ex - Louisiana State University

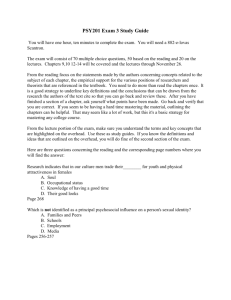

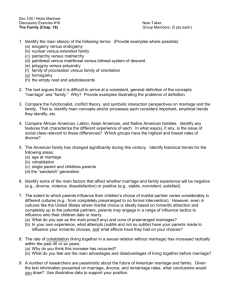

advertisement