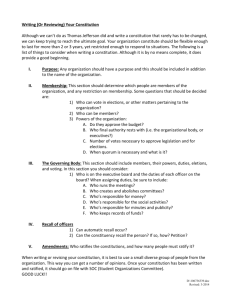

Towards the Elections

advertisement