The Case for Vintage Electronic Drums by Michael Render You first

advertisement

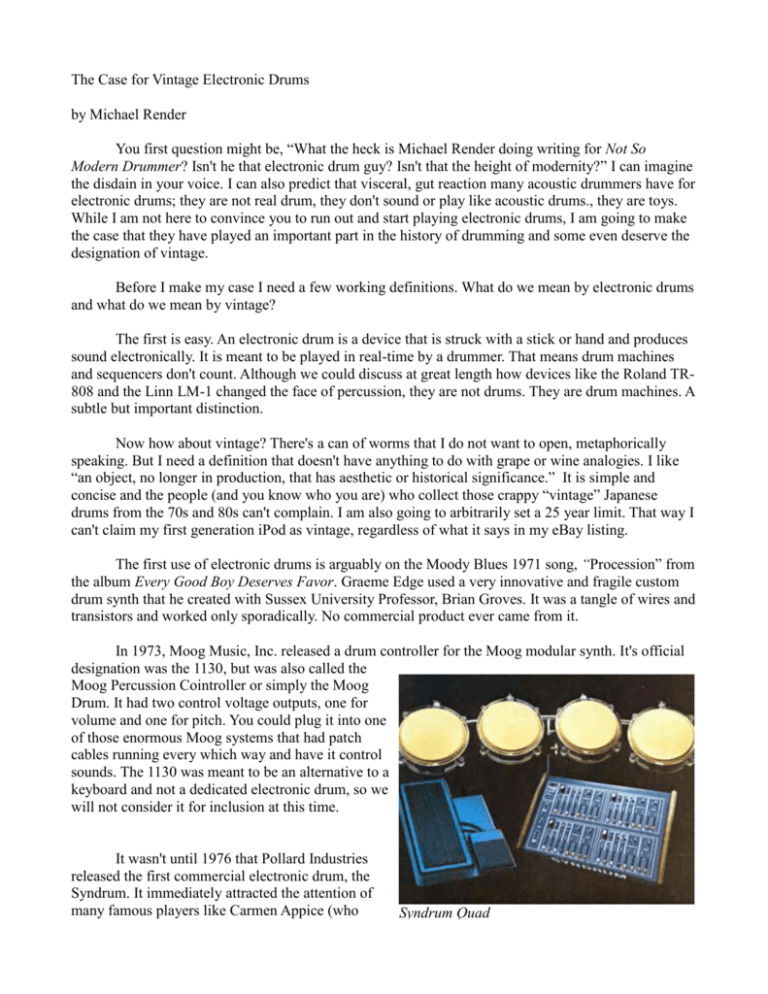

The Case for Vintage Electronic Drums by Michael Render You first question might be, “What the heck is Michael Render doing writing for Not So Modern Drummer? Isn't he that electronic drum guy? Isn't that the height of modernity?” I can imagine the disdain in your voice. I can also predict that visceral, gut reaction many acoustic drummers have for electronic drums; they are not real drum, they don't sound or play like acoustic drums., they are toys. While I am not here to convince you to run out and start playing electronic drums, I am going to make the case that they have played an important part in the history of drumming and some even deserve the designation of vintage. Before I make my case I need a few working definitions. What do we mean by electronic drums and what do we mean by vintage? The first is easy. An electronic drum is a device that is struck with a stick or hand and produces sound electronically. It is meant to be played in real-time by a drummer. That means drum machines and sequencers don't count. Although we could discuss at great length how devices like the Roland TR808 and the Linn LM-1 changed the face of percussion, they are not drums. They are drum machines. A subtle but important distinction. Now how about vintage? There's a can of worms that I do not want to open, metaphorically speaking. But I need a definition that doesn't have anything to do with grape or wine analogies. I like “an object, no longer in production, that has aesthetic or historical significance.” It is simple and concise and the people (and you know who you are) who collect those crappy “vintage” Japanese drums from the 70s and 80s can't complain. I am also going to arbitrarily set a 25 year limit. That way I can't claim my first generation iPod as vintage, regardless of what it says in my eBay listing. The first use of electronic drums is arguably on the Moody Blues 1971 song, “Procession” from the album Every Good Boy Deserves Favor. Graeme Edge used a very innovative and fragile custom drum synth that he created with Sussex University Professor, Brian Groves. It was a tangle of wires and transistors and worked only sporadically. No commercial product ever came from it. In 1973, Moog Music, Inc. released a drum controller for the Moog modular synth. It's official designation was the 1130, but was also called the Moog Percussion Cointroller or simply the Moog Drum. It had two control voltage outputs, one for volume and one for pitch. You could plug it into one of those enormous Moog systems that had patch cables running every which way and have it control sounds. The 1130 was meant to be an alternative to a keyboard and not a dedicated electronic drum, so we will not consider it for inclusion at this time. It wasn't until 1976 that Pollard Industries released the first commercial electronic drum, the Syndrum. It immediately attracted the attention of many famous players like Carmen Appice (who Syndrum Quad appeared in their ads), Terry Bozzio and, of course, Graeme Edge. Although not a financial success for Pollard Industries, the Syndrum did introduce the world to the sweeping “doooooom” sound that was to become a classic signature of electronic drums. That sound was soon to be heard on many recordings, from Linda Ronstadt's “Poor Pitiful Me” to Gerry Rafferty's “Baker Street” to The Car's “My Best Friend's Girlfriend.” The Syndrum consisted of a sound module and one or more external drum pads with Duraline Superheads. That's right, Kevlar heads! The available models were the Quad, the Twin and the Single. The only difference being the number of pads each unit could handle. There were no patches, no memory, just sliders and knobs. The manual even came with diagrams showing how to quickly achieve such standard sounds as Spacesound...Laser, Bird Call and Backwards Tom. A cheaper Syndrum called the CSM was also produced. It was an all-in-one unit that was less feature rich than the others and had the sound module in the same case as the pad. Syndrum CSM In 1977, Star Instruments introduced the Synare. Many people have confused the Syndrum with the Synare, but they were made by two distinct companies. Although they share the same basic concepts, the Synare added a few of it's own unique features, including a fully adjustable filter, ring modulator and pink noise. It quickly became a mainstay of the disco and early electronic crowd and can be heard on numerous recordings. The sound is so pervasive that Synare emulators for modern DAWs are popping up even today. The Synare models all had the pads built into the sound module. The Synare 1 had four pads, whereas the Synare 2 had 12. The Synare 2 Synare 1 was striving to be the percussion equivalent of a keyboard synthesizer and even included a sequencer. That is dangerously close to violating our definition of electronic drum, but it was meant to be played by a drummer with sticks, so it still fits. The Synare 3 was the affordable model, much like the Syndrum CSM. It was a single, UFO shaped pad with all the electronics inside. This is probably the model most people will recognize. The configurations of the Syndrum and Synare models seems to confirm the idea that they were originally intended as a supplement for acoustic kits, not as a replacement. And the recordings also bear this out. Electronic drums were used for emphasis and accent. Even with the incessant playing of the Synare on the first beat of every measure on Anita Baker's “Ring My Bell,” (ouch) there were still acoustic drums holding down the beat. Then along Came Simmons. S ynare 3 In 1978, the Simmons Company was create in Britain by Dave Simmons specifically to create an electronic drum set; something that could compete with acoustics sets using advanced electronic sound generation. The most notable of these were the SDS-V in 1981 and the SDS-7 in 1983. The SDS-V was hailed as “the world's first fully electronic drum set.” It was first heard on Spandau Ballet's 1981 hit, “Chant No. 1 (I Don't Need This Pressure On).” After that, it caught on with many 80s musicians and was featured by such bands as Duran Duran and Rush. It consisted of the now famous Hexagon pads and a modular, rack mount brain. The standard kit came with five modules, kick, snare and three toms. The were a few major drawbacks, though. The pads were very hard and caused wrist and elbow injury and the cymbal and hi-hat modules were universally decried as being “awful” or sounding like “trash can lids.” Still, the world was introduced to that distinctive Simmons “dzzshhh” sound and music was forever changed. Bill Bruford playing the SDS-V The SDS-7 was the first electronic drum to use digital samples. It used modules like the SDS-V, but each module had an EEPROM for 8-bit samples as well as an analog synth. The Hexagon pads were still around, but Simmons had started using a soft rubber for the striking surface, much to the relief of the electronic drum users. The SDS-7 also had memory for 99 patches and an optional EPROM burner to upload your own samples. Digital and analog had finally collided in the drum world. That is where we will stop in order to keep to our 25 year limit. The Tama Techstar and the Dynacord Percuter will have to wait till next year to be included in this list. Well, the history of electronic drums is all well and fine, but can these units be called vintage? The first criteria is easily met; they are all out of production. Heck, the companies that built them aren't even around anymore. As for historical significance, I would have to say that they all meet that criteria also. The Syndrum, Synare and Simmons drums all revolutionized the sound of drumming. They were as distinctive as a 24” Slingerland bass with calf skin heads. And they were the building blocks for today's modern electronic drums. I think the historical significance is pretty self-evident, but if you are really itching for a fight, give me call. I hate to judge aesthetics. It's such a personal thing. From a visual point of view, the distinctive looks of the Synare 3 and the Simmons Hexagon pads can be thought of as elegant design. The sound of these drums, however, is harder to rate. When we hear them now, we all immediately think “retro.” And so we should. But retro doesn't always mean bad. Sometimes it just means old, or vintage. I love the sound of a 1938 Slingerland set, but it sounds dated, old and vintage. Of course I have one more criteria for vintage. It may not be in the formal definition, but it is in the de facto definition. Does anybody value these electronic drums enough to buy them, collect them and write about them? Sure do. A quick glance around eBay will uncover tons of vintage electronic drums. Not surprisingly, Simmons drums are more popular than the others as they have had a longer production life and larger sales numbers. But every once in awhile an original Syndrum or Synare will pop up. The Synare 3 still fetches $250-$300 at auction. All that money for a device that goes “doooooom.” There are websites devoted to vintage electronic drums where they share information and pictures. And yes, there are people who own these units and won't give them up. They lovingly clean, restore and, most importantly, play these drums. I don't think there is any doubt that the Syndrum, Synare and Simmons drums can be classified as vintage. They meet all the criteria, both formal and de facto. They are pieces of our drumming history that remind us of where we came from and where we are going. There will always be drummers who don't care for electronics. But if we all liked the same thing, there would only be one drum set in the world. And we know that isn't going to happen anytime soon. Electronic drums can be vintage, and come to think of it, Not So Modern. Michael Render lives in Akron, OH and is a drummer, composer, author and software engineer - not necessarily in that order.