Collected Essays

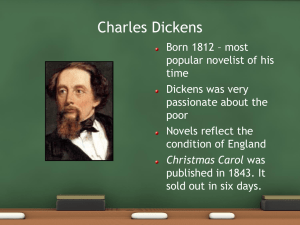

advertisement