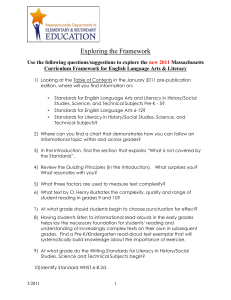

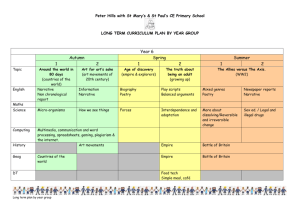

Student/Teacher Resource

advertisement