1 Executive Summary

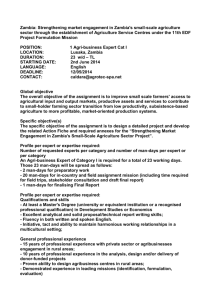

advertisement