Program Notes for April 26, 2014

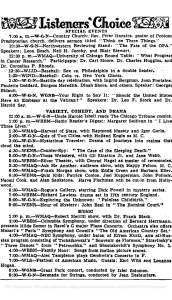

advertisement

Program Notes for April 26, 2014 By Ellen Schmidt Siegfried Idyll Richard Wagner (1813-1883) Though famed for his operas and the radical change he brought about in that art form, musical proclivity was not something Wagner evidenced as a child. He had no musical training at all before beginning piano lessons at the age of twelve. He never became truly proficient on any instrument. However, at the age of fifteen, after hearing Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, he decided to become a composer. Later he said that early in his life he knew that he would be great, but it took some time for him to discover what he would be great at. He had little training in music theory and composition; he was largely selftaught. He thought big and he believed in himself and the music he would create. He was an egotist who once said, “I am not made like other people. I must have beauty and brilliance and light. The world owes me what I need.” Music historian David Dubal states that the first complete performance of his huge Ring of the Nibelung at Bayreuth in August of 1876 “was the single greatest and most publicized artistic event of the nineteenth century. It put the final stamp on Wagner as the supreme artistic force of the age. He became, after Napoleon, the most written-about person of the nineteenth century.” Siegfried Idyll is one of the few works Wagner wrote for instruments alone. An idyll is a musical work intended to evoke rustic life. In 1864, King Ludwig of Bavaria, an ardent Wagner fan, invited him to stay at a royal villa. Wagner brought with him the conductor and pianist Hans von Bulow to help him make music for the king. Von Bulow was accompanied by his wife, Cosima, daughter of Franz Lizst, with whom Wagner immediately began an affair. At that time he sketched a movement of a string quartet which he never completed, though he did use some of the material from it in his opera (or “music drama,” as he called it) Siegfried, one of the four operas in the Ring cycle, which he composed in 1869. At that time he and Cosima had become parents of three children, two girls and a boy named Siegfried, born in 1869. For Cosima’s 33rd birthday, in 1870, Wagner composed Siegfried Idyll as her gift. It was performed by fifteen musicians at their Villa Tribschen that morning. Cosima wrote in her diary: “As I awoke, my ear caught a sound, which swelled fuller and fuller; no longer could I imagine myself to be dreaming. Music was sounding, and such music! When it died away, Richard came into my room with the children and offered me the score of the symphonic poem. I was in tears, but so was all the rest of the household. Richard had placed his orchestra on the staircase, and thus was our Tribschen consecrated forever.” The children called it the “Staircase Music.” The manuscript was kept as a family memento until financial difficulties forced them to sell it to a publisher in 1877. Music annotator Denby Richards writes: “The string quartet music of 1864 forms the basis of the work, which incorporates as well music from Siegfried related to the love of Siegfried and Brunnhilde, and a little lullaby (played by the oboe) which Wagner had noted down two years earlier.” Wagner himself published a detailed program for the piece which states that it is about a mother singing her infant son to sleep and her vision of the man he will become. Though it was played by only a few instruments at Tribschen, Wagner intended it to be performed by a larger orchestra and often conducted it at orchestral concerts later on. Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 22 Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880) Wieniawski was born in Lublin, Poland, which was then part of Czarist Russia. His mother was a professional pianist and the family hosted many musical guests and activities. Henryk’s musical gift was recognized when he was quite young, and he began violin lessons at five. He progressed rapidly and by the age of seven he was performing in quartets and playing concerti at musical gatherings in their home. When he was eight, his mother took him to Paris to audition for the Conservatoire, where he was admitted despite the fact that he was too young and not French. He graduated when he was just eleven, winning the first prize in violin performance, though he continued lessons with his teacher for two more years. At thirteen, he began his career as a concert violinist, performing first in Paris and then in St. Petersburg, before returning to the Conservatoire in 1849 to study harmony and composition. He received his diploma in composition at fifteen. Between 1851 and 1853 he gave over 200 recitals, often accompanied by his brother Jozef, a pianist, who was two years younger. At the same time he composed fourteen violin pieces, including his first concerto, which were meant to showcase his virtuosity. From 1860 until 1872, Wieniawski lived in St. Petersburg. He was soloist for the czar and the court theater, leader of the string quartet of the Russian Music Society, and a teacher at the new St. Petersburg Conservatory. He then spent two years concertizing in the United States with Anton Rubenstein as his accompanist. Rubenstein commented that “He is without doubt the first violinist of our time – there is no one comparable.” After a brief period teaching at the Brussels Conservatory, Wieniawski resumed his travels. Music historian Harold Schoenberg writes that “Wieniawski conquered the public wherever he went – Paris, Vienna, Prague, Budapest, Scandinavia, London, and of course his homeland, Poland.” By 1878 he had developed heart problems, and he died on March 31, 1880, while on tour in Moscow. Wieniawski’s Violin Concerto No. 2 was composed in St. Petersburg. It premiered on November 27, 1862, with the composer as soloist and Rubenstein conducting the Orchestra of the Russian Music Society. It was published in 1870 and dedicated to Wieniawski’s friend and fellow violin virtuoso, Pablo de Sarasate. Today it is a part of the standard repertoire for violinists around the world. The first movement, marked Allegro moderato, opens with the orchestra presenting both themes, the first by the strings and the second almost immediately by the solo horn. The orchestra expands on these before the solo violin restates them and develops them further. The second movement is a beautiful Romance and the third a lively rondo in gypsy, or Hungarian, style. In today’s concert we will hear the first movement only. Symphony No. 101 in D “The Clock” Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Haydn is known as the Father of the Symphony, being credited with developing the symphony from the orchestral suite and the keyboard sonatas of C.P.E. Bach. Between 1759, when he composed his first symphony, and 1795, when he composed his last, Haydn composed 104 symphonies and, in the process, perfected the form of the classical symphony. David Ewen writes that “When Haydn started writing music, the symphony, sonata, and string quartet were in their infancy. It was due to Haydn that they were brought to full development.” Music historians Wallace Brockway and Herbert Weinstock state that “one and all, Haydn’s symphonies breathe his sunny disposition, his wit, his irrepressible high spirits, and his sane and healthy love of life. His best symphonies are canticles of life enjoyed to the full – works of lively beauty that rank just below the best of Mozart and Beethoven.” The symphony opens with a somber and mysterious Adagio in D minor and then jumps into the lively Presto in 6/8 time. Its two themes are quite similar, the first rising in pitch and the second moving downward. Both are developed extensively. It is the second movement, marked Andante, which gives the symphony its nickname of “The Clock.” The stately melody played by the violins is accompanied by pizzicato strings and staccato bassoons. Even in the stormy middle section in D minor the ticking continues. The serenity of the opening section returns and the movement ends quietly. The rather pompous minuet is the longest Haydn ever wrote. The equally lengthy trio section is a perfect example of Haydn’s musical wit. D. Kern Holoman writes that it gives “the impression of a sleepy village band, with its hurdy-gurdy drones and piped solo. None of it quite works: the relentless drones from time to time imply the wrong harmony; the flute solo is altogether pointless; the violins go on too long; and the horns at the end of the trio hang on to their cadence point even when it manifestly clashes with the rest of the chord structure.” The energetic finale is based largely on the simple theme which the violins present at the outset. Annotator Duncan Gillies writes that “In broad outline, the movement is a rondo, with two returns of the main theme. However, both of the intervening episodes use material taken from the main theme, giving the movement the character of a continuous development. A short coda brings the movement to a forceful conclusion.”