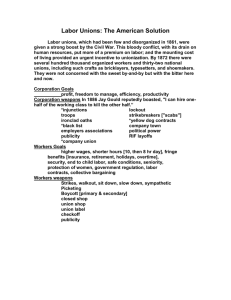

The Development of Labor Unions

The Development of Labor Unions

"To be free, the workers must have choice. To have choice they must retain in their own hands the right to determine under what conditions they will work." -Samuel Gompers

From the late 1700s onward, factory work gradually replaced the system of home-based production known as the cottage industry. Rural, water-powered mills, were replaced by urban, steam-driven factories, filled to the roof with chugging, hissing, clunking machines. A task once accomplished by a group of skilled artisans became a thoughtless chore completed by, and depending on, faceless, nameless cogs in an assembly line.

Employers soon realized that if factories were built in cities, there would be a larger supply of workers available. With more people willing to do the work, employers felt that they could cut wages, and put more money into their own pockets. Naturally, employers wanted to maximize their profits. That meant that men, women and children were hired for very low wages, usually worked in dangerous or unhealthy conditions, and often worked for twelve or more hours.

Industry in America developed far more rapidly than it had in Europe. Factories and mills spread quickly throughout New England prior to the Civil War due to good supplies of natural resources such as iron and coal, and the ease of transporting finished goods along the many navigable rivers. This in turn lead to the building of more railroads and canals to handle the increased traffic.

In addition, immigrants from Europe were swelling the labor pool, allowing employers to drive wages lower and lower. The combination of unsafe and unhealthy working conditions, extremely long work days, and the growing number of people (especially children) injured or killed working at mills, led to the organization of concerned groups of labor unions in the United States. Most unions wanted to lower the total hours worked per day, raise wages, and outlaw child labor. Some were more successful than others.

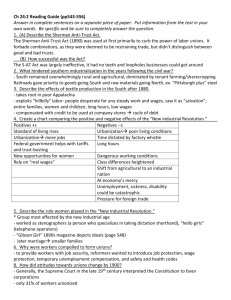

Efforts at National Labor Unions

In 1866, a new organization called the National Labor Union called on Congress to order an eight hour workday. The National Labor Union was a group of farmers and reformers that wanted Congress to pass labor reforms. Although the National Labor Union failed to convince Congress to shorten the workday, its efforts made the public aware of labor issues. It also increased public support for labor reform before it broke up in 1873.

The Knights of Labor , founded in Philadelphia in 1869, were more successful. The union was organized by industrial workers who welcomed women, blacks, and even accepted employers, an uncommonly open attitude at the time. The Knights of Labor tried to expand their appeal through demanding an eight-hour work day, and the end of child labor. By 1886, the Knights of Labor, who accepted both skilled and unskilled workers, counted over 700,000 farmers, laborers and shopkeepers among its members. The union discouraged the use of strikes and supported remaking society along more cooperative lines. Many

Americans considered such ideas socialist or communist thinking, and opposed labor reform movements because of it.

In 1886, a series of violent strikes by railroad workers stained the union's reputation. Police were called in when fighting broke out between striking workers and strikebreakers at the McCormick Harvesting Machine

Company in the Haymarket area of Chicago, Illinois.

Two union men were shot by police. Later an explosion killed seven policemen. Although the person who set off the bomb was never identified, four labor leaders were convicted of conspiracy to commit murder and hanged. The Haymarket Riot made the idea of the eight-hour-day seem very "radical," and this lessened popular support for the organized labor movement.

As the power of the Knights of Labor declined, the American Federation of Labor rose to the top. Under the leadership of Samuel Gompers, the A F of L tried to reform the length of the work day and child labor laws, and also tried to protect the independence and rights of other existing unions.

The Attitude of Early Labor Unions

Early labor unions were an exclusive group. At that time, most Americans were Western European in heritage. When Catholics from Italy, Ireland and Poland began to arrive in the early 1800s, they were often treated poorly by the majority white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants (W.A.S.P.) already here. Blacks, especially, were excluded from union membership. Ethnic and religious minorities often found assimilation into

American culture difficult.

Government's Treatment of Unions

Government leaders feared labor unions would disrupt business, and adversely affect the economy of the

United States. In 1895, the Supreme Court used the Sherman Anti-trust Act against unions, ruling that strikes were illegal because they interfered with interstate commerce. Both federal and state troops were used to stop strikes.

Following the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911, where 146 workers were killed, the government began to change its opinion. Public sympathy for workers grew, and as a result. Congress passed laws helpful to unions.

In 1913, Congress created the Department of Labor to help enforce labor laws, and study labor statistics.

The next year, Congress passed the Clayton Antitrust Act, which exempted unions from antitrust laws and federal injunctions, or court orders, prohibiting strikes.

Congress did not order an eight-hour day until 1933. Even then, the National Industrial Recovery Act was an emergency act taken by President Franklin Roosevelt to help counter the economic ruin caused by the Great

Depression. The Act defined maximum hours, minimum wages, and the right to collective bargaining. Struck down by the Supreme Court in May 1935, the Recovery Act was soon replaced by the Wagner Act, which assured workers the right to unionize.