File

advertisement

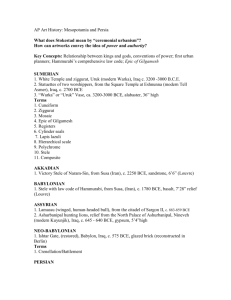

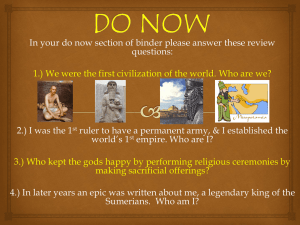

6 CHAPTER 2 ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN ART In ca. 4000 BCE large urban communities began to emerge in Mesopotamia in the area between the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers. The earliest writing system consisting of pictograms appeared ca. 3400–3200 BCE, and by ca. 2900 BCE these were refined into a series of wedge-shaped characters known as cuneiform. During this period art was used to reflect political power, expressing stories through art. Sumerian Art Key Images Remains of the ″White Temple″ on its ziggurat, p. 24, 2.2 Interior of the cella of the ″White Temple,″ p. 24, 2.4 Female Head from Uruk, p. 25, 2.5 Statues from the Abu Temple, p. 26, 2.6 Royal Standard of Ur, p. 27, 2.8 Bull Lyre, from the tomb of Queen Pu-abi, Ur, p. 28, 2.9 Inlaid panel from the soundbox of the lyre, p. 28, 2.10 Priest-King Feeding Sacred Sheep, p. 29, 2.11 Religion In Mesopotamia we see the emergence of a polytheistic religion. Sumerian beliefs were centered around the concerns of everyday life and Sumerian gods and goddesses were powerful and immortal. Often we find an association of animals with these deities. Deity Attribute An (Anu) Inanna (Ishtar) Sky god and head of the pantheon Queen of Heaven, spouse of Anu Goddess of fertility, love, war God of vegetation God of wisdom ″Lord Breath,″ god of atmosphere Storm god Sun god Abu Enki Enlil Imdugud Shamash The first major civilization in Mesopotamia, dating to ca. 4000 BCE, was several citystates in the southern region of Sumer near the junction of the Tigris and the 7 Euphrates rivers. These cities flourished until ca. 2340 BCE. The cities in this region are known collectively as Sumer. The Sumerians developed a form of writing called cuneiform. Each city had a civic god. The administrative staff for the city was based in the city temple, and the temple staff supplied area farmers with seeds, tools, and work animals. The farmers would donate a portion of their produce to the temple. In this way, the civic god, in conjunction with the ruler of the city, governed the city with a system called theocratic socialism. There were two types of Sumerian temple. The ″low″ temples rested on ground level, while the ″high″ temples were on a raised platform. These platforms were gradually transformed into temples known as ziggurats. These temples served as a bridge between heaven and earth. The most famous literary work of Mesopotamia is the Epic of Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh carved his story on a stone marker—reinforcing the relationship between relief sculpture and narrative in Sumerian culture. The identification of the Tell Asmar figures is controversial. While some scholars believe that they are supposed to represent Abu and his consort, most consider the entire group to represent worshippers. The style of these figures is abstract. The grave goods from the Great Death Pit in Ur are particularly rich, suggesting the elite status of many of the dead. The Royal Standard of Ur shows the early development of visual narrative, with scenes depicted in distinct registers. In one of the more lavish tombs in Ur, the tomb of Queen Pu-abi, a lyre with a bull’s head of gold gilt and lapis lazuli was found. The front panel of the lyre depicts a narrative scene of unknown meaning. Cylinder seals, cylindrical objects carved with a design so that when impressed on clay it would leave a raised reverse image, emerge during this period. These seals would have been used to record business transactions and keep track of inventories. Akkadian Art Key Images Head of an Akkandia Ruler, p. 29, 2.12 Stele of Naram-Sin, p. 30, 2.13 During the period of Sumerian power, a people known as the Akkadians settled the area near modern Baghdad. 8 Under the rule of Sargon I, the Akkadians conquered the Sumerian cities and brought most of Mesopotamia under their control. The bronze Head of an Akkadian Ruler from Nineveh is most likely a representation of Sargon I, although some suggest that it could represent his grandson, Naram-Sin. The themes of power and narrative are combined in the Stele of Naram-Sin which commemorates Naram-Sin′s victory over the Lullubi. In this stele, Naram-Sin wears the horned hat of divinity, which suggests the divinity of the ruler. Neo-Sumerian Revival Key Images Great Ziggurat of King Urnammu, Ur, p. 31, 2.14 Head of Gudea, p. 32, 2.15 Seated Statue of Gudea Holding Temple Plan, p. 32, 2.16 The rule of the Akkadians ended when the Guti gained control of the Mesopotamian Plain. The Sumer drove them out in 2112 BCE under the leadership of King Urnammu of Ur,who reestablished Sumerian as the state language and began constructing buildings on a large scale. The Great Ziggurat at Ur is dedicated to the moon god Nanna. Statues from Lagash, carved of diorite, attest to the piety and wealth of Gudea, the ruler of Lagash, one of the smaller Sumerian city-states. Bablyonian Art Key Images Stele of Hammurabi, p. 33, 2.17 The Babylonians established a powerful dynasty centered around the city of Babylon. The founder of this dynasty was Hammurabi (c. 1792–1750 BCE) whose law code, one of the earliest written bodies of law, lists 282 regulations dealing with commercial and property matters as well as domestic problems. The law code is inscribed on the lower portion of the Stele of Hammurabi. Above the code in high relief, Hammurabi stands before Shamash raising his hand in a greeting to the god who, in turn, extends the rope ring and measuring rod of kingship to Hammurabi. Regional Near Eastern Art: The Hittites 9 Key Images The Lion Gate from Bogazköy, Anatolia, p. 38, 2.23 Babylon was overthrown by the Hittites in 1595 BCE. The Hittites adopted cuneiform writing for their language. The Hittite Empire reached its height between 1400 and 1200 BCE. The lions of The Lion Gate were probably inspired by the Assyyian lamassu, serving the same function. The Phoenicians Key Images Ivory plague depicting a winged sphinx, p. 39, 2.24 The Phoenicians were seafarers, founding settlements throughout the Mediterranean and conducting active trading. Particularly skilled in metalwork, ivory, and making colored glass, they incorporated motifs from Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean coast into their art, strongly influencing Near Eastern art. Assyrian Art Key Images Gate of the Citadel of Sargon II, p. 35, 2.19 Fugitives Crossing River, from the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II, p. 36, 2.20 Lion Hunt relief, p. 36, 2.21 The administrative center of this empire was the palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud. The theme of Assyrian art was the power of the ruler, reflected in reliefs which were decorated with the details of military campaigns that communicated the invincibility of this powerful empire. Large guardian figures known as lamassus protected the palaces. Late Babylonian Art Key Images Ishtar Gate from Babylon, Iraq, p. 37, 2.22 10 After the Assyrian empire fell to the Medes in 612 BCE, the city of Babylon witnessed one final brief flowering between 612 and 539 BCE, before it was conquered by the Persians. The most well-known Late Babylonian ruler was Nebuchadnezzar II (ruled ca. 604– 562 BCE), who was a strong commander. He was responsible for building the renowned Hanging Gardens of Babylon, considered one of the wonders of the ancient world, as well as the Ishtar Gate. Iranian Art Key Images Painted beaker, from Susa, p. 39, 2.25 Early nomadic tribes left no permanent structures, but grave goods reveal the extent of their migrations. These objects were made of wood, bone, or metal, and often have animal motifs used in abstract and ornamental ways. Persian Art Key Images Rhyton, p. 40, 2.27 Audience Hall of Darius and Xerxes, Persepolis, p. 41, 2.28 Bull capital, Persepolis, p. 41, 2.29 Darius and Xerxes Giving Audience, p. 42, 2.30 The Persian Empire is the successor to a long progression of Mesopotamian kingdoms, extending from Greece to the Himalayas and from southern Russia to the Indian Ocean. Persian kings did not construct religious architecture, instead they constructed vast royal palaces, the most ambitious of which was at Persepolis. Persian culture was derivative, eclectic, and highly refined. An example of the Persian style can be found in the Rhyton and the painted beaker from Susa, each an example of the ″animal style.″ Sasanian Art: Mespotamia between Persian and Islamic Domination Key Images Shapur I Triumphing over the Roman Emperors Philip the Arab and Valerian, p. 43, 2.31 Palace of Shapur I, p. 43, 2.32 11 King Peroz I Hunting Gazelles, p. 44, 2.33 In 331 BCE Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE) defeated the Persians, burning the palace at Persepolis. Alexander the Great′s empire was divided among his generals after his death, and Seleukas (ruled 305–281 BCE) inherited a large portion of the Near East. Shapur I (ruled 240–272 CE) expanded the empire, defeating three Roman emperors in the mid third century CE. These military victories were commemorated on several reliefs including Shapur I Triumphing over the Roman Emperors Philip the Arab and Valerian. Ironically, in this relief Shapur I appropriates Roman iconography of triumph. Key Terms/Places/Names Mesopotamia cuneiform ziggurat theocratic socialism Gilgamesh votive statues Abu registers hieratic scale cylinder seals frontality Sargon I Naram-Sin stele buttresses lamassu Nebuchadnezzar orthostats ground-line fibulae Gudea Hammurabi Darius I rhyton apadama Shapur I iwan iconography blind arcades 12 Discussion Questions 1. Compare and contrast Sumerian sculpture with that of Egypt being done at the same time. 2. What sorts of messages were encoded in Babylonian and Assyrian art? In what ways could these messages be considered propagandistic? 3. Define and give an example of a ziggurat. How does the ziggurat differ from Egyptian pyramids? 4. Discuss the animal style and its use in Persian art. Give examples of its use. Resources Books Kramer, Samuel Noah. History Begins at Sumer. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994. Kuhrt, Amelie. The Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–330 BC. Vol. 1, From c. 3000 BC– c. 1200 BC. New York: Routledge, 1997. Leick, Gwendolyn. A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology. New York: Routledge, 1998. Pollock, Susan. Ancient Mesopotamia: The Eden that Never Was. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Stiebing, William. Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. New York: Longman, 2003. www (The Avalon Project, Yale Law School) The Code of Hammurabi http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/medieval/hamframe.htm