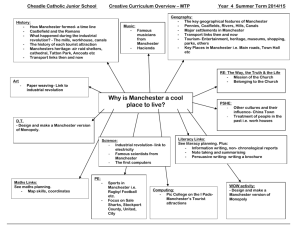

now - Manchester City Council

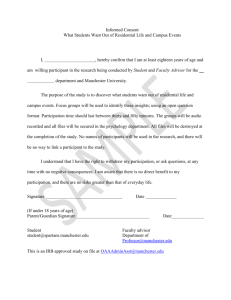

advertisement

Manchester A Sense of Place 2005: Thomas Heatherwick’s B of the Bang is the UKs tallest sculpture. It is taller than the Leaning Tower of Pisa and the Statue of Liberty 1964: The first Top of the Pops featuring performances by the Rolling Stones and The Beatles was broadcast from a disused church in Rusholme 1948: Worlds first computer with a stored programme design and built at Manchester University 1911 Ernest Rutherford discovered how to split the atom at Manchester University 1894: Marks and Spencer opens its first store in Hulme 1874: The first and only swing aqueduct in the world carries the Bridgewater Canal or the Ship Canal 1858: Halle Orchestra formed (the first professional permanent orchestra) 1858: Emmeline Pankhurst, founder of the Women’s Social and Political Union, born in Manchester 1857: The Art Treasures Exhibition held, the first international art exhibition 1653: Cheetham Library founded making it the oldest public library in the English-speaking world. 1.0 Introduction Sense of Place is a concept and a tool to engage with communities and individuals in different ways. By encouraging people to think about their place and space, what they want and what is important to them in different ways, the Council and our partners can engage more with people and they can engage more with us. This can help create better services and a better city. This framework: • Provides a definition of what Sense of Place is and how people in Manchester have defined their Sense of Place in the city • Demonstrates with case studies how we engaged with people in different ways to learn this • Sets out how Sense of Place is both a concept and a tool for community engagement at local and city-wide levels • Outlines how Sense of Place can be used in the future in community and city development, regeneration, service delivery, and in community cohesion and community engagement work. The Sense of Place work is designed to: • Inspire community engagement • Offer Council officers, professionals, our partners and people working with communities and individuals a challenge; to look at the city in a different way through the concept and tools of Sense of Place; examine new (and old) ways of working and ask ourselves – is this the best way? The Sense of Place work is not designed to tell people what their Sense of Place is, or should be, rather to enable people to articulate this. From October 2005 to January 2007, we carried out a programme of community engagement work to explore Sense of Place and create this framework. We also tapped into initiatives that were planned and developed by other organisations such as Urbis. The techniques are summarised in the table on the next page and are in this framework. The information from this was used to define Sense of Place and showed how we used Sense of Place as a tool for community engagement, identifying how it can be used more to carry out community engagement. When we use the term ‘community engagement’ in this framework we use the definition from the Manchester Community Engagement Strategy that encompasses six types of activity: The Sense of Place work has been carried out under the Manchester Community Engagement Strategy. If we ask questions in the same old way, we will get the same old answers. If we ask them in a different way, then we should start to get different responses. Community engagement can be hard. What may work in one area with certain people may not work as well with a different set of people. There are no absolutes and no one answer to every situation. Often, community engagement cannot be done quickly if we want a meaningful result. Sense of Place can also be a tool for engaging within organisations, to challenge assumptions we make as well as a tool to engage with communities and individuals. This Sense of Place framework is designed to help people on the community engagement journey. Sense of Place will change for people over time and not everyone’s Sense of Place is the same. However, what will stay the same is the need for Manchester City Council and service providers to understand the city, how it changes and evolves and how people and communities change. Case study Community engagement focus Sense of Place theme (0161) Project and Black is Young people, communities of identity, arts as a tool for engagement Belonging, identity, journey Georgina von Etzdorf project Engaging young people, arts as a tool for engagement Identity Community Radio Community media, devolution of decision-making, questionnaires, web-based discussions Community-based and run services, efficient and localbased working Sense of Place workshops Facilitation, workshops All Shudehill Bus Interchange Arts as a tool for engagement and urban design, partnership working (with university) Change, journey Community comics English as a second language (minority ethnic groups) Identity, place, change The Big Draw Arts as a tool, workshops Community Arts Workshops Refugee Week Communities of identity, families, children and young people, older people, BME groups Identity 2.0 Sense of Place in Manchester Sense of Place was defined as a feeling of belonging and regarding a place as home. This includes identity and having an affinity with an area. It includes experiences of a place – what makes a place unique to people, how this is understood and what makes Manchester meaningful to people. In a way, it defines what helps people stay in an area and why they feel part of it. In a broader sense it is a way for people to see themselves and their community. It is sounds, sights and smells that remind people of a place or are unique to that place. It is also people’s interpretation of this and an awareness of self and surroundings, of feeling connected to the community and the environment. It is seen as the present but it is often connected to the past and sometimes to the future: “A place where you can sit and reflect on your past and imagine a great future for yourself.” It is reflected in thoughts about the importance of the industrial revolution, “an epoch that fixed a Sense of Place and influenced the city for 200 years”. In addition to the importance of the past in a Sense of Place, there was also a focus on a sense of future, with changing faces, new people and communities coming into the city, with the city evolving around this. For example, “Being around Cheetham Hill, colours and sounds”, or “The diversity, new and different foods”. For the north of the city, a key part of Sense of Place is seen as the waves of immigration into the area, being both a benefit and a challenge. Religious sites such as mosques and cultural centres (like the Irish Club) reflect Sense of Place. This was felt as bringing something exciting to the area and a foundation to build on. The consultation showed that Sense of Place was felt to relate to past, present and future. However, our consultation showed that people did not have to live in a place for a long time to have their own sense of the place or affinity to it. Newly arrived communities highlighted how their Sense of Place – or belonging – was something they felt over a short period, especially if they had used public services to support their integration into the city and their ability to reflect their culture as well as the new British culture. “A feeling that you belong either as a visitor or someone who lives permanently somewhere... you are in the right place at the right time, that the place has rhythm.” During the consultation, Sense of Place was regularly attributed to specific places such as a library, a park, allotments, or a bus journey and was created by images and sounds that people related to – the number 53 bus was mentioned as an iconic route. Others attributed their Sense of Place to an organisation or a group to which they felt affiliated, with Hamilton Road Community Organisation and All FM mentioned specifically. A broader Sense of Place was identified in relation to the city, and this would often be just as strong with neighbourhood areas. An opposite, or being placeless, was identified as being part Sense of Place – a lack of belonging, feelings of isolation and powerlessness to be involved in the city. Participants and young people often related to and defined Sense of Place through a focus on people such as friends, family and neighbours. They related it to activities, such as music, sport and other opportunities, through entertainment and interaction with the artistic and cultural aspects of the city. It was not always a positive expression – “it’s just a place where I live.” However, people often related their Sense of Place in Manchester to parks, open space, rivers, local centres and locally run shops. Sense of Place was related to the roots of a tree and to routes in Sense of Journey. People strongly associated Sense of Place with belonging and the idea that people have roots in a place. Sense of Place was also associated with identity, which was often related to culture and backgrounds and the journey that people or their family and friends took to arrive in Manchester. Sense of Place can develop over time and be fostered, but not necessarily created all of a sudden for people. However, many said that their Sense of Place in Manchester can happen quickly in a few months (often fostered through family and friends and social and community networks) and that this can then evolve into deeper connections between people and place, sounds, colours, cultures and beyond. The consultation discussions often placed emphasis on the need for service providers and the Council to understand where people and communities come from, how they got there, the social norms, traditions and the culture, stories and experiences they bring that can be built on at a local level. This way, service providers can really tailor services to the specific needs of that community. Sense of Place was related to areas where people choose to live in and to where people have arrived, not so much out of choice, but necessity, where they have grown to feel at home because of community spirit and a feeling of belonging. The Council and its partners need to be aware that changing the city impacts on people both positively and negatively. Understanding the effects of change on people (for example, through regeneration) and factoring this into the planning and implementation of work was identified as important. Older people have suggested that the change of the city can affect them a lot and create a feeling of placelessness. Sense of Place is influenced by change and the changing needs of people and communities. Their identity, cultures and traditions need to be understood and properly considered in this change and reflected through the services delivered to people and communities. In turn, participants asked how change is considered by the Council and service providers and how it is understood through consultation and then managed, in particular regarding regeneration. Sense of Place develops over time and changes with circumstances. We have learned that Council officers, professionals and other service providers need to understand and learn the importance of place and space, its history, the culture now and where people have come from. It was felt that while this does change over time because communities aren’t static, ongoing dialogue through community engagement can help professionals understand this dynamic and plan their work accordingly. The importance of planning and urban design was raised as in connection with identity along with the potential to align Sense of Place more specifically to planning and urban design as the city develops. Sense of Place is not necessarily related to the length of time spent in an area. People who have spent a short time in a place can have just as strong links and have a real commitment to get involved in their local community as those who have been there longer. Some feedback referred to isolation, stereotypes or assumptions made of people, and these are detrimental to the idea of Sense of Place and include feelings of disengagement. A challenge is then created to understand why people feel this way and how this can be changed, in particular through community engagement practices. 3.0 Use of themes There were several contexts that were highlighted in the consultation where Sense of Place may be a useful tool or approach to use. • Marketing: This could include the promotion of neighbourhood identity and place with a larger city context, promoting not only Manchester but the neighbourhood make-up. • Regeneration: Housing and Planning. This was connected to Marketing, but highlighted as a way of ensuring that regeneration promotes the uniqueness of Manchester and fosters this. • Culture and Arts: Manchester’s arts and culture scene is viewed as central to promoting a Manchester Sense of Place at a neighbourhood and city-wide level. Sense of Place could be used to support and shape culture and arts programmes and approaches. • Community Cohesion: Sense of Place could be used to shape understanding of communities and service provision that is unique to specific need. This could include understanding difference, but also similarity between individuals and communities. 4.0 Strategic and localneighbourhood work Sense of Place principles and philosophy can be used in service delivery, regeneration, understanding communities and community cohesion. Manchester’s Community Strategy 2006–2015 sets out the vision for a world-class city and how success will be achieved. As a result, over the next decade the city, region and subregion will continue to grow economically and support a larger, wealthier, happier and healthier population. All actions by service providers working together is work that will enable children and adults to reach their full potential in education and employment. Neighbourhoods will be created where people choose to live and remain. Individuals will have pride in themselves, their neighbourhoods and their city, and demonstrate their respect accordingly. An illustration to demonstrate this is known as the ‘three spines diagram’. Sense of Place is an integral part of the third spine – Neighbourhoods of Choice, and it has a strong representation in the other two spines, particularly in the development of respect in communities. Manchester has five regeneration projects, which focus on regeneration at a neighbourhood level. Manchester City Council also has a system of Ward Co-ordination to ensure services delivered at a neighbourhood level reflect local need. Sense of Place consultation provides an ideal framework for discussions at a local level and the case studies are a good platform to build from, especially in the ongoing development of inclusive community engagement. Vision: Manchester – A World Class City Driven by the performance of the economy of the city and sub region. Reaching full potential in education and employment. Individual and collective self esteem - mutual respect. Neighbourhoods of choice Success – Larger population –wealthier, living longer, happier and healthier lives, Demographic mix (age and sex) Diversity, stability. 5.0 Sense of Place case studies The case studies show how Sense of Place can be a tool for engagement. They also show how Sense of Place can be combined with other engagement techniques such as community media, or workshops to engage with a range of communities such as young people. These case studies show how Sense of Place can be a way of approaching communities and discussing related services, such as regeneration, parks, leisure services and how these connect back to place. They also illustrate how different communities and individuals were brought together, showing how Sense of Place can relate to community cohesion. This is strongly illustrated in the Refugee Week workshops and the Victoria Baths restoration work. Case study: 0161 Project, Urbis This community-led project produced a fully interactive exhibition of Mancunian realisation and discovery. The initial consultation used a variety of tools and resources to engage with people, including surveys, (both hard copy and electronic), interviews, local radio and press, and local organisations. These included a cross-section of the community, Manchester City Council, Manchester universities, race relations, Granada TV, places of worship, local businesses, artists, local transport networks, schools and planners. This formulated an abundance of real stories, facts, experiences and considerations about Manchester’s past, present and future that was used to inform the basis and content of the 0161 exhibition. There were three sections to the 0161 exhibition: Memories, Belonging and Place. Memories used photographic portraits, personal histories, music, bygone extracts from Coronation Street and a range of factual statistics to illustrate Manchester’s journey from the industrial city to its current-day status. Visitors were invited to type their personal memories on a selection of old typewriters and the wealth of paper stories were displayed as part of the exhibition. Belonging focused on the current themes that emerged from the community: regeneration, housing, rubbish, accents and language. Again, visitors were invited to interact with the exhibition by adding to a Rubbish Tapestry, sending texts to a LED display and/or composing and presenting a postcard expressing a personal view on Why Manchester? Results from these interactions were gathered and visually expressed by the Urbis in-house artists. Place celebrated Pride in the City’s cultural diversity. Maps tracked journeys taken from various global regions to the ten boroughs of Greater Manchester; rolls of opulent fabric and containers full of spices from around the world enticed visitors to touch and smell. A blank recipe book invited everyone to share their favourite concoctions. Poets, both professional and recreational, joined to express their city pride in the Mancunian Wall of Verse. At the end of the exhibition, all community contributions were collated and analysed and a variety of themes emerged. The overwhelming conclusion presented by the Mancunian community was its sense of pride. Manchester is proud of its history, its maverick attitude that delivers innovation and change, but above all else, people are proud of its people, their singular characteristics and their diverse mix of culture and race. Case study: Black Is In October 2006, Urbis consulted with many of Manchester’s black residents about their identity and sense of belonging in the city. This was done simply through talking to people informally and receiving suggestions and referrals onto further interesting interviewees. People were asked to respond to the question ‘what does being black in Manchester mean to you?’ The answers were varied and exhibited a strong sense of pride and belonging. The comments relating to Moss Side were particularly interesting and will be a valuable tool in the regeneration process of this area. “We determine what the colour is: Black is a deep yet transient colour, From the red pain of slavery, To the blues of soulful music, Let’s bring the Mancunian spectrum, To the ebony tapestry that is Black History” Keisha Thompson, Aged 16 I wouldn’t even dream of living anywhere other than Moss Side, Manchester. It’s my home and it’s where I feel welcomed, safe and secure. I can be me. Not just a strange black face to feel threatened by. Case study: Georgina von Etzdorf project Manchester Art Gallery worked with the Ancoats-based AMP Youth Project to run a series of arts-based workshops. The aims of the workshops were to: • • Encourage young people’s interest in the Manchester Art Gallery and art and design Empower young people with new skills and encourage them to have fun. Young people from Ancoats, Collyhurst and Miles Platting worked with textile artist Zimeon Jones to create sculpture scarves. The scarves were made in response to the Georgina von Etzdorf exhibition at Manchester Art Gallery. The group took inspiration from the Gallery of Costume in Rusholme, and visited a regeneration area in Ancoats. Making their scarves gave the young people an opportunity to explore their personal identities and develop new skills. The workshops offered space to talk about the unique environment of Ancoats, as well as to represent their views of the area. The project was about listening to the young people and creating a sense of belonging in a place undergoing change. It was evident that the young people of Ancoats have a strong sense of pride and a Sense of Place. This project was an opportunity to discuss future plans for the area; young people often feel detached from regeneration and see it is something that happens around them. The young people that took part in this project had previously never been to Manchester Art Gallery; some had never been to Rusholme, and although they knew St Peter’s church, they had never been inside. The young people independently visited the Central Gallery on a Saturday to see photographs of their artwork on display. Case study: Radio All FM consultation – devolved decision-making and budget As part of the consultation programme for exploring Sense of Place in Manchester, All FM was commissioned to carry out radio programming on Sense of Place. All FM is a community radio station based in Longsight. Details about the station are on www.allfm.org. A small pot of money was given to the station to carry out consultation in a way that was best for them and their audience. This included decision-making power on how the consultation would be carried out. A contract in the form of a letter set out the minimum requirements for the consultation. This included: • To talk to local people about what they think Sense of Place means • To learn about local people’s Sense of Place or lack of it • To carry out consultation within a set timeframe. There was no requirement to talk to a specified number of people. Priority was placed on the range of people (age, area and gender for example). Decision-making on how this was done was left to the radio station. Online surveys were carried out as well as vox pops through interviews with people on the street, at supermarkets, at events and in parks.This approach represents a way of devolving decision-making and budget to a community-based organisation to carry out consultation. Case study: Sense of Place workshops As part of the consultation about Sense of Place, we carried out workshops. These workshops ranged from eight people with interpreters, to 250 people in the Great Hall of Manchester City Council’s Town Hall. Regardless of the numbers and identity of the participants (young people, older people, English as a second language groups), we finished with a model that can be used either as an icebreaker for discussions for exploring place and belonging as part of regeneration, or for service delivery consultation. Icebreaker – personal • You wouldn’t know it, but I’m very good at... • When I was young I wanted to be... • My favourite travel moment • A book/film that changed me • I wish I’d never worn... This can be a fun icebreaker that fits neatly with Sense of Place. This worked well incorporated into introductions of participants (names, where people are from, their role). The facilitator asked participants to pair off and to introduce themselves to each other with their name, where they are from, and their role. After this, they discuss up to three of the questions above (listed on a flip chart at the front of the room). Five minutes for this discussion is ample time. Participants then feed back their own information to the group – their name, where they are from, their role, and their answers to one of the questions. Icebreaker follow up – for the city and thinking about place differently If Manchester was a sound, plant, or vehicle, what would it be and why? This icebreaker is not appropriate for every group and the facilitator needs to have a good understanding of the group’s make-up in advance. However, it is a useful tool for helping people to look and think about their neighbourhood or city in a different way. It is a good follow-up to the personal icebreaker above. It is important that the facilitator explains why these questions are being asked. In the Sense of Place workshop context it was designed to get people thinking about their area in a different way as a warm-up exercise before exploring Sense of Place. Context – Sense of Place presentation After the warm-ups, there was a small presentation about what the consultation was trying to achieve. We outlined ideas behind Sense of Place and why the meeting was being held. The presentation wasn’t prescriptive on what Sense of Place is or isn’t, but it tried to put forward ideas to get participants thinking. Sense of Place – what do you think Sense of Place may mean? Participants discussed what they thought Sense of Place means to them. This was done in small groups where scribes wrote down feedback on flip charts. Sense of Place – what is your Sense of Place (or lack of it), in your local area or in the city of Manchester? Participants discussed this and scribes wrote down their comments on flip charts. General discussions The scribes fed back the results to the wider group, after which discussions took place with more notes taken from this. Remember: • Always clearly state why this is being done. In this context it was to consult and get ongoing interest • Always feed back the results on the day or after. What will be done with this information? How can people get involved? • Use a trained facilitator to run the discussion and use facilitators to take the notes from each group • Follow the guidance in the Manchester Community Engagement Toolkit on how to run meetings and discussions. Case study: Shudehill Bus Interchange In 2006, a group of MA students at Manchester Metropolitan University were asked to look at this recently developed bus and tram interchange to develop its identity and give it a Sense of Place. This was part of their coursework for the year. This project reflects an interpretation of Sense of Place as a tool for innovative engagement. The project began with historical and architectural research, spending time observing people at the interchange, going on journeys and listening to stories from local people as well as passengers. The major theme that came out of the initial research was a constant need for identity, something that would make Shudehill stand out from the rest of Manchester. The team discovered a mutual feeling of a space where many people gather, but actually pass each other by. Thinking about the movement of those people coming and going through the space without really being aware of their surroundings, the team focused on the idea of flow. This linked the present to the past: how the area used to be prominent in the cotton industry with cotton flowing through the spinning machines; bustling markets and how things are constantly moving and changing. The team used this information to suggest design and development of the interchange. They also experimented with live performances (dressed as pigeons) to share these ideas with commuters. This could be used as an innovative way of engaging with people to explore the design development of the area. Case study: Community comics The Community Pride Initiative ran a community comics project in Chorlton. The project involved a group of adult English as a Second Language students. An artist ran a session teaching drawing skills and how to develop a storyline to communicate messages through drawing. The students then used these skills to draw comics reflecting their experiences of Manchester and their local area. The students came from a range of countries (such as Iraq and Pakistan) and expressed their interpretation of Sense of Place and what created a Sense of Place for them in Manchester. The project served as a way of engaging with the students for this project and created new relationships for ongoing engagement. Case study: Black History Market and Big Draw on 1 October 2006 This Big Draw event was a multicultural event open to all. Participants explored their heritage through the context of a market at Victoria Baths, a place where people have always gathered to be entertained, gossip and enjoy themselves. One of the activities was the Big Draw, which is a national event intended to encourage drawing. Artist Stephen Wiltshire opened the event and drew the outside of the building. His drawings of buildings show a masterful perspective and reveal a natural artistry. With the support of another community artist, Kevin Dalton-Johnson, visitors were encouraged to interpret the Baths in different ways – in particular how they relate to the space and place, or their Sense of Place with the building as a hub of the community. This community engagement challenged perceptions and assumptions. In this way residents were engaged, and visitors and participants defined their own sense of place, exploring their own culture and identity, their connections to the place and their experiences within that place. With a community artist leading the workshops, we worked with local residents to develop drawings that will encourage a sense of pride and identity in their own environment. This uses art as a tool that can be used by visitors to define their own sense of belonging and explore their own culture, their connections and their experiences in Victoria Baths. Case study: Community Arts Workshops As part of Refugee Week in 2006, a community artist was commissioned to consult with people attending three events in north Manchester exploring their interpretation of Sense of Place and how they have a Sense of Place in Manchester. The artist set up a stall and invited children, young people and their friends and families to create images of their homes and community and to discuss this. Another aim of the Sense of Place arts workshops was to get people from different backgrounds to use art to enjoy themselves. They were also encouraged to talk to others so they could experience different cultures and perspectives, in particular through the Sense of Place discussions. The themes that emerged were built into the Sense of Place framework, but the workshops also showed how this approach can be a way of supporting community cohesion – or bringing people from different backgrounds together to explore difference and similarities. 6.0 Profiles of initiatives using Sense of Place principles The short summaries below show how Sense of Place principles and approaches are being used now and could be used to inspire future work. Sense of Place in the Local Development Framework Manchester’s Local Development Framework will provide the planning policy framework for the city’s development over the next 20 years. One of the first documents being prepared is the Guide to Development in Manchester, which sets out design principles to guide developers and others involved in shaping Manchester. The Guide aims to ensure that the developments taking place throughout Manchester enhance and contribute to the unique identity of individual areas within the city so that Manchester’s many neighbourhoods retain and develop their own Sense of Place. There are many factors that create a Sense of Place, some in a direct and obvious way (such as the appearance of buildings, or the presence of a park), others in a less tangible way – having a good choice of shops or being close to friends and family. Wythenshawe One World Festival New people can change/challenge a Sense of Place. The Wythenshawe Old World Festival was an event to highlight the positivity of the increasing ethnic diversity in Wythenshawe by inviting people to get together and share their cultural traditions, express their identity and enjoy themselves safely in the town centre. Approximately 600 people attended the event, which had a family-friendly and positive atmosphere. The event was the first of its kind to be held in Wythenshawe. Life Through a Lens Different people see places differently. The Life Through a Lens project brought together both younger and older people in Collyhurst and Harpurhey. The younger participants took photographs of the area, stimulated by the conservation of the Collyhurst war memorial; the older people shared their old photographs and their memories. This helped to create a shared knowledge and experience of the area, fostering more respect and a sense of ownership and pride in the local area between the generations. The project culminated in an exhibition of the work on Veterans’ Day at the new North City library. My Place, My Space My Place, My Space is a theme that people can respond to on a personal and community level from a garden to a state of mind, from a street to a city. This is the concept for the Maine Road Art Programme, developed to complement the regeneration of Maine Road and the wider Moss Side area by actively involving residents in the creative development of their neighbourhood over the next four years. Pupils at St. Edwards Primary School created a mural in response to their changing environment, and young men from Moss Side took part in a street dance project that explored their ideas of identity and community. People are responding enthusiastically to being part of My Place, My Space. 7.0 Manchester Community Engagement Toolkit and acknowledgements This framework is a stand-alone document, but is also an update to the Manchester Community Engagement Toolkit, as it illustrates different types of community engagement in action. The work has been carried out under the Manchester Community Engagement Strategy work programme. The toolkit and strategy can be downloaded at: www.manchester.gov.uk/bestvalue/engage. When carrying out Sense of Place work, we recommend that people use the Key Skills set out in the toolkit: • Planning (page 7) • Monitoring and Evaluation (page 8) Other skills may be used, such as: • Effective meetings (page 9) • Facilitation skills (page 12) • Presentations (page 14) • Clear and jargon-free writing (page 16). This framework was developed by Patrick Hanfling, Patricia Allen, Sarah Benjamins, Claire Freeman (Manchester City Council) and Sophie Fosker (CN4M). The Sense of Place programme was inspired by work carried out by the Community Planning Group of Auckland City Council, New Zealand. Participants and contributors have included Council Officers, members of the Manchester Partnership, the Community and Voluntary Sector, other Councils and professional bodies. Len Grant (www.lengrant.co.uk) has kindly provided all the photos except for the picture of Rusholme, taken by Mike Pilkington. Thank you to all involved! Please contact us if you wish to reproduce the information here so that the appropriate people can be referenced. Contact the Community Engagement Development Officer on 0161 234 4093. If someone you know would like to obtain a copy of this in another language, Braille, large print or on tape, please phone 0161 234 4093 or fax 234 3055.