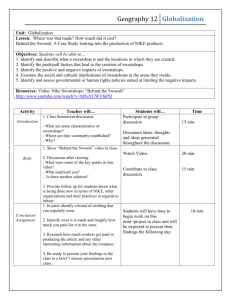

Is GSU Apparel Made in Sweatshops

advertisement