Guide to Hybrid Securities

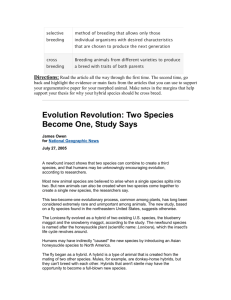

advertisement