visible inequality leads to violent crime

advertisement

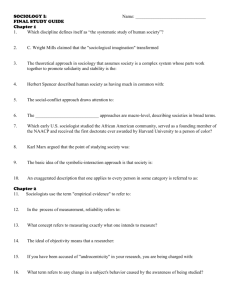

VISIBLE INEQUALITY LEADS TO VIOLENT CRIME The visible consumption of luxury cars, jewellery, designer clothing and other status symbols leads to increases in violent crime. That is central finding of a study of consumption and crime in the United States over the past two decades, presented at the Royal Economic Society’s 2011 annual conference. The study by Daniel Hicks and Joan Hamory Hicks looks at the idea of ‘conspicuous consumption’, a phrase coined by the nineteenth century economist Thorstein Veblen to describe purchases of goods that display status and which make others feel unhappy or angry. Such visible consumption also sends a signal to potential criminals, informing them of the potential gains from crime. Examining variation within US states over two decades, the research documents a strong link between the distribution of visible consumption and violent criminal offences. Specifically, it finds that when the consumption of conspicuous goods in US states becomes more unequal, crime tends to rise. To show that the rise is caused not just by income inequality, the authors report that property crimes do not increase along with the sales of status symbols. They cannot pinpoint the precise cause of this finding, but conclude: ‘for whatever reason, it appears that the display of opulence appears to have a negative effect on the social fabric, increasing the degree to which neighbours are willing to harm one another.’ More… Why do people buy luxury cars, jewellery, designer clothing and oversized houses with manicured lawns? Economists tend to think they do so for two reasons. First, as with any other product, consumption of these goods tends to make people happier. Second, people may derive happiness from the status conveyed by these purchases. Nineteenth century economist Thorstein Veblen coined the term conspicuous consumption to describe purchases of goods to display status or gain honour. In addition to making individuals happy, these purchases have the added effect of making others around them unhappy. Research has shown that relative status – that is, acquiring goods of equal or higher quality than our neighbours – appears to matter for our own happiness. In other words, there is some truth to the age-old expression about ‘keeping up with the Joneses.’ One of the authors notes: ‘Purchasing goods and services that are highly visible sends a signal of your status. My wife was thrilled to receive an engagement ring several years ago. Nevertheless she removes the ring when she travels to major cities or parts of the world that are less safe. ‘This is because visible consumption also sends a signal to potential criminals. Specifically, it informs them of the potential gains to be had from partaking in criminal activity. ‘Worse yet, because as research has shown, relative status affects people’s happiness, it might also encourage them to become disenfranchised or angry with society.’ The analysis examines the relationship between social inequality and criminal activity. When there is inequality in socio-economic status that is visibly stark, what is the implication for the level of crime? Previous research on economic inequality and crime has focused on inequality in income, in spite of the fact that income is not directly observable within a community. Instead of focusing on income inequality, this study directly examines the level of visible inequality – inequality in consumption behaviour. Examining variation within US states over nearly two decades, it documents a robust association between the distribution of visible consumption and violent criminal offences. Specifically, it finds that when the amount of consumption of conspicuous goods in US states becomes more unequal crime tends to rise. The analysis examines specific types of both violent and property crime. One would expect to see property crime, particularly activities like theft, increase in response to inequality in visible consumption if such purchases informed criminals of the potential benefits of their activities. Surprisingly, there is no evidence that this is the case. Instead, violent crime, and in particular assaults, rise when visible consumption becomes more unequal. This finding is more consistent with social theories that connect violent crime with relative deprivation than with economic theories about information or opportunity cost to crime. Although the research cannot determine the exact channel, for whatever reason, it appears that the display of opulence appears to have a negative effect on the social fabric, increasing the degree to which neighbours are willing to harm one another. ENDS ‘Jealous of the Joneses: Conspicuous Consumption, Inequality, and Crime’ by Daniel Hicks and Joan Hamory Hicks