-1968; in U.S.A. 1915-18, 1920-23, 1942-68), Nude Descending a Staircase, 1911-12, oil on canvas, 58 x 35 inches, Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA. Sometimes called Cubo-Futurists • 1. • 2. • 3. • 4. 12 Charles Burchfield (American, 1893-1967), September Wind and Rain, 1949, watercolor, 22 x 48 inches, Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, OH. • 1. • 2. • 3. • 4. 13 John Steuart Curry (American, 1897-1946), Fire Diver, 1934, watercolor on paper mounted on board, 22 1/2 x 15 1/2 inches, Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MO. • 1. • 2. • 3. • 4.