New York to Chicago

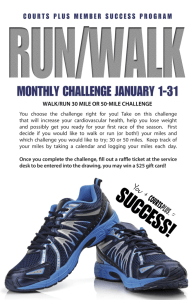

advertisement