Pugach, Marleen C. (2006). Because teaching matters, (pp. 95

advertisement

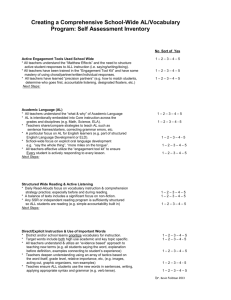

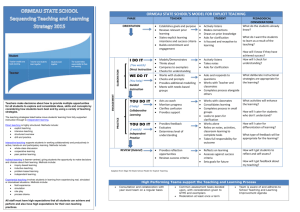

Pugach, Marleen C. (2006). Because teaching matters, (pp. 95-99). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Due before class time this Wednesday January 13th (this week!). 1. If someone were to ask you “What is curriculum?”, an easy answer might be “Curriculum is what we teach our students; it’s what they’re supposed to learn”. But according to this Reading, it’s not as simple as that. Why? 2. Ok, now that you’ve read Pugach’s discussion and thought about some of the complexity of curriculum, what might you say now if someone were to ask you, “What is curriculum?” Offer some explanation as to why for now you think this might be a workable definition. Come to class on Wednesday prepared to share your working definition of curriculum. page 95 CURRICULUM: A MULTIDIMENSIONAL CONCEPT The term curriculum seems like it should be straightforward enough to understand. According to Eliot Eisner (1979), a respected scholar of curriculum in education, the term originates from the Latin word currere, which means “the course to be run” (p. 34). The idea is that there is a set course, or program, of study that students are to complete in order to be considered well educated. As we noted earlier, the curriculum represents what is considered worthwhile for students to learn during the years they spend in school. The Explicit Curriculum — What It Is and Is Not We can think of the formal, written academic program of study that guides teaching as the explicit curriculum (Eisner, 1979). Larry Cuban (1992), another scholar of curriculum, uses the term official or intended curriculum to describe the formal academic program of study. These terms convey essentially the same message: the explicit, formal academic curriculum is a public statement of what a particular school district or state believes is worthwhile for students to know in each content area. As such, it sets the broad Critical Term: explicit parameters for what you will teach. The explicit curriculum. The formal, curriculum is usually a public document or series of official, public academic documents, and today these documents can typically program of study that be accessed online through school district or state defines what students are educational agency websites. It represents the expected to know as a endpoint of your teaching — what your students result of being in school. should know. As a general rule, two kinds of documents usually define the formal program of study or the explicit curriculum: academic content standards and curriculum guides. Academic content standards are statements of what students should know and be able to do in each of the major content areas upon completing their P-12 education. This knowledge is usually assessed in required standardized tests administered by the state. Building on these standards, curriculum guides give detail and resources regarding how the various subjects might be taught. The concept of the explicit curriculum sounds simple. You are handed standards and curriculum guides, and you develop teaching plans from these materials. Districts purchase instructional materials, such as textbooks, software, and laboratory equipment, to support the course of study that has been identified as worthwhile. As a Critical Term: academic content teacher, you can draw on these resources standards. Formal, public statements of and materials to help you plan your own what students should know and be able to instruction. It is essential for all teachers do in each of the content areas at various to know the academic standards for their points in their P-12 education. subject and grade level, and curriculum guides can help interpret those standards. But none of these documents tells you what to do each day in your classroom. They provide a destination only, a statement of what your students should know and be able to do as a result of the instructional program you create and implement for your students. A set of standards and curriculum guides does not actually tell you how to teach to those goals. So in reality the concept of Critical Term: curriculum guide. A curriculum is much more complex than the document prepared at the state or local sum of a set of documents, however useful district level that provides detailed they may be. To do their work well, teachers information to help teachers plan use their knowledge of the standards, the instruction. subject, and pedagogy to plan instructional units and lessons that will help them achieve the curriculum goals for that grade page 96 and content area in relationship to the particular group of students they are teaching. Therefore, what is stated in the explicit curriculum is not exactly the same as what is actually taught. In addition, just because teachers teach “the curriculum” does not necessarily mean that students learn it. Cuban (1992) coined the phrases the taught curriculum and the learned curriculum to describe how curriculum plays out in the classroom in terms of what is actually taught and learned. Finally, it is also important to consider both what is and what is not included in the explicit curriculum. Eisner calls everything that is not contained in the formal, explicit curriculum — everything that is left out to begin with — the null curriculum (1979). The null curriculum, as we shall see, represents those things that are not valued as important enough to be part of the formal program of studies. In Chapter 5 we will take up a third dimension of curriculum, namely, the hidden curriculum, which is defined as all the things students learn by virtue of being in school that are not part of the explicit curriculum. Curriculum as What Is Taught As soon as teachers plan what to teach, they are making choices about how they will deliver the explicit curriculum. Through their interpretations and choices, teachers begin to change the curriculum, introducing their own preferences and beliefs (Cuban, 1992) — hence, the taught curriculum. For example, teachers may spend valuable instructional time on one aspect of the curriculum instead of Critical Term: taught curriculum. The another, or they may convey to their curriculum that is delivered by teachers students that one feature of the once they make decisions about how to curriculum is more important than teach the explicit curriculum. another. A teacher may teach one part of the curriculum in an engaging, motivating way but another in a less motivating way. He or she may use some prescribed curriculum materials and not others. Each such choice affects the content of that curriculum for students and shapes how they understand and The academic curriculum is not learn it. Making these choices is a just what a teacher is supposed regular part of teaching and illustrates that teachers to teach, but also includes what have some degree of autonomy in interpreting the the teacher actually chooses to curriculum in their own class rooms. The choices teach and what the students teachers make about the curriculum let them learn. (Media Bakery) put their own personal stamp on what and how they teach. Teachers often thrive on the freedom to emphasize the topics and projects that motivate them most — and in turn motivate their students as well — within the broad scope of the explicit curriculum. The challenge, of course — and what represents an enduring curriculum dilemma — is to make those choices in relationship to the goals of the curriculum in a manner that maximizes your own students’ learning of the curriculum. As a teacher you are responsible for making sure your students learn what they are supposed to learn at any given grade level in a way that is meaningful for your students and that engages them in learning. To do that well, you must first be familiar with the academic standards — the goals of the curriculum under which you are teaching. The concept of the taught curriculum also has implications for the teachers who will work with your students in subsequent years. Teachers are responsible for preparing their students for the next level of work they will be expected to perform page 97 in school. Those aspects of the curriculum you emphasize (or choose not to emphasize) may or may not lay the foundation for the curriculum in the upcoming grade level. In other words, you are part of a school community where ideally teachers work together, in a coordinated way, to foster all students’ learning. Curriculum as What Is Learned But as we stated above, what you teach is not always what your students learn. It is not enough for teachers to be concerned with presenting content; they must also be concerned with the effects of their teaching on their students. This is what makes the concept of the learned curriculum useful. The goal of teaching is to ensure that students learn what you set out for them to learn. How will you know if your teaching has a made a difference? What students actually learn in relationship to the explicit curriculum is determined in large part by the choices teachers make and the events they enact Critical Term: learned curriculum. What in the classroom. To be sure, some students actually learn in relationship to the teachers who teach disregard the extent goals of the explicit curriculum — which is to which their students are learning, but not always the same as those goals. these teachers are not carrying out their professional responsibilities well. That is why Cuban (1992) and other curriculum scholars are concerned not only with what is supposed to be taught and what is actually taught, but also with what students actually learn as a result of teaching. You probably recall at least one class during your own P-12 education where the teacher simply stood up and lectured each day, expecting you to recall the facts in that particular content area. You probably also recall that you didn’t learn all of these facts perfectly — if at all. Your teacher was likely teaching from instructional materials that were aligned with the explicit curriculum, hoping that there would be a direct transfer of factual knowledge from him or her to you, the students. Your teacher taught, but what you learned did not match what was taught. Teachers may choose to present content in this rote manner, but if they do, their students may not always learn the material well — despite the fact that it is in the explicit curriculum. If teachers want their students to learn the explicit curriculum, standing up day after day and telling students what is in it is not a particularly effective way of teaching — and certainly not a guarantee that they will learn. To ensure that students learn, teachers must figure out ways to make the content of the curriculum meaningful to their students and connect the content to their students’ lives. This might include a good lecture or teacher presentation of information now and then, but continuously relying on this approach does not engage students well. Reaching students on a daily basis requires that teachers make choices not only about what they teach, but about how they will teach so that their students learn. The explicit curriculum is meaningless if teachers are not concerned about the degree to which their students are learning. To determine whether students have learned what they are taught, teachers continuously assess how their students are doing. By observing students carefully, by listening to them during discussions, by evaluating students’ written work, by conferencing with students individually, and also by testing students, teachers keep track of their students’ learning. The information teachers gain through ongoing assessment not only enables teachers to document their students’ learning; it also provides teachers with feedback on how well they are teaching. For example, let’s say that a teacher in a middle school social studies class has just completed a unit on supply and demand. A follow-up homework essay shows that 80 percent of the class does not understand these concepts. The results of this essay provide the teacher with feedback on how well the students learned the page 98 material. Recognizing that the majority of the class did not do well, a teacher might ask him- or herself, “What can I do differently to ensure that my students ‘get’ these concepts?” “How can I represent these concepts more effectively?” Teachers who do not ask themselves such questions and who do not use feedback from students’ work to improve their own practice are not demonstrating a reflective approach to their work and are not carrying out their professional responsibilities well. If only one or two students did not understand the material, the teacher’s response might be to figure out how to provide additional support to those few students. In either case, assessing students systematically provides teachers with an understanding of how well the taught curriculum translates into the learned curriculum. Figure 4-1 The Relationship among the Intended, Taught, and Learned Curriculum. Source: Adapted from Cuban. L. (1992). Curriculum stability and change. In P. W. Jackson (Ed.), Handbook of research on curriculum (pp. 216-247). New York: Macmillan. Figure 4-1 illustrates the relationship between the explicit, the taught, and the learned curriculum and identifies the levels at which each dimension of the curriculum plays out. These three aspects of the curriculum are in constant interplay page 99 in the classroom and reflect not only the teacher’s choices about what and how to teach, but also the interactions between teachers and their students. How to balance the competing demands of the explicit and the taught curriculum in relationship to pressures to demonstrate what students have learned is a dilemma all teachers face. Moreover, the relationship among these three dimensions of curriculum can change over time. When such changes occur, they can have a profound influence on the day-to-day choices teachers make about the curriculum. For example, when the pressure of standardized testing is great, teachers can feel constrained in what they do in the classroom and how they use their instructional time. As teachers gain greater experience, however, they can become more skilled in balancing the autonomy they have in the classroom with the requirements of the explicit curriculum. What Isn’t Taught — The Null Curriculum The explicit curriculum does not include everything it is possible to know, nor does it include every perspective on that knowledge. Rather, the explicit curriculum is one “take” on knowledge and on what is important to know. By necessity, much is excluded. Another way to think about what curriculum is is to consider everything that is not taught in school. As we noted earlier, Eliot Eisner refers to all that is not included in the public, official, explicit curriculum and is not taught as the null curriculum. What schools do not teach is also a statement about what is — and is not — valued in P-12 education. If a high school requires four years of mathematics, but music and art are taken only as Critical Term: null electives, then for many students music and art are part curriculum. Everything of the null curriculum. If a school offers only one foreign that is not included in the language, then all of the other foreign languages are part explicit curriculum, and of the null curriculum. These are the subjects students thus, is not expected to be have no opportunity to study in school — subjects that learned during a student’s are not deemed to have sufficient worth or value to P-12 education. include in the curriculum. Similarly, if students only read literature and poetry written by European or European American male authors in their English classes, the null literature curriculum consists of all of the other works of fiction and poetry by racial and ethnic minority male and female authors and European or European American females to which students will not be exposed in school. As a result of defining the curriculum in this way, students who live in a multiethnic, multiracial society do not have the opportunity through literature as it is taught in school to gain perspective on the life experiences and issues represented by the works of a broad range of authors. A different example of the null curriculum can be found in current views of history that students often learn relating to Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. Until recent years, when teachers taught the story of Columbus, the “null” curriculum consisted of the native perspective. Today Columbus’s arrival in the new world, marking the start of major European settlements in the America, is also viewed as negative because it was destructive to the indigenous people already living here. Thus, what is not included in the explicit curriculum is just as much a statement of values in education as what is included. The concept of the null curriculum reminds us that multiple perspectives exist about what is important to know — more than what may be included in the official program of study teachers are given. Choices that are made about what goes into the explicit curriculum are simultaneously choices that are made about what is not considered important. These choices express values about what is or is not worth teaching and what is or is not worth having students learn as a result of their P12 schooling.