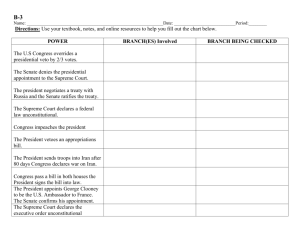

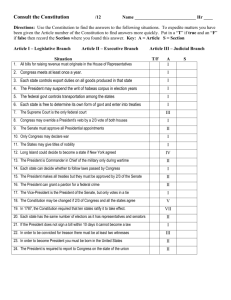

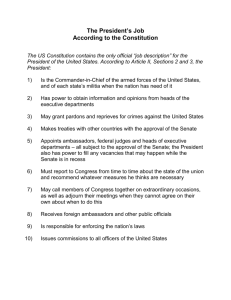

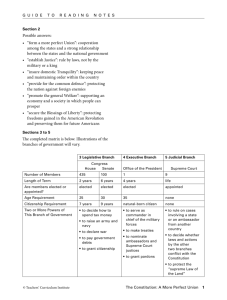

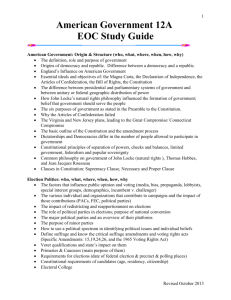

chapter one:constitutional underpinnings

advertisement