Brock University Emergency Medical Response Plan

advertisement

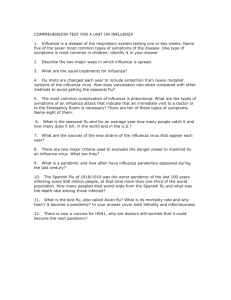

1 Brock University A Discussion Paper On Medical Emergency Response Planning Created: April 1, 2007 Brock University’s Medical Emergency Response Plan (MERP), an annex to the University’s Emergency Response Plan, describes the steps the University will take to respond effectively to a medical emergency. In particular, the MERP states how our key administrative areas will respond to the effects of a highly contagious disease such as pandemic influenza that could affect operations over a period of time longer than that for which the procedures of the more general Emergency Response Plan are intended. This Discussion Paper provides the rationale for the detailed action plans to be followed by each administrative area and serves to inform the University community about what decisions will be made, and why, in the event of a medical emergency such as pandemic influenza. Summary Brock University’s Medical Emergency Response Plan will be implemented if and only if The President of the University, or his designate, chooses to declare a University medical emergency in response to: (a) The Niagara Region Medical Officer of Health formally identifying a medical emergency (such as, but not limited to, pandemic influenza) in the Niagara Region, or (b) The Brock University Medical Director, upon consulting with the Director of Clinical Services and with the Niagara Region Chief Medical Officer of Health, formally advising the President that our campus is experiencing a medical situation that requires the Medical Emergency Response Plan to be implemented. In the absence of a formal declaration of a Medical Emergency, the operations of the University will continue under the auspices of approved policies and procedures as exist at a particular time. The effect of implementing the Medical Emergency Response Plan will be to: 2 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Suspend immediately all instruction in all courses Suspend all student extracurricular activities Suspend immediately all University-Community activities and events Evacuate immediately University Residences Suspend immediately all University Committee activity except the Board Executive Committee and the MERP Crisis Management Group 6. Maintain the University’s research activities within guidelines provided in the MERP to facilitate social distancing and infectious disease prevention 7. Maintain University operations in other areas as fully as possible based on plans implemented in each administrative area of responsibility When the medical emergency has ended, as determined by a formal pronouncement from the Niagara Region Chief Medical Officer of Health or on the formal advice of the Brock University Medical Director, the President of the University, or his designate, shall announce the resumption of all suspended activities and each area of campus shall, according to its area-specific plan, restore its operations to normal conditions as quickly as possible. NOTE: It is the intention of this plan to include both St Catharines and Hamilton campuses in its purview. Thus, any decision taken to implement the MERP will have effect at both campuses simultaneously. It is, in theory, possible that a declaration of a medical emergency could be made by the Chief Medical Officer of Health responsible for Hamilton without one being made by the Chief Medical Officer of Health in Niagara, In such circumstances, unlikely though they might be, it shall be at the President’s discretion whether to close the Hamilton campus while not closing the St Catharines campus and to determine the constraints on university activity that typically involve students, staff, and/or faculty who may be engaged in activities on both campuses during an affected semester. Why Has The University Created A Medical Emergency Response Plan (MERP)? The potential outbreak of influenza on a global scale and the possible catastrophic consequences of such a pandemic have been very much in the public eye since 2005. At that time, international health authorities began expressing concern that a particular virus that infects domestic poultry and migratory wild fowl had also infected humans who had come in contact with diseased birds. The strain of virus, known as H5N1 (for the particular combination of proteins comprising the coat of the virus), was especially virulent and a very high percentage of those few human cases reported had died. Further raising concern was the rapid spread of this “bird flu” from its origins in Asia, through the Middle and Near East, to Europe. At the time of the approval of our MERP, the virus was not one for which there existed evidence for transmission from human to human. There had only ever 3 been evidence of the virus being transmitted by direct human contact with the saliva, nasal secretions, or feces of infected birds. If the virus were to mutate to become one transmissible from human to human, this would result in the conditions that typically result in a pandemic spread of a disease. This is what happened in the global influenza epidemics of 1968, 1957, and 1918 (during which 20 million people died worldwide). In the event of pandemic influenza, we would be faced with the introduction of a new and highly contagious virus that causes serious illness or death and for which the human population has little or no immunity. Of particular importance to a University community, the current “bird flu” has, like the Spanish flu of 1918, been especially deadly to young people, potentially including the age group typically found on our campuses. Highly virulent influenza is dangerous enough: to find that we might face the prospect of a strain that preferentially attacks those who make up the vast majority of our community’s population is especially sobering and provided a powerful impetus to plan accordingly even though there was no clear and immediate threat of a pandemic at the time our plan was created. Influenza pandemics – worldwide outbreaks – have historically arisen about every 30 years and occur when all four of the following conditions arise: 1. A new influenza A virus appears and the human population has no or little immunity, resulting in several, simultaneous epidemics worldwide with enormous numbers of death and illness. 2. Human-to-human transmission happens easily. With the increase in global transportation and communications, as well as urbanization and overcrowded conditions, epidemics of a new influenza virus are likely to spread quickly around the world. 3. The new virus cause serious clinical illness and death. Outbreaks of influenza in animals, especially when happening simultaneously with outbreaks in human, increase the chance of a pandemic, through the merging of animal and human viruses. 4. The population has little or no immunity to the virus. A vaccine will not be available at the start of the pandemic as the virus will be new. Strains of influenza vary over the years due to changing protein structure of the viral coat, making vaccine production difficult. Attack rates have historically been about 20 - 40%. Of these, about 50% require outpatient care; about 20% require inpatient care and 1-5 % die. Considering our Brock numbers of approximately 17,000 students, assuming our campus were to be affected as the more general population considered by those who model outcomes, our worst case scenario would be over 4000 ill (1000 in residence), at least 2000 students requiring formal outpatient care from our campus health services or elsewhere, and as many as 75 students dying. If the attack rate were half the worst case scenario, that would mean we would have 2000 Brock students’ sick (500 in residence), 4 1000 students requiring formal outpatient care, and still as many as 35-40 deaths. Influenza virus is contagious 24 hours before symptoms. It is spread by droplet transmission and its droplets can survive 24 –48 hours on hard surfaces, 12 hours on cloth, paper or tissue and 5 minutes on hands. Incubation is 1-3 days. Influenza patients are contagious for 7 days, beginning one day before the onset of symptoms. A specific concern with infections such as “bird flu” is that students with such cases of influenza could become severely ill within one day and many students live in close proximity to each other in residence settings. This creates the possibility of rapid spread. Those with influenza virus when already affected by other medical conditions may be more susceptible to other illnesses. Many possible medical emergencies could unfold on our campus, run their courses, and our responses to them would be a single process of limited duration, not requiring formal and long term intervention such as anticipated in the MERP. To reiterate, not all emergencies of a medical nature will necessitate the implementation of this Medical Emergency Response Plan. However, it is likely that an infectious disease such as a pandemic influenza would affect us in waves separated by perhaps 6-9 months. Past experience suggests that the second (or even a third) wave of such influenza would have greater impact on public health than the first wave. In our planning, we must be prepared for the medical impact of such a disease to affect the campus across more than a single academic year. We must be prepared to learn from experience and adapt to the lessons that earlier waves of a pandemic would provide. Why plan in the absence of a certain threat? The potential numbers alone are compelling reason to do all that we can do to address the potential problem before it arrives. We found on a much smaller scale with SARS and later with the devastating effects of Hurricane Katrina on the city of New Orleans (and its Universities) that the midst of a crisis or emergency is not the time to be planning what to do in response. The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago. The second best time is now. So, we undertook to create a plan well in advance to deal with circumstances that we hope do not ever come to pass. On advice from health authorities internationally (World Health Organization), the Government of Canada (through the Canadian Public Health Agency), the Government of Ontario (through its Ministry of Health), and the Region of Niagara (through the Niagara Region Public Health Department), Brock University has prepared this plan to allow us to respond as effectively as possible to a medical emergency including, but not limited to, pandemic influenza. 5 What Are The Principles Upon Which The Creation And Implementation Of Brock’s Medical Emergency Response Plan Are Built? The foundation of our Plan is an ethical one. In times of crisis or emergency, it is imperative to have stated principles that guide the decision making of all those whose task it will be to steer the University through a medical emergency. During and after the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome or “SARS” in Ontario health care facilities in 2003, the University of Toronto Centre For Bioethics published a document describing the ethical basis for decision-making in response to a medical emergency. Brock University has adapted and adopted their guidelines as the basis for its planning process and for the implementation of the MERP should it become necessary. Our commitment is to adhere to this ethical base by enshrining it here to assist with decisions that will have to be made in the event of a medical emergency. 1. Individual Liberty and the Protection of the Public from Harm In a medical emergency, restrictions to individual liberty may be necessary to protect members of the University community from serious medical harm. However, restrictions to individual liberty should be proportional, necessary and relevant; should employ the least restrictive means possible; and, should be applied fairly. Decision makers should weigh the imperative for compliance, and provide reasons with their decisions to encourage compliance. 2. Stewardship and Accountability Decisions should be made by people who are credible and accountable as stewards of the University during a time of crisis. This implies that their decisions are intended to achieve the best health and academic outcomes given the unique circumstances of a medical emergency. Those authorized to act on behalf of the University community during a medical emergency must be able to act in accordance with the authority they have been given. However, there must be a process to review decisions (in light of the stewardship mission) when emergency conditions subside and reflection upon our handling of the medical emergency is possible. 3. Reciprocity and Professional Responsibility Measures to protect the public good during a medical emergency are likely to impose a disproportionate professional burden on a small group of key individuals. It is also understood that those entrusted with such responsibilities will have to weigh demands of their professional roles against other competing obligations to their own health, and to family and friends. Reciprocity requires that the Brock community support those who face these extraordinary burdens in protecting our health and well being during a medical emergency and take steps to minimize their burdens as much as possible. 6 4. Privacy Individuals have a right to privacy. In a medical emergency, however, it may be necessary to override this right to protect the Brock community from serious harm. Any such decisions will be taken in accordance with all applicable legislation governing protection of privacy. 5. Equity All those who are ill have an equal claim to receive the care they need under normal conditions. However, during a pandemic or other form of medical emergency on campus, difficult decisions will need to be made about which services to maintain and which to defer. Depending on the severity of the medical emergency, this could limit the provision of emergency or necessary services to some or all of our community. 6. Trust and Transparency Decisions should be based on reasons (i.e., evidence, principles, and values) that stakeholders can agree are relevant to meeting our needs in a medical emergency. Trust is an essential component of the relationships among all involved in a medical emergency. Decision makers will be confronted with the challenge of maintaining stakeholder trust while simultaneously implementing various control measures during an evolving health crisis. Trust is enhanced by striving for transparency of process in all respects at all times. 7. Solidarity A medical emergency at our University may require a new vision of solidarity with others beyond our own campus. A pandemic or other form of medical emergency can challenge conventional ideas of autonomy, security, or territoriality. This calls for collaborative approaches that may require us to set aside our self-interest in order to work with others . 1 Modified from original documentation at http://www.utoronto.ca/jcb/home/news_pandemic.htm What Preventative Steps Will We Take As Standard Procedure That Reflect The Concerns Of The Medical Community With Respect To Infectious Disease? In the process of planning for a possible medical emergency, it became clear that as a campus community we could take four important steps that made good health sense even if there were no possible medical emergency for which to plan. 7 The most effective way to prevent the spread of infectious disease is to counteract its mode of transmission. Some diseases are vector-borne (transmitted by carriers such as mosquitoes or rats). Some are air-borne. And some, like influenza, are droplet-borne. In the case of droplet-borne transmission, the best precaution we can all take is hand washing. It is the most powerful tool in our preventative arsenal to stop the spread of diseases such as influenza. Though it is not strictly speaking a response to a medical emergency, our planning process resulted in the development of a proactive commitment to advocate for proper hand washing as a regular feature of everyone’s day on campus. Accordingly, hand washing stations installed in key locations on campus were identified as a vital feature of good campus health and a campaign to encourage their use (and the use of washroom hand washing facilities) will be launched at the start of each Fall semester of each academic year as part of the MERP. The responsibility for this campaign will rest annually with the Office of University Communications working in collaboration with Student Health Services and Human Resources who will provide content and advice on dissemination for greatest impact. Accompanying a vigorous commitment to hand washing is a second strategy that we know to be effective in preventing the spread of both air-borne and dropletborne infectious disease. When sick, stay home. Since we cannot facilitate the spread of disease if we do not come in contact with others, staying away from others when sick with a disease like influenza is not simply a courtesy. It is social obligation that is often overshadowed by our commitment to our work. Therefore, as with the campaign to encourage hand washing, at the start of each Fall semester of each academic year, we will undertake a campaign to encourage members of the Brock community to do the right thing and stay home when sick. Third, every member of the Brock community is encouraged to plan ahead individually for self and family. The steps we can all take to be ready for any emergency are simple but ones that few of us typically take the time to address. A medical emergency checklist that we advise everyone to consider seriously as his or her personal commitment to preparedness is provided as Appendix 1 of this document. Fourth, as an educational institution, knowledge is our mission. Accordingly, given that an issue such as pandemic influenza is one of interest and importance, it is appropriate that we ensure that members of our campus community have access to the best and most recent information about something that has its origins in academic disciplines in which we have expertise on our campus. Therefore, via both the Health Services (for students) and Human Resources (for faculty and staff) web home pages, there will always be a link to www.brocku.ca/pandemicplan that will be a permanent site to visit to learn about medical emergency issues of relevance and interest to the campus. This information will be updated regularly and serve to balance the uncertainty and fear that can arise when speculation and rumour abound. In this document, 8 Appendix 2 presents some basic information about influenza that is of value to everyone in managing his or her health each year during cold and flu season. How Will We Monitor The Status Of Campus Health? The impetus for the development of this plan was the growing concern for a possible outbreak of pandemic influenza. However, this plan also anticipates other possible medical emergencies not related to pandemic influenza, particularly other forms of highly contagious infectious disease. A key element of our plan is to know when to implement it and that means knowing what levels and kinds of illness we are experiencing at any given time. To assist the University’s Medical Director in determining whether to advise the President to declare a medical emergency and to be able to provide Public Health officials with accurate information about Brock’s medical circumstances, the University will engage in an ongoing process of monitoring of illness among the Brock community. This will be done by: (a) Regular and ongoing monitoring of clinic visits to Campus Health Services by our Student Health Services staff, and (b) Regular and ongoing monitoring of information available from academic and administrative departments about student, staff, and faculty absence due to illness. These sources of data will be assessed regularly, and more frequently as needed in the event of perceived increased levels of illness on campus, by the Director of Clinical Services who shall be responsible for interpreting the various sources of information about campus illness levels. Via the Student Health Services and Human Resources websites, the University community will be informed of any significant increases in the level of campus illness. This will allow us to remind the community of our regular preventative measures and to promote healthy responses to circumstances in which ill health may be more prevalent. The University, via the Director of Clinical Services, will maintain regular communication with Regional and Provincial Public Health officials with respect to rates of illness at Brock and in Niagara and Ontario. This will allow the University to ensure that its sense of health and illness on campus is credible and reliable and that a decision to declare a medical emergency, either by the University’s Medical Director or Niagara Region Public Health officials, is a responsible and well-informed one. 9 Under What Circumstances Would The Medical Emergency Response Plan Be Implemented? The University operates on a daily basis with some of its students, staff, and faculty ill. At times, rates of illness can be high, particularly when we are in what is typically called “cold and flu season”. It is not the intent of the MERP to be implemented under such “normal” circumstances. Nor is it the intent of the MERP to be implemented on a partial basis to address challenging, but not emergency, medical conditions. Unless a medical emergency is declared formally as described in our plan, the University will continue to operate under the auspices of its approved policies and procedures, even with some of its members sick, and individual areas of administrative and academic responsibility will maintain as close to usual operations as possible. A benefit of engaging in the Medical Emergency Planning process is the awareness that has developed that each area, academic or administrative, must have a plan for business continuity whether that be in the face of a formally declared emergency or not. By virtue of our having contemplated the worst case scenario, we will have come to understand better the need to be prepared to manage key aspects of the University’s operations under circumstances in which leadership structures are jeopardized by illness or absence or for other reasons. Each area on campus, having planned for how it will deal with the kind of Medical Emergency envisioned in this document, should also have come to understand more fully who its key people are, how deep the skills needed extend into the work force of the area, what the key operational elements are for the area, and how these will be maintained even under major reductions in human resources. A medical emergency that requires the implementation of our MERP is different from campus life affected by normal, or even higher than normal, levels of illness. Rather than attempt to determine what an emergency is in formulaic terms (e.g., when illness levels reach a certain percentage of the student population or the work force), our MERP establishes the following process whereby a medical emergency is declared, causing the MERP to be implemented: The President of the University, or delegate if required, may declare a medical emergency, thus activating our Medical Emergency Response Plan, if and only if: (a) The Niagara Region Medical Officer of Health declares a medical emergency (such as, but not limited to, pandemic influenza) in the Niagara Region, or (b) The Brock University Medical Director, upon consulting with the Director of Clinical Services and with the Niagara Region Chief Medical Officer of Health, advises the President that our campus is experiencing a medical emergency that requires this plan to be implemented. 10 Our plan entrusts those most able to make the right judgment with respect to a medical emergency to declare formally that an emergency exists and to implement our plan. Who Is Responsible For Implementing Our Medical Emergency Response Plan? Immediately upon the declaration of a medical emergency by the President or delegate, the responsibility for the implementation of the Medical Emergency Response Plan will be assumed by the Crisis Management Group of the University as defined in the Emergency Management Plan (EMP). This group shall add as full members, for the purpose of our response to a medical emergency, the University’s Medical Director and Director of Clinical Services. Specifically, that group for the purpose of the MERP shall be comprised of: The President of the University The Vice-presidents of the University The University Medical Director The Director of Clinical Services, Student Health Services The Associate Vice-President, Student Services The Executive Director, Human Resources The Chief Information Officer The Director, University Communications The Executive Director, Facilities Management and the Director, Campus Security, will attend all meetings of the Crisis Management Group as per the Crisis Management Group regulations defined in the EMP. Other personnel may be added by the President in an advisory capacity as required. The Crisis Management Group shall convene for its first meeting in the Sankey Chamber and determine at that meeting where and on what schedule future meetings shall be held during a medical emergency. Will We Close The University If There Is A Medical Emergency? There is a remote possibility that the University could be required to close entirely. However, it is highly unlikely that any medical emergency, including pandemic influenza, would result in the complete closure of the University. This means that, even in the event of a formal declaration of pandemic influenza or other health-related challenge by the University and/or regional health authorities, we will not be required to abandon the campus completely and 11 enforce a complete suspension of all operations. Our Medical Emergency Response Plan assumes that, however great the challenge might be medically, the University will remain open and operational in many, though not necessarily all, of its functions. The key element of our plan is to enforce “social distancing”, that is, keeping people away from each other and out of large (and even medium or small) groups where infectious disease would more rapidly spread. However, though we will be obliged to take major steps to create the kind of social distancing that good public health practice demands, it is still not our intention to plan for complete University closure. The implication of taking this stance is that many facets of University operations would continue, at least at a maintenance level, even amidst a formally declared medical emergency. What Will Happen To Teaching and Learning During A Medical Emergency? If the University declares a medical emergency, thus implementing the MERP, there will be an immediate suspension of all instruction in all courses, undergraduate and graduate. All classes of all kinds (including, lectures, seminars, labs, workshops, lab meetings for teaching purposes) will be suspended for the duration of the declared medical emergency. All forms of assessment, including examinations and submission of essays or projects, are included in this suspension of activity. This is a very difficult step for a University to take. Teaching and learning are our core activities and a primary raison d’etre for any postsecondary institution. However, having established that our primary concern in this plan is the protection of the health of our community members, the need to prevent the spread of infectious disease must take precedence over our academic mission. The suspension of all instruction applies to all instructors and all students in all courses. While it might be desirable to attempt to continue instruction using alternative methods during a medical emergency, such methods would not be available to all students. If circumstances are sufficiently grave to warrant the declaration of a medical emergency, it is our belief that in terms of equity and clarity, it is preferable that we all pull together in a unified response and then adapt accordingly after the fact as a community rather than attempting piecemeal solutions that differ, during and after the medical emergency, in their processes, results, and implications. 12 How Will Students Be Affected Academically By A Suspension Of Instruction During A Medical Emergency? The Senate of the University has established 12 weeks, or 36 hours, as the minimum amount of formal instruction that a student should undertake in order to be eligible to receive a semester-course academic credit. These required hours may, in fact, be more in some courses that have laboratories, workshops, studios, or seminars in addition to three hours of lecture. Whatever the amount of instructional and assessment time required under normal circumstances, if we declare a medical emergency, for example under conditions of pandemic influenza, it will be the case that considerable instructional time may be lost and that normal assessment procedures (including a normal final examination period) will be significantly affected. It is impossible to prepare a precise plan for every possible contingency for a medical emergency such as pandemic influenza. We cannot know in advance how many waves of the pandemic might strike Niagara and Brock. We cannot know how long each wave will last. However, we can state the principles on which we will base our response to the need to suspend instruction. 1. Fall and Winter semester courses have priority over all other scheduled activities on campus. All other demands on university physical resources (such as classrooms, labs, recreational facilities, and residences) will have lower priority in the aftermath of a medical emergency than the need to assign time and space to instruction needed to complete as fully as possible Fall and Winter courses. This means that Spring and Summer courses will be scheduled only when Fall and Winter semester needs have been accommodated. It means also that conferences and community events (e.g., those that typically dominate the summer scene on campus) will be held only if time and space is available once Fall and Winter semester course completion needs have been met. 2. The President of the University, acting with the advice of the Vicepresident Academic, the Deans, and the Senate, will determine when sufficient instruction and assessment time has been provided to declare that students shall be awarded credits for which they enrolled in a semester suspended by a medical emergency. What Will Happen To Students Living In Residence During A Medical Emergency? If the University declares a medical emergency, thus implementing the MERP, we will take immediate steps to suspend our residence operations and require 13 students living in residence to leave the campus within 48 hours until such time as the declaration of the medical emergency is rescinded. The contractual arrangements made by the University with student residents will reflect the possibility of this occurring and Residence Services will communicate its evacuation plans clearly in its orientation program each year. While the University will not be responsible for the cost of students who are required to leave the campus, Residence Services will provide assistance and support in this, including: Advising on travel arrangements for students requiring assistance Providing standard move-out assistance as would normally occur at the end of the Winter term each year Collaborating with Student Health Services to provide temporary care in cases where a student may be too ill to travel immediately Collaborating with Brock International to provide assistance to international students whose circumstances may not allow them to leave Canada and return home for the duration of the medical emergency Collaborating with Counseling Services and other relevant areas within Student Services where necessary to provide assistance to other students whose circumstances may not allow them to return home for the duration of the medical emergency It is possible that the University will need to maintain a small ongoing residence operation for at least part of a formally declared Medical Emergency. This will require careful collaboration among Residence Services, Food Services, and Facilities Management to allow for those who might not be able to depart from the campus within the 48-hour period envisioned in the MERP. Each of these areas’ plans will reflect this collaboration. In the case of pandemic influenza, the University will likely be one of a number of designated “Flu Centre” sites for the Niagara Region and that makes our duty of care considerably simpler than if we were to be responsible for our students ourselves. The resources for such Flu Centres would be provided by the Region, including health care staff. In the event of a declared medical emergency and the subsequent evacuation of residences, students who might have already become too ill to travel would be cared for on campus in its capacity as a Flu Centre until such time as they were healthy enough to be released. Nevertheless, the University must still plan for the maintenance of a small residential facility for students released after treatment and others not able to travel immediately in the event of a residence evacuation. 14 What Will Happen To Student Extracurricular Activities During A Medical Emergency? In the event of a medical emergency being declared and the MERP being implemented, all student extracurricular activities shall be suspended immediately. This includes intercollegiate athletics, including competitions hosting Brock athletes at other campuses; campus recreation; any activities taking place in The Zone and the University Aquatics Centre, as examples, which shall be closed until the end of the medical emergency; and any other student activities that require groups to congregate on or off campus under the auspices of the University. What Will Happen To Scholarly Research During A Medical Emergency? Each researcher will decide if and how he or she will continue to engage in scholarly activity during a declared medical emergency. However, each member of the research community must adhere to the requirements governing the maintenance of research activity on campus as follows. 1. It is highly desirable that faculty research continue as normally as possible. Where faculty research is primarily an individual enterprise and not dependent upon specialized University facilities, faculty should work from off campus as much as possible and minimize time spent on campus in contact with others. 2. Where faculty research, either individually or in teams, depends upon specialized University facilities such as laboratories, library, animal care facilities, or on-campus information technology resources, faculty should attempt to limit their time spent on campus as much as possible, recognizing that they will wish to avoid the loss of any time- or environment-sensitive research enterprises (e.g., biological cultures, experiments already in progress whose successful completion requires the maintenance of a previously organized schedule). Faculty conducting such research and intending to be on campus must inform the Associate Vice-president Research in writing of their intentions, with copy to the Dean of the relevant Faculty, explaining the nature of the research that requires an on-campus presence, and providing an estimate of the amount of time on campus that is needed to ensure that research in progress is not lost. The possibility of continuing research in University facilities assumes safe operating conditions. If these are not present, as determined by the Associate Vice-president Research in consultation with the Executive Director of Facilities Management and the Dean of the 15 3. 4. 5. 6. relevant Faculty, even the most important research will have to be suspended. The University is home to a broad range of sensitive and expensive research equipment that requires regular attention if it is to remain functional. Each researcher, in his or her laboratory environment, will be responsible for determining whether or not equipment can be maintained operational or whether, in the face of uncertain working conditions, should be shut down according to standard operating procedures. Where research equipment is not the sole responsibility of a single person, user groups must decide who will take responsibility for such shut down procedures and take action accordingly. Such decisions must be made locally by those most able to make them. Where indecision occurs, Department Chairs and, if necessary, the Dean of the Faculty shall be responsible for ensuring that the University’s equipment resource is managed effectively during a Medical Emergency. The University’s Animal Care Facility is a unique environment with considerable duty of care as per federal regulations and Brock policies and procedures. In the event of a Medical Emergency, there must be provision made for the continuing ethical treatment of all animals under our care. The University’s Animal Care Committee must have a plan in place to provide care to animals in its facility in the event that those normally responsible are unable to work due to illness. Graduate students, like faculty, often have research projects that should, if at all possible, be maintained. Therefore, if they choose to do so, graduates students may attempt to maintain thesis-related research where possible but do so in a way that minimizes even small groups from working together in confined laboratory or other research spaces. While graduate students may, like faculty, attempt to maintain their research programs under the terms of the Medical Emergency Response Plan, graduate courses may not continue formally or informally during the declaration of a medical emergency. Also, while some individual research activities many continue, research team meetings, workshops, and gatherings even in small groups that are not vital to the maintenance of a particular research project must be discontinued for the duration of the declared emergency. Undergraduate students will not be permitted to be involved in on-campus research during any period in which instruction has been suspended since the primary goal is to limit the number of people on campus and to prevent interactions that might facilitate the spreading of infectious disease. When either an internal or external declaration of a medical emergency (such as pandemic influenza) is made, faculty must postpone immediately all on-campus human subjects research until such time as the declaration is rescinded. With the permission of the Vice-president Academic, human subjects research that takes place in field conditions off campus may be allowed to continue as long as that research does not take place in an area in which there has been a declaration of a medical emergency (such 16 as pandemic influenza). For example, if the entire Niagara Region were to be declared by Niagara Region Public Health as an area in which there was pandemic influenza, no human subjects research would be permitted anywhere in the Niagara Region. However, faculty conducting human subjects research farther afield (perhaps out of the country) where no such medical emergency exists, would be allowed to pursue those research activities. How Will Our Administrative Operations Continue During A Medical Emergency? The details of how each administrative and academic area of responsibility will manage at least maintenance levels of operation are specified in specific Appendices of the Medical Emergency Response Plan. Each of these plans adheres to these principles: 1. All meetings of University committees, formal or informal, will be postponed immediately in the event of an internal or external declaration of a medical emergency. This includes all meetings, however small, that require visitors from off campus to come to campus. The only exceptions to this are the convening of the senior management team, chaired by the President of the University, to administer the Medical Emergency Response Plan and the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees. 2. The first priority of this plan is to safeguard the health of individual members of our University community. Therefore, it is desirable in each area of administrative responsibility to maintain operations as fully as possible but only in ways that emphasize during a declared medical emergency social distancing and other effective public health practices. 3. Where possible, administrative areas should have methods to maintain essential operations from off campus locations. A University is a community and it is not in any way desirable to have the members of that community dispersed and unable to interact in the usual way that a collegial and collaborative organization works best. Therefore, these dispersed operations are not intended in any way to be normal practices but rather to serve the University’s needs only during a declared medical emergency. 4. The University remains committed at all times to providing a safe place to work for all its staff and faculty. The declaration of a medical emergency, such as pandemic influenza, does not, a priori, mean that the University has become an unsafe place to work. However, it does mean that the University must become a place of even higher vigilance around sound public health practices and even greater commitment to information to all who will be on campus during the declared emergency. 17 How Will We Communicate With Each Other During A Medical Emergency? Daily communication, both within the University and with community members and partners outside the University, is an essential component of the MERP. To that end, our entire current communications strategy assumes that externally provided telecommunications services will remain intact on a day by day basis. We assume we can rely on standard landline and cell phone networks to provide us with access to each other and to agencies outside the University. Similarly, we assume that externally provided internet infrastructure will be available to which our own servers can connect to provide access to the world at large to send and receive e-mail and to access public health websites for up to date information. If these assumptions can be extended into a period of prolonged Medical Emergency, Information Technology Services will, through its plan, provide sufficient redundancy in its provision for external connectivity that at least emergency communications via one provider or another will be maintained at all times. Included in our communications plan is the adoption of a Blackberry strategy that will link all of the University’s senior administrators to each other and to all other Blackberry users worldwide. This particular form of wireless connectivity will provide a layer of information sharing internally and externally that will complement standard telephone, e-mail, and web services. The greater the redundancy in our planning, the greater the likelihood that something at least resembling normal electronic communications will be possible. Under such conditions, during a medical emergency, the role of the Manager, Telecommunications and Network Services will be a key one. Information Technology Services will ensure in its staffing plan for a medical emergency that this role will be continuously filled. In the event of a breakdown in telecommunications systems internally or externally, or both – a scenario taken seriously by those engaged in Pandemic Planning – the Crisis Management Team must have a pre-arranged way of communicating that does not rely on electronic systems. This will inevitably require face to face meetings and must be set up ahead of time and used accordingly if the time arises when it is necessary. Similarly, the Office of University Communications, as part of its area plan, must have a pre-arranged way of gathering and disseminating information as effectively as possible and , particularly, communicating with Public Health authorities on at least a daily basis. How Will We Maintain The Physical Resources Of The 18 University During A Medical Emergency? There is considerable cross training with the current Maintenance and Operations Staff in Facilities Management, supplemented by lead hands. This would ensure that day to day supervision could continue in the event of a medical emergency. Items not considered to be day to day requirements would continue as possible on a reduced-service basis to allow the focus to be on vital, day to day operations. With respect to trades, basic levels of service would be maintained during staffing shortfalls as long as at least half of the normal staff were available to work. In some key areas (e.g., control mechanics and refrigeration) staffing levels are low to begin with so illness in these areas might require supplementation from outside contractors in order to meet even basis service provision requirements. Depending on the time of year, certain priorities would have to be set for safety reasons (e.g., snow plowing in winter). Also, fire safety could become a critical issue if maintenance became compromised and so resources would have to be devoted as needed to meet the expectations of the University’s Fire Plan (e.g., inspection protocols). What Health Care Services Will Be Available During A Medical Emergency? Student Health Services (SHS) already has considerable experience in planning and implementing a strategy to manage seasonal influenza outbreaks on campus. This strategy will be expanded in the event of a medical emergency involving highly contagious infectious disease such as pandemic influenza. SHS is staffed with many part time staff who have other health related jobs (e.g., hospital nurses in critical care). In the case of pandemic influenza, our SHS could be operating with 30–50 % fewer staff while trying to handle three to four times the patient load. To combat this primary care challenge, SHS’s plan includes provision to gain access to those with various health care skill levels who could contribute to primary care (e.g., Nursing students). Also, SHS will integrate their operations with the community medical care sites according to provincial protocols available at the time of a medical emergency. SHS has a good working relationship with the Niagara Regional Public Health Department as well as the Niagara Health System and will be in daily contact with these two health care systems to optimize collective local resources. Maintaining these relationships is imperative and the University should strive at all times through all of its relevant officers to ensure the communication regionally is strong and clear. Student Health Services will modify their procedures during a medical emergency to ensure optimal care. Waiting room procedures will provide: 19 Signage on the door prominently directing students to STOP and complete their medical information A hand washing station at the entrance Kleenex in waiting area and receptacles for their disposal An area for triage if that becomes necessary Masks for incoming students SHS will require patients to provide medical information to assist staff in identifying influenza-like illness (ILI). Administrative staff will check each patient’s information and if two or more of the criteria are present in the self report, then staff will follow the administrative protocol for ILI patients as determined at the time of the medical emergency by provincial government policy. SHS is committed to providing medical assessment and education to as many patients per day as possible. However, they will be limited in their ability to handle patients requiring further treatment such as IV fluids, oxygen, and antibiotics. Protocols have been prepared for increasing numbers of ILI patients presenting to SHS daily. The maximum capacity for such patients would be 15 per day. These protocols are based on droplet precautions, separating ILI and non ILI patients, appropriate triage, flexibility on operations, selective cancellation of non essential bookings, protection of medical and administrative staff, use of ancillary facilities, and recruitment of extra personnel. Significant numbers of additional people whose level of duties would be based on skills sets, (e.g., monitoring of sick patients and residence students: education: preparing self-care packages: computer help) will be needed and SHS will collaborate with the Department of Nursing and other units in the Faculty of Applied Health Sciences to help to fill this need. SHS will also seek out other university responders as needed. It is expected that SHS will need to redirect many of their mental health patients to alternate care (e.g., student counseling). Due to the magnitude of a medical emergency such as pandemic influenza, care provided by the medical system outside the University will be primarily home based care. Therefore, students will be expected to seek care from their family physicians in their home locations. The evacuation of residences will further emphasize this approach. For any students requiring care on campus during a state of medical emergency, SHS will coordinate monitoring and care of these students in collaboration with other campus services (e.g., Residence and Food Services). How Will We Restore Operations When An End To A Medical Emergency Is Declared? 20 There will come a time when the severity of the medical emergency and the danger posed to the public health of the Brock community will diminish and the Crisis Management Group will be able to consider a restoration of normal University life. At that time, upon a pronouncement from the Niagara Region Chief Medical Officer of Health or on the advice of the Brock University Medical Director, the President of the University shall announce the resumption of all suspended activities and each area of campus shall, according to its areaspecific plan, restore its operations to normal conditions as quickly as possible. This announcement will be transmitted to members of the University community in as many ways as possible, including an announcement on the University website home page, a broad based media campaign, and by collaborative efforts in each area of administrative responsibility to ensure that all members of the Brock Community are made aware of the change in status of the campus. There are few upsides to managing through a medical emergency. However, in the case of an emergency such as pandemic influenza, one thing will be our advantage. From the time of a formal declaration of a medical emergency, we will have time, perhaps 6-12 weeks, to refine our strategy for re-opening the University and restoring operations fully. Much of how we do this will depend on the time of year and the severity of disruption from which we will have to recover. It is not that our plan is to avoid up-front responsibility for being ready. It is that we recognize the opportunity that the emergency itself will offer to think carefully and with the fullness of all available information to make good decisions that we cannot make in advance. How Will We Ensure That We Stay Ready For A Medical Emergency? The Medical Emergency Response Planning process is an ongoing aspect of the University’s administrative readiness to respond to circumstances that could have a negative impact on our academic mission. It is necessary for the University to ensure that is stands ready at all times to take action as needed. The plan, therefore, addresses key elements that, taken collectively, describe our state of readiness to mitigate the negative effects on our academic mission by a medical emergency. Since there is always the possibility of a medical emergency disrupting our campus, quite apart from the recent focus on pandemic influenza, our plan includes provision that, each year, the Senior Administrative Council will review the Medical Emergency Response Plan and determine if it remains effectively in place and ready for implementation. 21 SAC will also communicate each year with the person responsible for each area of responsibility for which an area-specific appendix is included in the Plan and require that each area confirm that their area-specific plan remains functional. As a guideline for this annual review, each area of responsibility will use the following evaluative framework to determine if the MERP remains viable in each area of responsibility: A. Planning, Coordination, and Communication 1. Who comprises your area’s medical emergency response team and what defined roles and responsibilities for preparedness, response, and recovery planning does each person have? 2. How does your plan provide for accountability and responsibility as well as resources for implementing specific components of the plan? 3. What are the meaningful timelines, deliverables, and performance measures defined by your plan for maintaining operations during a medical emergency in which widespread illness affects our workforce? 4. How does your plan provide for different outbreak scenarios including variations in severity of illness, mode of transmission, and rates of infection in the community. 5. How does your plan address the need for “social distancing” to occur by providing for clear direction to those working in your area? 6. How does your plan provide for clear and reliable daily communication with al those who need to hear from you and from whom you need to hear? (B) Continuity of Operations 7. How does your plan provide for the possibility of the alternative procedures for operating in the event of disruption of normal operations due to a medical emergency? 8. How does your plan provide for the continuity of operations with respect to maintaining essential operations of the university in your area of responsibility? (C) Infection Control Procedures 9. How does your plan contribute to our need to limit the spread of infectious 22 disease such as influenza on campus? 10. How does your plan address employee absences due to unique to medical emergencies such as pandemic influenza? 11. How does your plan provide for case identification and the reporting of information about those in your area who are ill? 12. How does your plan identify the ways in which you might support a surge in demand for your services and establish steps to have the necessary resources on hand? 13. How does your plan establish how movement on campus and to and from campus will take place during a medical emergency such as influenza pandemic (e.g., with respect to voluntary and mandatory movement restrictions). (D) Post-emergency Procedures 14. How does your plan provide for a recovery strategy to deal with consequences of a medical emergency once it is over? 15. How does your plan provide for the resumption of normal operations when the medical emergency has been declared over? Each of the areas of responsibility will be evaluated in this way and categorized as either (A) In Place or (B) In Need of Action. Where an aspect of the plan is found to be in Need of Action, the Senior Administrative Council will assign one of its members, or delegate, to take the necessary steps that will allow the item in question to be re-assessed as being in place. 23 Appendix 1 Medical Emergency Planning Checklist (Updated regularly at www.brocku.ca/pandemicplan) 1. Store a supply of water and food. During a medical emergency like pandemic influenza, if you cannot get to a store, or if stores are out of supplies, it will be important for you to have extra supplies on hand. This can be useful in other types of emergencies, such as power outages and disasters. Calculate how much your family would need for two weeks and store separately from your regular food. Here are some suggestions to help you stock emergency supplies: Ready-to-eat canned meats, fruits vegetables, soups and fish Protein or fruit bars Dry cereal or granola Peanut butter or nuts Dried fruit Crackers Canned juices Bottled water (2 liters of water per person per day) Canned or jarred baby food and formula Pet food Skim milk powder and evaporated milk Prescribed medical supplies such as glucose and blood-pressure monitoring equipment Soap and water, or alcohol-based hand wash Medicines for fever, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen Thermometer Medication to prevent vomiting (e.g. Gravol) Anti-diarrheal medication (e.g. Imodium, PeptoBismol) Vitamins Fluids with electrolytes (e.g. Pedialyte, Sports Drinks) Cleansing agent/soap Flashlights Batteries Portable radio Manual can opener Garbage bags Tissues, toilet paper, disposable diapers 2. Ask your doctor and insurance company if you can get an extra supply of your regular prescription drugs. 24 3. Have any nonprescription drugs and other health supplies on hand, including pain relievers, stomach remedies, cough and cold medicines, fluids with electrolytes, and vitamins. 4. Talk with family members and loved ones about how they would be cared for if they got sick, or what will be needed to care for them in your home. 5. Volunteer with local groups to prepare and assist with emergency response. 6. Get involved in your community as it works to prepare for an influenza pandemic. 7. Make list of contact telephone numbers – work, public health, family. And once you have taken the time to prepare for a medical emergency, teach your children what to do, too! Appendix 2 25 Medical Emergency Planning Educational Information (Also found at www.brocku.ca/pandemicplan) TRUE FLU FACTS Influenza is serious, acute, respiratory illness that is caused by a virus. Symptoms may include sudden onset of fever, chills, cough, sore throat, headache, muscle aches, extreme weakness and fatigue. The cough and fatigue can persist for several weeks but usually illness lasts from two to seven days. Some will develop complications and require hospitalization. Every year the flu is responsible for up to 4500 deaths in Canada. Influenza is spread by respiratory droplets from infected persons through coughing, sneezing or talking. It is also spread through direct contact with surfaces contaminated by the virus, such as keyboards, eating utensils and unwashed hands. How Can I Avoid Catching The Flu? The best way to prevent the seasonal flu is to get a flu vaccination each fall. Avoid close contact with people who are sick. Stay at home when you are sick so you can help prevent others from catching your illness. Cover your mouth and nose with a tissue or sleeve when you cough or sneeze. Wash your hands often to get rid of the germs your hands collect. Avoid touching your eyes, nose or mouth, as this is how the influenza virus enters your body. To minimize your risk of catching the flu: Wash your hands after every activity. Think before you kiss. Cough or sneeze into your sleeve. Keep your hands to yourself. Stay home when you are sick. Keep your room clean!(door handles, light switches, keyboards, phones) Don’t share your drink with anyone. Don’t touch your face with your fingers. Wash your hands again! What About A Flu Shot? 26 Who: All residents of Ontario are encouraged to get the flu vaccine. It is provided free of charge by the Ontario government to anyone over age 6 months,. What: The influenza vaccine does not contain live virus so you cannot get the flu from the flu shot. Protection develops two weeks after receiving the vaccine and may last for one year. A new vaccine is prepared each year to provide immunity to the strains of flu expected for the upcoming season. Immunization is required each year. Where: Flu immunization is available from community clinics or your family doctor. Brock provides annual clinics for all students and employees. Students at Brock can receive a flu shot with an appointment at Student Health Services. ext. 3243 When: Immunization is recommended in October and November each year. In North America the peak flu season runs from November to March. What Can Be Done If I Catch The Flu? Since antibiotics are not effective for infections caused by a virus, there is no antibiotic treatment for the flu. There are some anti-viral medications, eg Tamiflu. They are best started within 48 hours of the onset of flu symptoms. Antiviral medication does not eliminate symptoms but can shorten the course of the illness. Keep well hydrated; clear fluids, including chicken soup and fruit juices, are good. Treat fever with ibuprofen or acetaminophen, not aspirin. Use Gravol for nausea and Imodium for diarrhea if needed. Is It A COLD Or Is It FLU? Signs & Symptoms COLD FLU 27 Fever, chills Low fever, if any Usual; can be a high fever Headache Rare Usual General aches and pains Mild, if any Usual; often severe; affect the body all over Fatigue and weakness Mild if any Usual, often severe Runny, stuffy nose Common Sometimes Sneezing Common Sometimes Sore throat Common Sometimes Cough Mild to moderate; hacking cough Common; can become severe Onset Gradual onset Usually starts with a scratchy throat and runny nose Sudden, usually starts with a fever, fatigue and general aches and pains Severity Minor infection of nose and throat More severe. Quite ill for 3-5 days but may not fully recover for days or weeks. may lead to pneumonia, bacterial infections or hospitalizations. If symptoms persist beyond two weeks. If you develop shortness of breath, painful breathing, earaches, pain around your eyes or cheekbones or a severe sore throat. If you seem to get better, then worse again. . When to see a Doctor