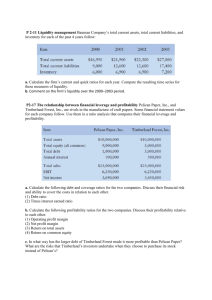

Handout #1 - Department of Agricultural Economics

advertisement

Handout #1

Agricultural Economics

489/689

Handout #1

Spring Semester 2008

John B. Penson, Jr.

2

Part I: Review of Concepts and Jargon

A. Introduction to Terminology

Before proceeding with key topics in the financial analysis of an agricultural firm, we

need to refresh your memory on key terminology and introduce you to others.

Liquidity

Liquidity is generally defined as the ability to generate cash quickly to meet claims on the

business without disrupting the ongoing operations of the business. There are three forms

of liquidity: (1) asset liquidity, (2) credit liquidity and (3) cash flow liquidity.

Asset liquidity – the ability to convert assets to cash quickly to meet claims on the

business without disrupting the ongoing operations of the business. If the firm can

convert its current assets to cash, retire its current liabilities and have cash left over, the

firm is said to be liquid. Assets that can be converted to cash quickly are referred to as

current assets, and include financial instruments (cash itself, stocks and bonds and

accounts and notes receivable) as well as non-financial assets like unsold production

inventories and inventories of purchased inputs. Assets on a firm’s balance sheet are

typically ordered in terms of their liquidity, which explains why cash appears first in the

asset column of the balance sheet and land appears last. While land may be sold quickly,

its sale will affect the ongoing nature of the firm’s business operations.

Credit liquidity – the ability to borrow cash quickly to meet claims on the

business without disrupting the ongoing operations of the business. This concept is

related to the firm’s unused credit reserves, or the maximum amount of credit lenders will

typically extend to a firm based upon its debt/equity structure.

Cash flow liquidity – the first two measures of liquidity are typically based upon

balance sheet evaluations at a specific point in time. Cash flow liquidity on the other

hand is a periodic measure of liquidity, usually monthly. The firm’s monthly cash flow

statement reflects the cash flows available and cash flows required during the month. If

the ensuing difference between these totals, or net cash balance, is positive, the firm is

liquid during that month.

Solvency

Solvency refers to the ability of the firm to convert all its assets to cash, retire all of its

liabilities and have cash left over. Note the emphasis on all assets and all liabilities as

3

opposed to current assets and current liabilities when we discussed the concept of asset

liquidity described above.

Profitability

Profitability refers to the ability of a firm to generate a level of revenue that exceeds its

total costs of production. The bottom line of the firm’s income statement reflects the net

income of the firm, one of many measures of profitability. Care must be taken when

assessing profitability over time to account for changes in the purchasing power of

money. Nominal net income refers to net income not been adjusted for inflation while

real net income reflects adjustments for changes in the purchasing power of the firm’s

profits from one year to the next.

Economic efficiency

Economic efficiency refers to the ability of the firm to use its resources to achieve a

desired result with little or no wasted effort or expense. This differs from technical

efficiency or productivity (i.e., yield per acre) which does not take prices or unit costs of

production into account.

Debt repayment capacity

Debt repayment capacity refers to the ability of the firm to meet its scheduled term debt

and capital lease payments and have cash left over. This concept is closely linked to the

concept of unused credit reserves in the literature, or the difference between the

maximum capacity to borrow as viewed by lenders and the amount of borrowed capital

the firm has already undertaken.

Present vs. future value

Present value refers to the value today of a sum of money or stream on payments to be

received in the future, discounted back to the present using an appropriate required rate of

return. Future value, on the other hand, refers to the value at a specific future date of a

sum of money or stream of payments (perhaps to an annuity).

Risk

The possible variation associated with the expected return or value measured by the

standard deviation or coefficient of variation. There are many forms of risk, including

price risk, interest rate risk, yield risk, political risk, relationship risk, etc.). This

collectively is often referred to as business risk, or the relative dispersion or variability in

4

the firm’s expected earnings. This differs then from financial risk, or the potential loss

in equity associated with the use of leverage (debt and equity capital). Finally, risk can

also be classified as systematic risk (or non-diversifiable risk) and unsystematic risk (the

portion of the variation in investment returns that cannot be eliminated by

diversification).

Physical vs. financial capital

Physical capital refers to those assets on the firm’s balance sheet that are not in the form

of financial instruments. Examples include inventories of unsold production, machinery

and equipment, inventories of production inputs, trucks, buildings and land. Financial

capital, on the other hand, typically refers to financial instruments (cash, stocks and

bonds) as well as the equity capital the owners firm have invested in the firm.

Explicit vs. implicit costs

Explicit costs are those expenses such as wages paid to hired labor where a cash payment

to others is required. Implicit costs on the other hand are those expenses such as

depreciation or opportunity costs that do not involve the payment of money.

Variable vs. fixed expenses

Variable expenses are those expenses that vary with the level of production. Fuel and

fertilizer expenses are two examples. Fixed expenses, on the other hand, are those

expenses that do not vary with the level of production. A property tax payment, which

must be paid even if output of the firm is zero, is a form of fixed expenses.

Optimal capital structure

This refers to the capital structure that maximizes the firm’s composite cost of capital for

a given amount of debt and equity capital. This will be influenced by the relative cost of

financing capital acquisition opportunities with debt and equity capital.

Capital budgeting

The decision making process associated with investment in fixed assets (machinery and

equipment, land and buildings. There are various forms of capital budgeting methods

available, including the payback period method, the profitability index method, the

internal rate of return method and the net present value method. Each will be covered in

depth later in this booklet.

5

Financial analysis

Financial analysis refers to the assessment of a firm’s financial performance, both from a

historical perspective and a futuristic perspective. The overall objective is to determine

the firm’s existing financial strengths and weaknesses, and to develop/evaluate strategies

that affect the firm’s future performance. Both perspectives involve the use of financial

ratios as performance indicators as well as decision aides or analytical tools to evaluate

decisions to expand/contract enterprises in the firm.

B. Key Financial Indicators to Track

Measures of liquidity

There are several approaches to measuring the liquidity of a firm depending on whether

you are talking about asset liquidity, credit liquidity or cash flow liquidity.

Two common measures of asset liquidity are the current ratio and the level of working

capital. The current ratio is given by:

(1)

Current ratio = current assets current liabilities

where current assets are those assets that can be converted to cash within the year and

current liabilities are those liabilities that are due within the year. If this ratio is greater

than 1.0, the firm is said to be liquid, or able to retire all its current liabilities with its

current assets and have cash left over. Studies have shown, however, that the firm can be

liquid and still fail. Other ratios (acid test ratio and cash ratio) represent variations of

equation (1), where specific categories of current assets are excluded from the numerator.

The level of working capital is given by:

(2)

working capital = current assets – current liabilities

If the level of working capital is positive, then the firm has sufficient current assets to

cover all its current liabilities and still have cash left over. This term is sometimes

referred to as net working capital.

Measures of solvency

There are numerous approaches to measuring the solvency of the firm. They all involve

balance sheet data and are transformations of one another. These measures include the

6

debt ratio, the net worth ratio, the asset ratio and the leverage ratio. Each is defined as

follows:

(3)

debt ratio = total debt or liabilities total assets

(4)

net worth ratio = total net worth or equity total assets

(5)

asset ratio = total assets total debt or liabilities

(6)

leverage ratio = total debt or liabilities total net worth or equity

Suppose the firm’s total assets are $100 and its total debt or liabilities are $25. In this

case the firm’s debt ratio would be 0.25, its net worth ratio would be 0.75, its asset ratio

would be 4.0, and its leverage ratio would be 0.33. All ratios indicate this firm would be

solvent; its could convert all of its assets ($100) to cash, retire all of its liabilities ($25),

and still have cash left over ($75).

Measures of profitability

In addition to the level of net income, which we said earlier is a measure of profitability,

other commonly-used measures exist. These include the rate of return on assets (ROA)

and the rate of return on equity capital (ROE). Another measure is the net or operating

profit margin. These measures can be defined as follows:

(7)

Rate of return on assets = (net income + interest expense) total assets

(8)

Rate of return on equity = net income total equity or net worth

(9)

Net profit margin = (EBIT – tax) total revenue

where EBIT represents earnings before interest and tax payments, or net income minus

interest and tax payments. Suppose a firm had the following characteristics: $100 in total

assets, $25 in total debt, total revenue of $200, interest expenses of $5, taxes of $10 and

other expenses totaling $130. The firm’s net income would be $55 (i.e., $200 - $130 $5 - $10) and its EBIT would be $70 (i.e., $55 + $5 +$10). This would result in a ROA

of 60% (i.e., {[$55 + $5]$100}100); an ROE of 73% (i.e., [$55$75] 100), and a net

profit margin of 30% (i.e., {[$70 - $10] $200} 100).

Measures of economic efficiency

Like the other financial indicators, there are a variety of measures of economic efficiency

used by financial analysts. These include a number of expense ratios (interest expense

ratio, variable expense ratio, depreciation expense ratio) as well as several turnover ratios

(total asset turnover and fixed asset turnover). These ratios are defined as follows:

7

(10)

interest expense ratio = interest expenses total revenue

(11)

variable expense ratio = total variable expenses total revenue

(12)

depreciation expense ratio = depreciation expenses total revenue

(13)

total asset turnover ratio = total revenue total assets

(14)

fixed asset turnover ratio = total revenue fixed assets

Assume the firm’s depreciation expense is $20 and its total fixed assets are $85. Using

the example discussed with respect to measures of profitability, the firm’s interest

expense ratio would be 2.5% (i.e., [$5$200] 100), its variable expense ratio would be

55% (i.e., {[$130 - $20] $200}100), its depreciation expense ratio would be 10% (i.e.,

[$20$200] 100), its total asset turnover ratio would be 2.0 (i.e., $200$100) and its

fixed asset turnover ratio would be 2.35 (i.e., $200$100). This means the firm’s interest

expenses, variable expenses and depreciation expenses are 2.5%, 55% and 10% of every

dollar of total revenue, respectively. The firm furthermore turns over its total assets twice

each year and fixed assets 2.35 times each year.

Measures of debt repayment capacity

Finally, measures of debt repayment capacity include term debt and capital lease

coverage ratio, times interest earned ratio, and debt burden ratio to name a few. They are

calculated as follows:

(15)

Term debt and capital

lease coverage ratio = (EBIT – taxes) term debt and capital lease payments

(16)

Times interest earned ratio = (EBIT – taxes) scheduled interest payments

(17)

Debt burden ratio = total debt outstanding net income

The financial indicators in equations (15) and (16) should be greater than one. This

would indicate the firm has, at minimum, the capability to service their commitments as

scheduled. Obviously the greater these ratios are, the greater the comfort zone for the

lender. Equation (17) indicated the number of periods needed to retire total debt

outstanding if net income was used entirely for this purpose. If the net income statistic

used comes from an annual income statement, then this ratio would reflect the number of

years necessary to retire the firm’s entire debt. While this may reflect the eventual

application of net income, it does indicate to a lender the firm’s ability to retire debt from

operations.

8

C. Financial Strength and Performance of the Firm

Financial analysis was defined earlier as “the assessment of a firm’s financial condition

or well being”. Its objectives were said to be “determine the firm’s financial strengths

and identify its weaknesses”. A number of financial indicators were defined and

interpreted. Nothing however was said about the basis for comparison other than a

specific level so satisfy the definition of liquidity, etc.

Often the most accurate or reveling assessment of a firm’s financial strength and

performance involves assessing the trends in a number of ratios over time and deviations

from the financial achievements of other similar or “like kind” firms. This is called

historical financial analysis and comparative financial analysis.

Historical analysis

Historical financial analysis involves comparing the firm’s current performance with its

performance in previous years, and identifying the underlying reasons for deviations from

expectations. This involves computing the above measures for liquidity, solvency,

profitability, economic efficiency and debt repayment capacity (one measure from each

group should do) for the latest available year (2000) and comparing the values of each

measure with say the Olympic average over the last five years (drop the high and low

when computing the average).

Understanding why any undesirable deviations in liquidity, solvency, profitability and

other categories of financial indicators occurred during the most recent period may help

formulate strategies that prevent further occurrences. There may very well be a good

explanation tied to one-time events beyond the control of the producer. Conducting a

comparative financial analysis with similar firms will help confirm this conclusion

Comparative analysis

As the name suggests, comparative financial analysis involves comparing the financial

strength and performance of the firm with that of similar firms. The current weak

performance of the firm may not be a one-time event beyond the control of the producer,

but rather something similar firms did not experience, at least not to the same degree.1

A study by W. H. Beavers showed that the financial ratios of firms that subsequently fail

are different from those firms that survived.2 Beavers tracked the current ratio, debt ratio,

References to similar or “like kind” firms refers to comparisons with firms of similar size producing the

same products in the same geographical area for the same market structure.

2

W. H. Beavers, “Financial Ratios and Predictors of Failure”, in Empirical Research in Accounting:

Selected Studies, Supplement to Journal of Accounting Research, Volume 66:77-111.

1

9

rate of return on assets, and the reciprocal of the debt burden ratio described earlier in this

booklet (equations (1), (3), (7) and (17) respectively).

Catching undesirable differences from other firms in its peer group early enough to

minimize or eliminate their long-term effects is paramount to the long run success of the

firm. The gap between the successful firms and the firms that failed in the Beavers study

was not that great in the initial year. The growth in the use of borrowed funds to cash

flow operations in subsequent years, however, eventually led to sharp differences

between the successful and failing firms as additional interest expenses grew and ROA

declined.

Summary

The bottom line is that completion of financial statements to meet external reporting

requirements only to then store them in a filing cabinet ignores a rich source of

information on assessing the financial health of the business. Furthermore, calculation of

the various measures described in equations (1) thru (17) in the previous section of this

booklet does not necessarily help matters much. The issue is whether or not the firm’s

performance improved over last year’s results or the Olympic average over the last 5

years. And if not, why? This requires the use of historical financial analysis. In

addition, comparative financial analysis can tell us whether a down trend in these various

performance indicators is something unique to the firm, or is being experienced by other

“like kind” firms as well.