Briefing Paper PA 762

advertisement

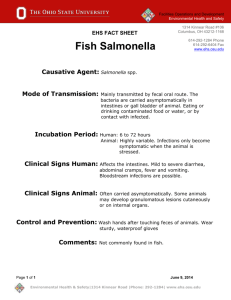

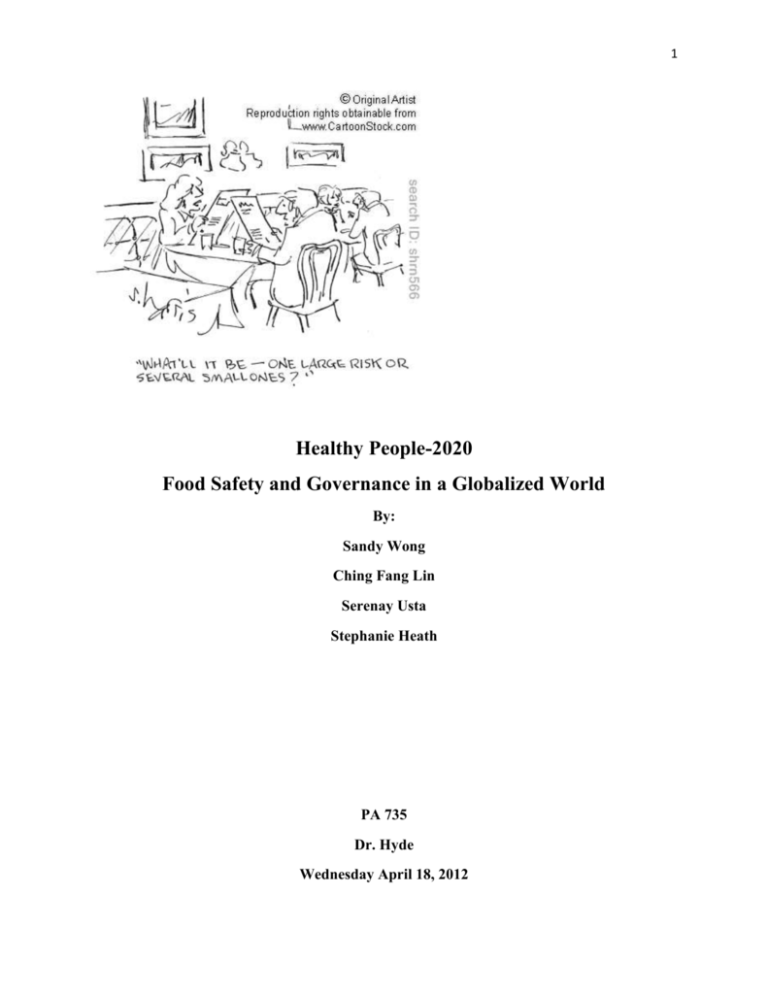

1 Healthy People-2020 Food Safety and Governance in a Globalized World By: Sandy Wong Ching Fang Lin Serenay Usta Stephanie Heath PA 735 Dr. Hyde Wednesday April 18, 2012 2 Introduction and Context With rising consumer concerns, food safety is an important public health issue for governments around the world. Estimated by World Health Organization (WHO), the average of people died because of unsafe food and water every year in the world is 2.2 million and among them, 1.9 million are children (WHO, 2012). Food safety is an important public health problem for United States as well. According to the FoodNet annual report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the foodborne illness outbreak caused by E. coli infections has declined almost 50% during the past 15 years; however, the Salmonella infections has not reduced significantly during the same time (Figure 1). Based on the estimation of CDC, the Salmonella infections result most hospitalizations and deaths each year. Showed in Figure 2, the annual economic cost of the Salmonella infections is approximately 2.7 billion (USDA, 2011). While the illness of dangerous type of E. coli can be cut by half, why the same quantity of people still get sick because of Salmonella as fifteen years ago? How can or why can’t we apply lessons learned from E. coli to reduce the infections caused by Salmonella? Such questions present the significance of food safety issue in the United States (CDC, 2011). As a result of globalization of trade in food, the issue of food safety has become more complex. Globalization is an ongoing and accelerating process that results in global economic, political, cultural and environmental interconnections among people, corporations and countries (Steger, 2010). Accordingly, public health in the United States is increasing threatened by the food safety incidences emerged in other countries. While globalization makes the borders of political boundaries irrelevant in the food safety issues, it is placing immense pressures on national governments to integrate and collaborate within a global economic system (Lin, 2011). 3 To effectively accomplish these benchmarks, HHS in the leading position to tackle the food safety issue increasingly relies on collaborative governance which governments, NGOs and companies at local, national and international levels (Figure3) together to engage in “consensusoriented decision making” regarding the food safety issue (Ansell &Gash, 2007). The Big Question Despite the warnings, knowledge and news stories about food borne illnesses such as salmonella, listeria, vibrio and most recently the “pink slime” epidemic, these types of illness is still a highly significant source of human disease. New food safety messages to consumers on a global level will prove to create a more successful relay of information which will hopefully make for more sincere consumers and less food borne illnesses and even deaths. But how do we make these messages reach all areas of the globe? Most importantly, how do we make food safe for everyone on a global scale? In figure 5, are recommendations to achieve food safety. Narrowing down who is in charge of food processing, consumption and relaying the messages to the consumer is the most relevant piece of information when answering these types of questions. Is it farmers and small agricultural business owners; is it the public sector or the private sector? According to an article from Agriculture and Human Values, experts have identified that there are issues from water quality to personal hygiene that are critical areas of food safety that if handled correctly could decrease the risk associated with food borne illnesses. How do we get all farmers to follow these types of practices where food safety is concerned? By forcing farmers and those in charge of food production into practicing safer procedures that are most likely more time consuming the price of healthier food will rise which will put consumers who can’t afford certain types of food into purchasing unhealthy food or chemically enhanced 4 food and how do we know if that is any better? How to grow and create (non-chemically) and ensure food that is healthy, fresh and pure for all consumers is the big question at hand. Driving Forces Challenges of driving forces assessed by all stakeholders in sustaining food safety emerge from economic, demographic, cultural, and social dimensions. Figure 1 summarizes how global trends frame forces that are affecting policy outcomes and management strategies. Cultural differences reflect variety of perceptions and preferences of communities regarding food selection. Its main implication is creation of different safety considerations affecting food trade globally. Producers are required to meet cultural expectations. Administrative and political component of the diagram points to differences among food safety regulations. Parallel to cultural differences of societies, governments may have different attitudes towards food safety. It leads different policies and measures taken by governments that sustain food safety considerations. As a result, International Food Health Organizations tend to streamline this variety of regulations to maintain a global food standard. From the geographical perspective, environmental conditions of each country propose a challenge for food producers. Climate changes, pollution, farmers’ choice of pesticides, chemical contaminants, diversity of food preservation ways, and access to overseas are some of the challenges food health industry should be dealing with. Ultimately, these affect product features. Agriculture and livestock industries have to comply with global environmental changes as well as they have to meet a certain level of production to make profit while meeting consumer demands. Lastly, economic determinant of the diagram shows that economic development of countries may result in their varying level of strength in prioritizing food safety in their policies. For example, government financial capability can enhance its inspections regarding customs 5 control and food sampling at borders. Or, governments could incentivize producers to use healthy and qualified methods. Likewise, consumers’ personal income level can change their actions to allocate necessary care for their foods. All these four components are interrelated with a collaborated governance strategy that is recommended in Figure 4. Questions for the Future With the constant advancement of science, food is being genetically modified to be more sustainable to different elements. Due to genetically modified foods, more food is available to meet humanities demands. However, this advancement in food science can create issues in the future. With abundance of food, it can lead humanity to over consume; over consumption can cause health problems such as obesity and diabetes. Furthermore, there are limited amounts of scientific evidences to prove that genetically modified foods do not inflict harm to the human body. This raises the question to whether genetically modifying foods for quality and quantity will do more harm than benefits to humanity; will it create more issues in the long run? Moreover, if proven that genetically modified foods are harming humans, how will the government handle the backlash? The luxury of enjoying foods from all over the world also comes with downfalls. Different countries have different regulations; and these regulations might not necessarily meet the safety standards of other countries. Other than regulations, other issues such as corruption can also jeopardize the level of safety in a product. When faced with situations such as these, how can countries with higher standards (i.e., United States and Canada) assure the safety of imported foods for the people of their own country? Perhaps universal guidelines can be created for all counties to follow; but who will oversee the countries actions and to assure that they are 6 following guidelines? More importantly, how do we assure all countries, which operate independently, continue to follow the guidelines to food safety? References Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of public administration research & theory, 18(4), 543-571 Ghemawat, P. (2001). Distance Still Matters: The Hard Reality of Global Expansion. Harvard Business Review. Lin, C. (2011). Global food safety: Exploring key elements for an international regulatory strategy. Virginia journal of international law, 51 (3), 637-695. Parker, S et. al. (2012). Including growers in the food safety conversation: enhancing the design and implementation of food safety programming based in farm and marketing needs of fresh fruit and vegetable producers. Agriculture and Human Values DOI: 10.1007/s10460-012-9360-3 Steger, M. (2010). Globalization. a Brief Insight: Sterling Publishing Co, Inc.: New York The Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (2011), Trends in foodborne illness, 1996–2010. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/PDFs/FACTSHEET_B_TRENDS.PDF US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (2010), Foodborne illness cost calculator: Salmonella [Data file], Retrieved from 7 http://www.ers.usda.gov/data/FoodBorneIllness/salmPie.asp?Pathogen=Salmonella&p=1 &s=28 7&y=2010&n=2794374 World Health Organization (2012). Food safety [ WWW page]. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/index.html Figure1 Source: The Centers of Disease Control and Prevention 8 Figure2 Source: USDA/ Economic Research Service Figure3 Government Matrix Supranational Private Governmental Global & transnational food World Health Organizations companies; Media Third Sector International food safety advocacy NGOs ie. Safe Food International ie. Coco Cola 9 National Domestic food companies Federal agencies ie. Dole Health People 2020 Domestic public health advocacy NGOs ie. National Environmental Health Association Subnational Local business State & local governments ie. local grocery, famers -departments of public markets health State & local NGOs ie. UC Davis Center for Consumer Research CAGE Framework Figure 4 Attributes creating distance Cultural Administrative and Political Geographic Economic Different cultural perceptions and preferences on food Differences among food safety regulations Climateenvironmental conditions Country Development Choice of pesticides Industries effected by distance Food Trade Between Countries Producer Policies and measures taken by Governments that sustain food safety considerations International Food Health Organizations Agriculture and livestock Product Features Average Personal Income Governmental strength to prioritize food safety Consumers’ demand for food safety 10 Figure 5 Resources Collaboration Leadership Metrics Education Government assistant programs (i.e., WIC and food stamps) Subsidizing farmers Using different agencies to educate the public on food safety Government, school department, non-profit, and media Holding producers accountable: Food and Drug Administration United States Department of Agriculture Centers of Disease Control National Food Committee: Oversee strict food regulations Create food with tags that indicate safety information of product Assuring all departments are meeting the goals to food safety Using the number of food-borne illnesses before and after implanting changes 11