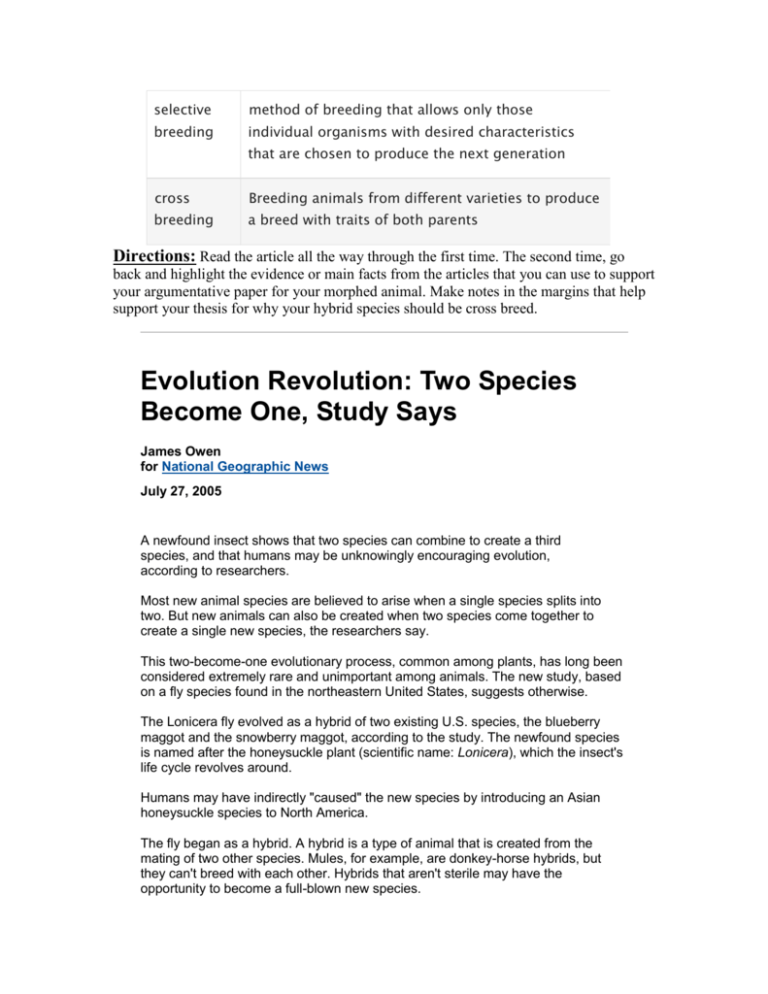

selective

method of breeding that allows only those

breeding

individual organisms with desired characteristics

that are chosen to produce the next generation

cross

Breeding animals from different varieties to produce

breeding

a breed with traits of both parents

Directions: Read the article all the way through the first time. The second time, go

back and highlight the evidence or main facts from the articles that you can use to support

your argumentative paper for your morphed animal. Make notes in the margins that help

support your thesis for why your hybrid species should be cross breed.

Evolution Revolution: Two Species

Become One, Study Says

James Owen

for National Geographic News

July 27, 2005

A newfound insect shows that two species can combine to create a third

species, and that humans may be unknowingly encouraging evolution,

according to researchers.

Most new animal species are believed to arise when a single species splits into

two. But new animals can also be created when two species come together to

create a single new species, the researchers say.

This two-become-one evolutionary process, common among plants, has long been

considered extremely rare and unimportant among animals. The new study, based

on a fly species found in the northeastern United States, suggests otherwise.

The Lonicera fly evolved as a hybrid of two existing U.S. species, the blueberry

maggot and the snowberry maggot, according to the study. The newfound species

is named after the honeysuckle plant (scientific name: Lonicera), which the insect's

life cycle revolves around.

Humans may have indirectly "caused" the new species by introducing an Asian

honeysuckle species to North America.

The fly began as a hybrid. A hybrid is a type of animal that is created from the

mating of two other species. Mules, for example, are donkey-horse hybrids, but

they can't breed with each other. Hybrids that aren't sterile may have the

opportunity to become a full-blown new species.

For this to happen, the hybrid requires a distinct niche where it can evolve

separately from its two parent species. For the Lonicera fly, the alien honeysuckle

plant provided that niche.

As a result, the fly provides the first evidence that two different animal species can

interbreed and evolve into a new, distinct animal if their hybrid moves to a new

habitat, the study suggests.

Conducted by researchers from Pennsylvania State University's entomology

department, the study will be reported tomorrow in the journal Nature.

DNA Analysis

The team established the insect's hybrid origins through detailed DNA

"fingerprinting" techniques.

Many other animals, particularly parasitic insects whose life cycles depend on a

particular host plant, may also have arisen through hybridization, says the study's

lead author, evolutionary ecologist Dietmar Schwarz. The difficulty, he says, is in

detecting this method of evolution.

"The problem is detection, which requires extensive genetic studies," Schwarz said.

"In animals there has been so far only limited information on this mode of

speciation."

George Turner is a professor of evolutionary biology and biodiversity at the

University of Hull in England. He agrees that animal evolution through hybridization

may be much more widespread than previously believed.

As DNA analysis of different species becomes more sophisticated and extensive,

he expects other examples to emerge.

"I think this kind of speciation is most likely in animals were there are lots of similar,

fast-evolving species, such as in certain types of insects and fish," he added.

Fish Hybrids

Turner says recent evidence indicates that some fish species also evolved as

hybrids.

German researchers have studied cichlids (a type of tropical freshwater fish) living

in tiny volcano-crater lakes in Cameroon, West Africa. Their studies have shown

that at least one cichlid species started off as a hybrid.

Among cichlids this process likely takes thousands of years. The Lonicera fly's

evolution, however, has occurred only in the 250 years since its honeysuckle host

plant arrived in North America.

The introduction, via humans, of non-native species makes speciation through

hybridization more likely, says Schwarz, the Penn State ecologist.

"On the one hand, introduced organisms provide new habitats," he said. "On the

other, one could imagine that introducing a parasite that is closely related to a

native species could lead to hybridization and, as a consequence, to the formation

of new [species] that might be able to utilize a previously unused host."

"Evolution hasn't ended," George Turner added. "New species are evolving, and

humans can have a big influence on that process."

Free E-Mail News Updates

Sign up for our Inside National Geographic newsletter. Every two weeks we'll send

you our top stories and pictures (see sample).

© 1996-2008 National Geographic Society. All rights reserved.